The Road to Berlin (45 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

In the ‘southern theatre’ the command changes took effect in mid-May; Marshal Zhukov formally handed 1st Ukrainian Front to Marshal Koniev, who in turn relinquished 2nd Ukrainian Front to Malinovskii. The German command considered it almost axiomatic that the Russian summer offensive would be launched by 1st Ukrainian Front jutting out into the western Ukraine. For the defence of Lvov and its surrounding area—a valuable communications centre between German troops in Poland and Rumania, and the shortest route to the upper Vistula, thence into Silesia—fresh German divisions drew up in considerable strength throughout May and early June, until some thirty-eight divisions with a powerful tank force had been concentrated. The Lvov region also lent itself to defensive operations, covered as it was by the numerous tributary rivers of the Dniester, none formidable but a hindrance to an attacker. Here the Red Army would be fighting over one of the old battlefields of the Imperial Russian Army, which in August–September 1914 had launched the offensive in Galicia that smashed the Austro–Hungarian armies and opened the way for a drive into Silesia, though not before serious misjudgment on the part of the Russian command had allowed the Austrians to escape complete encirclement and thus to fight on west of Lvov. It was an instructive lesson, which Marshal Koniev evidently put to good use. After Stalin’s April directive, 1st Ukrainian Front turned to the defensive along its 220-mile sector (running west of Lutsk, east of Brody, west of Kolomiya and Krasnoilsk) after fighting off German–Hungarian attacks which gradually petered out. German Army Group

Nord-Ukraine

meanwhile built up its strength in infantry and tank divisions.

On taking up his command Koniev went at once to 38th Army

HQ

at the centre of the front to examine plans for an offensive operation, whose form was dictated both by the terrain and by the location of German operational reserves. The northern sector was flat but marshy, the centre around Lvov hilly with numerous rivers and streams, the southern sector decidedly hilly; German reserves were grouped round Kovel, Lvov and Stanislav. At the very beginning of June Stalin telephoned Marshal Koniev and instructed him to present his plans to the

Stavka

, where he must report forthwith. Koniev’s attack plan rested principally on the idea of a double blow, one launched from the Lutsk area and aimed at Lvov itself to destroy German forces in this area: at Lutsk, Koniev proposed to mass fourteen rifle divisions, two tank corps, a mechanized corps and a cavalry corps, all with concentrated artillery support, on a six-mile breakthrough sector; on the ‘Lvov axis’, fifteen rifle divisions, four tank corps, two mechanized corps and a cavalry corps on a seven-mile breakthrough front. The ‘Lutsk assault group’ would consist of 3rd Guards Army (Gordov), 13th Army (Pukhov), 1st Guards Tank Army (Katukov) and a ‘cavalry-mechanized group’ under Baranov; the ‘Lvov group’ comprised 60th Army (Kurochkin), 38th Army (Moskalenko), 3rd Guards Tank Army (Rybalko), 4th Tank Army (Lelyushenko) and another ‘cavalry-mechanized group’ under Lt.-Gen. Sokolov. Grechko’s 1st Guards Army and Zhuravlev’s 18th Army, supported by Poluboyarov’s 4th Guards Tank Corps,

would secure the left flank of 1st Ukrainian, with Zhadov’s 5th Guards Army going into Front reserve. Koniev aimed to encircle German forces at Lvov, split Army Group

Nord-Ukraine

(hurling one part into Polesia, the other back to the Carpathians) and bring 1st Ukrainian Front to the Vistula.

The double thrust involved Koniev in both deception measures and regrouping: 1st Guards Tank Army had to be moved up against Lutsk, 4th Tank to Tarnopol, 38th Army and 18th Army were redeployed, with deception measures designed to give the impression that the tank armies were moving on to the left flank. Not that Koniev could do much to disguise either his forces or his intentions massed against Lvov, though an attack aimed towards Rava–Russkaya did stand some chance of being concealed. The double thrust had much to recommend it, and Koniev submitted his final operational plan to Stalin exactly on these lines. Stalin reacted to Koniev’s double attack exactly as he had received Rokossovskii’s proposals for Bobruisk—grave disapproval. Stalin argued that success before had been based on a single powerful thrust by fronts and now was no time to depart from this practice. Koniev, like Rokossovskii, argued back. Stalin insisted on one powerful attack in the direction of Lvov, and Koniev responded by emphasizing that a frontal attack on Lvov would merely give the German defence most of the advantages, the likeliest outcome of which must be that the Soviet offensive would fail. ‘You are a very stubborn fellow. Very well, go ahead with your plan and put it into operation on your own responsibility.’ With that, Stalin finally yielded and Marshal Koniev was free to fight as he saw fit, though he would personally suffer the consequences if the operation failed.

The day on which Stalin telephoned Marshal Koniev to prepare 1st Ukrainian Front plans, the Front commanders involved in Operation

Bagration

received the final

Stavka

directive (dated 31 May) specifying their lines of advance, objectives and the forces to be committed. The General Staff map had been finally marked up on 30 May with all the operations forming the full complex of the 1944 ‘summer offensive’. The tally of forces assigned to

Bagration

now comprised four Fronts, the Belorussian partisan formations, the Long-Range Air Force

(ADD)

and the Dnieper Flotilla (the old Volga Flotilla). Bagramyan’s orders for 1st Baltic Front specified co-operation with Chernyakhovskii’s 3rd Belorussian: after destroying forces at Vitebsk–Lepel, 1st Baltic would force the western Dvina and move into the Lepel–Chashniki area. Two armies must penetrate enemy defences south-west of Gorodka and invest the Beshenkovicha area, while other Front forces operating with right-flank armies of 3rd Belorussian Front seized Vitebsk and then moved to Lepel, covering themselves against possible German attack from Polotsk. Chernyakhovskii’s 3rd Belorussian Front would conduct its operations linked with 1st Baltic to its right and 2nd Belorussian to its left. Joint Front operations must destroy German forces in the Vitebsk–Orsha area after which 3rd Belorussian forces would make for the Berezina. Chernyakhovskii already knew of the double thrust to which his front was committed, with one attack by two armies aimed at Senno (north-west of Vitebsk) and then moving north-west

to trap the Vitebsk garrison, the second attack unrolling along the Minsk highway towards Borisov. Once Orsha and Senno fell, Chernyakhovskii was to get his armies on to the western bank of the Berezina. One reinforced army from 2nd Belorussian Front would take Moghilev, with Front forces pursuing the enemy along the Moghilev–Minsk highway as far as the Berezina. Rokossovskii’s 1st Belorussian Front received formal orders to strike two blows with two armies committed to each attack, the first from Rogachev to Bobruisk and Osipovichi, the second from Ozaricha to Slutsk: the Front assignment included the encirclement and destruction of German forces at Bobruisk, the seizure of the Bobruisk–Glusha–Glussk area, and an advance on Osipovichi–Pukhovichi and Slutsk. Rokossovskii thus was committed to two main axes, Bobruisk–Minsk and Bobruisk–Baranovichi, but until his right flank armies reached a line running west of Slonim (north-east of Brest), his centre and left-flank armies would remain stationary.

At 1600 hours on 4 June Marshal Vasilevskii, Chief of the General Staff and

Stavka

‘co-ordinator’ for 1st Baltic and 3rd Belorussian Fronts, arrived at Chernyakhovskii’s

HQ

. During the small hours of 5 June Marshal Zhukov, Deputy to the Supreme Commander and ‘co-ordinator’ for 1st and 2nd Belorussian Fronts, flew out to Rokossovskii’s

HQ

, arriving at 0500 hours and starting the operational planning three hours later. At the end of their first day’s work, both Vasilevskii and Zhukov reported to Stalin in midnight calls. Vasilevskii intimated that the situation remained unchanged, but Zhukov complained in strong terms that rail movements were falling sharply behind schedule—would Stalin therefore urge Kaganovich (head of the railways) and Khrulev (head of rear services) to speed up the movements? For a week both marshals complained in increasingly exasperated terms to Stalin about delay with rail movements: tanks, artillery, ammunition and fuel all failed to arrive either on time or in the right quantities. Vasilevskii personally asked Kaganovich to get Rotmistrov’s tank army into the area no later than 18 June. And now 2nd Belorussian Front was gasping for lorries and aircraft fuel.

During that first week in June when Zhukov and Vasilevskii worked to heave Soviet armies into the line for the enormous attack aimed at Army Group Centre, Govorov made final preparations for his attack on Vyborg (Viipuri) to wipe Finland out of the war. ‘The vast naval and ground forces’ committed to

Overlord

in the west had launched the cross–Channel invasion of 6 June. The night before the invasion the Prime Minister sent off a signal to Stalin (dated 5 June) explaining the reason for the last minute postponement, the weather conditions; now, finally, ‘proper weather conditions’ prevailed and ‘tonight we go’—all 5,000 ships and 11,000 ‘fully mounted aircraft’. The Prime Minister’s next signal followed on D-Day itself, 6 June: ‘Everything has started well. The mines, obstacles and land batteries have been largely overcome. The air landings were very successful … Infantry landings are proceeding rapidly … The weather outlook is moderate to good.’ Stalin’s reply to the Prime Minister (with a copy to the President) opened austerely and went on to specify Soviet intentions:

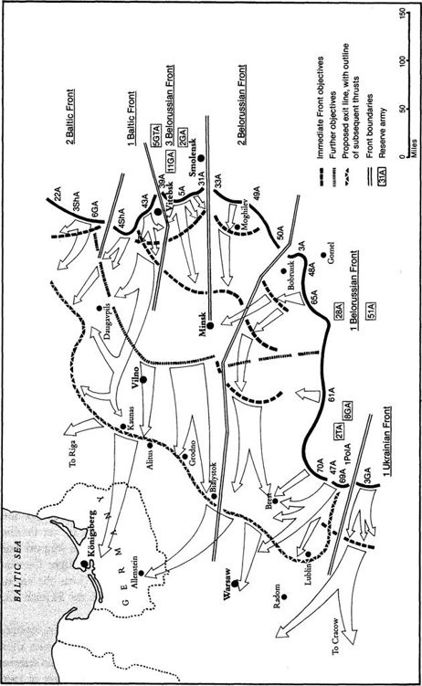

Map 7

The Belorussian offensive: 1944 General Staff planning map

The summer offensive of the Soviet troops, to be launched in keeping with the agreement reached at the Teheran Conference, will begin in mid-June in one of the vital sectors of the front. The general offensive will develop by stages, through consecutive engagement of the armies in offensive operations. Between late June and the end of July the operations will turn into a general offensive of the Soviet troops. I will keep you posted about the course of the operations.

[Perepiska

. … , vol. 1, no. 274, p. 267. ]

General Antonov, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, sent Maj.-Gen. Deane of the American Mission a copy of this text as a guide to and confirmation of Soviet intentions. Two days later (9 June) Stalin lifted one of the wrappings of secrecy shrouding the Soviet offensive by informing the Prime Minister that ‘tomorrow, June 10, we begin the first round on the Leningrad Front’.

Heavy-calibre guns had opened the ‘first round’ in the north even as Stalin drafted his message. Throughout 9 June, 240 Russian heavy guns fired at Finnish defences on the isthmus, and at dawn on 10 June after 140 minutes of intense fire supplemented by ground-attack aircraft, 21st Army took the offensive across a nine-mile front on the western side of the Karelian isthmus. The thunder of the first Russian artillery barrage carried as far north as Helsinki, more than 150 miles away; the second pre-attack bombardment was even more ferocious, hurling pill-boxes out of the ground and smashing in defensive positions. Almost 1,000 aircraft bombed and shot up the Finnish front and rear. The Soviet infantry assault was massive and fierce: on 11 June, 23rd Army attacked and on special

Stavka

orders heavy artillery followed in the wake of the infantry, with 203mm mortars being fired at a range of some 1,000 yards at the larger Finnish block-houses. From 9–13 June the big guns of the Baltic Fleet warships fired off more than 11,000 rounds. Two reserve rifle corps were thrown into the battle for the first Finnish defence line, where Govorov pressed the fierce Russian attack along the coastal road. By the evening of 15 June Soviet troops had battered their way through two Finnish defence lines, torn out a passage between Kivenappi and the gulf of Finland and prepared to drive on Viipuri. Reinforced by yet another rifle corps, 21st Army broke into the third Finnish line, the main Viipuri line. As Russian columns approached Viipuri, the Finnish command sought German help. At 1900 hours on 20 June Viipuri (Vyborg) fell. On 21 June the second Soviet offensive opened in southern Karelia, but beyond Viipuri the Finnish line, stiffened now with German men and guns, held.

At the time of the opening of the Soviet offensive against the Finns, opinion in the German command still clung to the belief that the main Soviet blow must fall in Galicia against Army Group

Nord-Ukraine

, to which German reserves were accordingly directed. Army Group Centre, thought to be the object of mere diversionary attacks, had only one division in reserve with Fourth Army and one

with Third

Panzer

, a dangerous state of affairs even for coping with a subsidiary Russian attack. At the end of May Hitler categorically forbade Army Group Centre to pull back to the Dnieper or Berezina lines. Worse was to come. Governed by the fixation about a Soviet offensive in Galicia,

OKH

withdrew LVI

Panzer

Corps in the Kovel sector from the control of Army Group Centre and subordinated in to Army Group

Nord-Ukraine

, thus gravely weakening the central sector. No longer could Army Group Centre hope to use its former tactics, so far successful, of moving up reinforcements to block or check Russian thrusts. Evidence was increasing of a massive Russian build-up against Army Group Centre, apparently deployed to smother Ninth Army at Bobruisk, concentrated against Fourth Army in the Moghilev and Orsha area, and again at Vitebsk to threaten Third

Panzer

. German intelligence was aware that divisions from the Crimea were moving up to the central sector and that 5th Guards Tank Army was also on the move to this front. There was a massive Soviet air presence. Third

Panzer

was identifying crack Soviet divisions closing on Vitebsk, a sure sign that something big was brewing. Yet even at the

OKH

conference on 14 June attended by all Army Group commanders, while Army Group Centre could point to enormous Soviet reinforcement against it, none of this evidence was taken as conclusive.

Feindbeurteilungen

and

Feindlage

, ‘enemy intention’ and ‘enemy situation’ assessments, conceded that a rapid build-up against Army Group Centre was feasible, but the idea of a Russian attack in Galicia still held sway. One intelligence report

(Agentmeldung)

dated 10 June mentioned ‘a major attack in the next ten days’ from Vitebsk and Orsha to Minsk, Baranovichi and even Vilno, but it also stated that an offensive would be directed from the Kishinev–Akermann area. As late as 20 June,

OKW

stuck to the declared view that the blow would come in the south and might be expected when the British and American armies had driven deeper from their coastal bridgeheads.