The Riddle of Penncroft Farm (10 page)

Read The Riddle of Penncroft Farm Online

Authors: Dorothea Jensen

Â

Â

Â

8

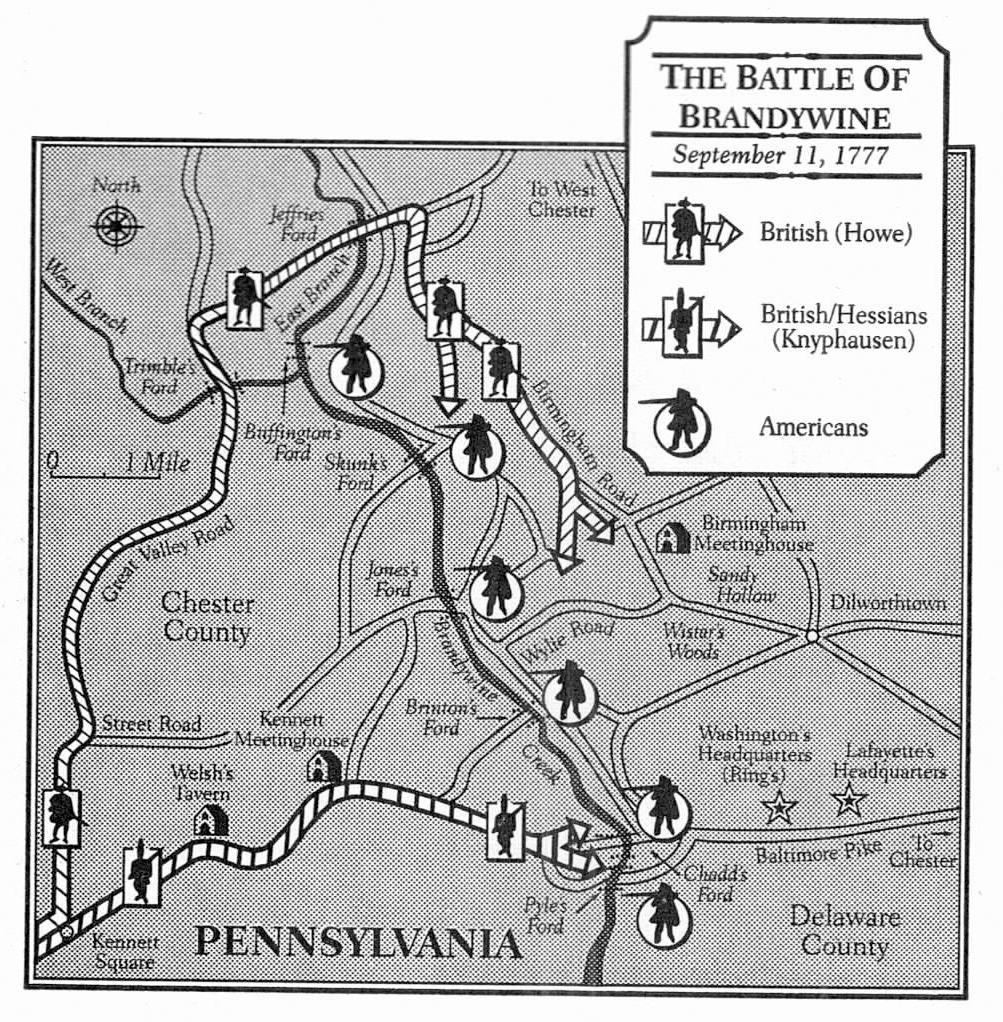

As it turned out, Squire Cheyney and I didn't get far before the road along the creek grew too crowded with American troops for our wagon to pass. Nothing daunted, Cheyney said we must leave the wagon on Wylie Road and ride the three miles overland to Ring's house, Washington's headquarters near Chadd's Ford. With growing misgivings, I helped unhitch the team and conceal the wagon in the woods, and soon we were up on Daisy's and Buttercup's bare backs, trotting over the rough ground. I clutched Buttercup's reins and mane for dear life as I followed Squire Cheyney up and down the steep wooded hills, more than once nearly sliding backward off Buttercup's rump or forward over his head. Cheyney, all unheeding, allowed branches to whip behind him into my face; they stung like the very devil

.

As we came out of the trees on the hill behind Ring's house and paused to get our bearings, I quickly forgot my stinging face, for I could hear the sharp staccato of musketry coming from Brandywine Creek below. The thought that Will might be the target made me sick with fear

.

Cheyney glanced at me. “Never heard muskets before, boy?” he asked brusquely, gathering up his reins

.

I shuddered. “Not trained on men. And not when one of those men might be my brother, and he could be shot from the back

.”

“

We'll prevent that if we get through in time! And Ring's is just below!” the squire cried, goading the winded Daisy into a gallop down the hill

. As

we reached the stone wall behind Washington's headquarters, a line of Continentals blocked our way. One grabbed Daisy's bridle and barked, “Don't you know there's a battle brewing? This is no place for farmers!

”

“

Don't be daft, sir!” Cheyney roared. “We've a pass from Sullivan to deliver urgent information to General Washington

.”

He held out a piece of paper. After the guard read it, he quickly motioned us on. Cheyney chirruped his horse down the hill, with mine wheezing along behind. We stopped beside the well. Dismounting, the squire sprinted around the side of the house and I scuttled behind him to the wide front door

.

Two brawny sentries brought us both to a halt. Squire Cheyney, glaring at them, simply hallooed through the doorway in a voice Knyphausen likely could hear above the booming cannon beyond the Brandywine. I caught my breath, not only because my brother's life hung in the balance, but also because I was to see the man many revered as a godâand my father reviled as the devil

.

My suspense lasted but a trice. A dignified figure in a buff-and-blue uniform appeared before usâGeneral Washington

.

Broad-shouldered, taller than anyone I'd ever seen, he regarded us through icy blue eyes. “There had better be an excellent reason for this interruption, sir,” he exclaimed

.

After all his sprinting and bellowing, Cheyney had little breath for speech. He panted like a landed fish for several long moments. Then, finally, he gasped out, “'Tis the British, ten thousand strong, crossing upstream to attack from behind

.”

Washington narrowed his eyes, looked us over as if we stank of barn muck, and motioned us into the house

.

“

I heard some such nonsense from Colonel Bland, but later reports proved this false,” he said, frowning. “Local sources have assured me there is no ford above the fork that's close enough to offer a serious threat. No, it's here at Chadd's Ford that the British attack will come, and here at the Brandywine is where we'll hold them!” In an undertone, he added, “Indeed we must: No other obstacles lie 'twixt Howe and Philadelphia save the Schuylkill Riverâat the very doors of the city!

”

The squire could barely contain his outrage. “Local sources be damned!” he spluttered. “I

am

a local source. And a local source most loyal to your efforts! Don't you know that most of the farmers who've stayed nearby, in

Howe's

path, are neutrals or Tories who want to throw dust in your eyes?” His voice squeaked with fury, and with despair I perceived that he sounded too much like a bedlamite to be taken seriously

.

Washington dismissed Cheyney's words with a wave of his hand. “And why should I not think

you

are doing the same? Nay, I choose to believe the word of an innocent youth before that of a man puffed full of Tory guile!

”

“

Tory guile?!” Cheyney squawked, as ruffled as a fighting cock

.

“

Yes, an innocent such as this lad here

.”

Suddenly I felt pride and glory swelling within me. As puffed up as any guileful man, I stepped forward and gazed up expectantly at that lofty, grave countenance

.

“

Aye, this lad,” repeated Washington. “Now confound the boy, where'd he get to? . . . NedâNed Owens?

”

“

Here, Excellency.” As we stood in the corridor, I could see a pudgy boy standing at a sideboard in the room to the right. In one hand he held a meat pasty; in the other, a pewter tankard. Juice from one or the other was dribbling down his cheeks. Crestfallen, I watched him wipe his mouth on his sleeve

.

“

Have you heard what this man says, Owens?

”

“

Aye, sir. And it be lies. I've been up and down the Brandywineâall the way north to the forkâand there's nary a ford you've not covered with patrols.” He leveled a look at me that was brimming over with self-importance. 'Twas this barefaced conceit that gave me back my tongue

.

“

But the British crossed

above

the fork, at

Jeffries'

Ford!” I exclaimed. “The squire saw them, and I

know

him to be true to the patriot cause. Redcoats in the

thousands

will be coming south down Birmingham Road, behind you to the east! Don't let

them flank your troops, sir. My brother, Will, is a Continental, and I couldn't bear

. . .”

I shall never know whyâ'twas probably a storm of nerves after all I'd been through and my fears for Willâbut then and there I burst into tears. No man would have done so, but 'tis likely my sobs did more than any man's vows (and surely more than Cheyney's dismayed howls) to convince Washington of the truth

.

For a long moment those cool blue eyes took my measure. Just then an aide dashed into the room and thrust some papers into Washington's hand. From what he said, it appeared they were reports verifying all that Squire Cheyney and I had told the general. Washington immediately ordered word sent to Sullivan to meet the column advancing on his rear. After the aide's departure, the general buckled on his sword. As he did so, he asked, “What's your name, lad?

”

“

Geordie

.”

“

We need drummer boys, Geordie. Join us, as Owens here has done.” He threw these words over his shoulder as he strode from the room. Jealously, I glanced at Owens. How much I wanted to take up the drumâand how impossible that I do so!

Squire Cheyney cleared his throat. “Well done, Geordie.” He mopped his brow with a handkerchief. “We'd best head back north to Wylie Road. 'Twill be

safe enoughâthe main battle will surely be to the east, where the redcoats are

.”

We hurried outside, but before we could mount, one of Washington's aides sped up the path and stopped the squire

.

“

Go along with the courier and show Sullivan the way to Birmingham Road!” He cast a disparaging look at Daisy. “That nag will not be quick enough. Come, I'll find another for you

.”

Squire Cheyney handed me Daisy's reins with a warning to waste no time, then rushed away with the aide. By this time the gunfire was quickening, making Buttercup as skittish as an unbroken filly. I was still trying to get up on her when General Washington himself emerged from the house, calling for a guide to lead him to Birmingham Road

.

I half hoped and half feared that I would be that guide, but instead his aides brought up an elderly man from the neighborhood, Mr. Joseph Brown. Old Mr. Brown made every possible excuse not to go, but in the end was convinced at swordpoint where his duty lay. When he protested his lack of a horse, one of Washington's aides dismounted from his own fine charger

.

As Brown reluctantly climbed into the saddle, Washington sat impatiently on his own beautiful

white horse. The instant the frightened farmer was in place, Washington snapped a whip at the rump of the reluctant guide's horse, which leaped into a gallop. The general followed, spurring his own mount until its nose pushed into the leader's flank like a colt suckling its mother. Even this didn't satisfy Washington, who cracked his whip and shouted, “Push along, old man, push along!” Spellbound, I watched the two race up the hill across the golden fields, jumping the fences as they came to them. I had never seen such horsemanshipâsuperb on the part of the general, dreadful on the part of Mr. Brown. Behind them ran a ragged line of soldiers, rucksacks bobbing as they sped over the uneven ground

.

After the two mismatched leaders disappeared over the brow of the hill, I managed to get on Buttercup and take hold of Daisy's bridle. It took very little urging to hasten the two frightened horses north, away from the sound of gunfire. By the time I got back to my wagon, my hands were too shaky for my fingers to work properly, and it took ages to harness the team. At the very moment I climbed to the seat and took up the reins, the valley behind me exploded with artillery fire. Terrified, Daisy and Buttercup reared in their traces. Up and up they went, pawing the smoke-filled air. Then they plunged back to the

ground, landing at a dead run. For a few breathless moments I simply clung to the reins, pulling for all I was worth, but the horses were too panic-stricken to feel the bits sawing at their mouths. My arms ached from the effort, and I eased off to recover some strength for another try

. Perhaps my horses bolting might be a blessing in disguise,

I thought. It would surely get me away from the Brandywine much faster than their usual pace. Then I realized where we were headed: due east toward Birmingham Road, where the British and Americans were about to clash in battle

.

With strength born of fear, I reached for the brake, only to have the lever break off in my hand. Clutching the reins, I shut my eyes and prayed. At the sound of gunfire, my eyes flew open once more. Up the hill to my left were two lines of soldiers. At the top of the ridge, one line raised their muskets in unconscious mimicry of the toy soldier in my pocket. Their tall caps were as pointed as my little grenadier's, their tunics as scarlet. But my toy had never spat forth puffs of smoke or blazes of fire as did the muzzles glinting in the sun. My eyes shifted down to the target below: the second line of soldiers, whose black cockaded hats proclaimed them Continentals. Under my horrified gaze, this American line wavered

and broke, some few soldiers staying to return fire, but most wheeling in confusion toward the road down which my team was bolting

.

As the wagon careened down the dusty lane, I glimpsed still, crumpled figures, their coats turning red with blood, lying in the field where the American line had stood. The thought that Will might be bleeding to death under the hot September sun made me steer my winded team into a thick copse of beech trees to consider what to do. 'Twas lucky I did, else I'd never have heard itâthe faint but unmistakable sound of Will's whistle. I shook my head, thinking I must be imagining things. Then it came again more clearly from the thicket ahead

.

I shot off the wagon seat and hurtled into the woods, crashing through underbrush in the manner of an animal fleeing a forest fire. My lips puckered soundlessly in the vain effort to whistle back. “Will! Where are you?” I finally called hoarsely

.

Through the leaves, a gleam of pallid skin told me I'd found him. Will lay at the base of a beech tree looking much as he did napping in our orchard after a dip in our pond on a hot summer day. But the dark red daubs on his leg came from no pond

.

“

Geordie! I thought my eyes were playing tricks on me, seeing you pull up in our wagon. But when I

whistled and you looked startled as a deer, I knew 'twas really you. Trust you to be in Wistar's Woods just when things got hot.” Managing a feeble grin, he tried to sit up. Then his face contorted with pain, and he fell back with a groan that tore at my heart

.

“

Don't you worry, Will,” I said with a confidence I was far from feeling. “I'm taking you home

.”

“

Nay,” Will said weakly. “If the lobsterbacks catch you

. . .”