The River of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History of Burma

Read The River of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History of Burma Online

Authors: Thant Myint-U

THE RIVER OF LOST FOOTSTEPS

A PERSONAL HISTORY OF BURMA

THANT MYINT-U

To my son, Thurayn-Harri

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

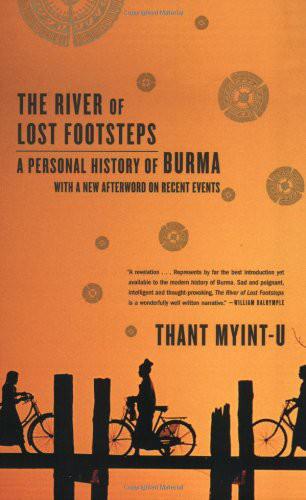

Maps

PREFACE

ONE: THE FALL OF THE KINGDOM

TWO: DEBATING BURMA

THREE: FOUNDATIONS

FOUR: PIRATES AND PRINCES ALONG THE BAY OF BENGAL

FIVE: THE CONSEQUENCES OF PATRIOTISM

SIX: WAR

SEVEN: MANDALAY

EIGHT: TRANSITIONS

NINE: STUDYING IN THE AGE OF EXTREMISM

TEN: MAKING THE BATTLEFIELD

ELEVEN: ALTERNATIVE UTOPIAS

TWELVE: THE TIGER’S TAIL

THIRTEEN: PALIMPSEST

AFTERWORD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INDEX

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

PREFACE

J

ust a few months after graduating from university in 1988, I found myself living uncomfortably but contentedly in a Burmese rebel base camp, a sometimes dusty and sometimes muddy sprawl of bamboo and thatch huts, the misty malarial rain forests of the Tennasserim hills in the near distance and young, determined-looking men and women in emerald-green uniforms milling all around.

The late morning hikes to lecture through the New England snow and slush, the long conversations over starchy dining hall meals, the spring garden parties, my friends off to medical school or their first jobs on Wall Street all seemed many worlds away. But at least for a little while I felt a sense of purpose, a sense that I was at the right place doing the right thing. Everything seemed exciting, the atmosphere always vibrant.

In August and September of that year, waves of antigovernment demonstrations had rocked Burma’s military dictatorship to its very foundations. When the uprising was finally and violently crushed, thousands of university students, from Rangoon and elsewhere, trekked over the mountains to the jungles near the border with Thailand, attempting not to flee but to regroup and restart their abortive revolution. They hoped for American support and American arms. There were rumors that American Special Forces were on their way. Some said an American battleship was already anchored offshore in the balmy waters of the Andaman Sea.

Though I had largely grown up outside Burma, I wanted as much as anyone to see real and immediate change in a country that had been sealed off by an army dictatorship since before I was born, and I was happy to team up with others of similar conviction. But I was always against violent change, not so much on principle but because I didn’t think it could work, and soon fell out with those keen on an armed revolt. I spent nearly a year in Bangkok, trying to help Burmese refugees, and then moved to Washington, where I worked with Human Rights Watch and lobbied for more effective U.S. action. I believed that maximum pressure would yield results and advocated economic sanctions.

But then I had my doubts. I came to believe that using sanctions and boycotts to isolate further an already isolated government and society was counterproductive. I was no longer sure what the most appropriate answer was. And so I stopped lobbying, removed myself from the Burma scene, and began a career with the United Nations, then in its post–cold war heyday. I served for a few years in peacekeeping operations, first in Phnom Penh and then in Sarajevo, places even worse off than Burma but where the international community would eventually take (at least in my mind) an altogether more complex and determined approach.

From Sarajevo I went back to university, this time for graduate work in modern history. I had always been interested in Burmese history, and I chose as my thesis topic the middle decades of Burma’s nineteenth century, when the ancient kingdom teetered for a while on its last legs before being vanquished by the vigorous men of Victorian England. I was fascinated by this troubled period in Burma’s past, when a Burmese government had tried to reform and failed, and by how this had helped determine the course of colonialism in the country. I began to think more about the ways in which Burma’s past influenced the present.

This book is my account of Burma’s past. It focuses on the recent past and includes stories from my own family. Though the book is roughly chronological, we start somewhere near the middle, in the autumn of 1885, when the last king at Mandalay sat nervously on the throne, when the London press relayed accounts of palace atrocities, demanding that something be done, and when British politicians plotted and planned how best to remedy, once and for all, the “Burma problem.” It’s not meant as a book for experts or primarily as a commentary on today’s problems but as a guide to the Burmese past, an introduction to a country whose current problems are increasingly known but whose colorful and vibrant history is almost entirely forgotten.

Since 1988, Burma has emerged from the shadows to assume an unenviable place in the international community, as a pariah to the West and as a concern to almost everyone else. Once known, if at all, as an exotic Buddhist land with few of the worries of the twentieth century, it’s now become a poster child for more nightmarish twenty-first-century ills, a failed or failing state, repressive and unable to cope with looming humanitarian challenges, a place whose long-enduring government seems mysteriously unwilling to cede power.

But I don’t think this is the only way to think about Burma.

Burma has always stood along the highways of Asia, connecting China, India, Tibet, and the many and varied civilizations of Southeast Asia. Her history links to the history of all these lands and beyond. Who remembers that envoys from Rome’s eastern provinces traveled through Burma to discover the markets of Han China? That in the sixteenth century Portuguese pirates, Japanese renegade samurai, and Persian princes jockeyed for power at the court of Arakan? Or the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824–26, when the rockets and steamships of the East India Company battled the elephants and musketeers of the king of Ava?

And closer to today, when thinking of Burma, who remembers the legacies of a century of British colonialism, the devastations of the Second World War, the bloody civil war of the late 1940s, or the Chinese invasions of the early 1950s?

I wrote this book also with an eye to what the past might say about the present. Since the 1988 uprising, Burma has been the object of myriad good-faith efforts, by the United Nations, dozens of governments, hundreds of NGOs, and thousands of activists, all trying to promote democratic reform. But the net result has been disappointing at best and may very well have had the unintended consequence of further entrenching the status quo and holding back positive change. And, given that result, I think it is no coincidence that analysis of Burma has been singularly ahistorical, with few besides scholars of the country bothering to consider the actual origins of today’s predicament. We fail to consider history at our peril, not only, I suspect, in the case of Burma, but in that of many other “crisis countries” around the world.

ONE

THE FALL OF THE KINGDOM