The Road to Berlin (77 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

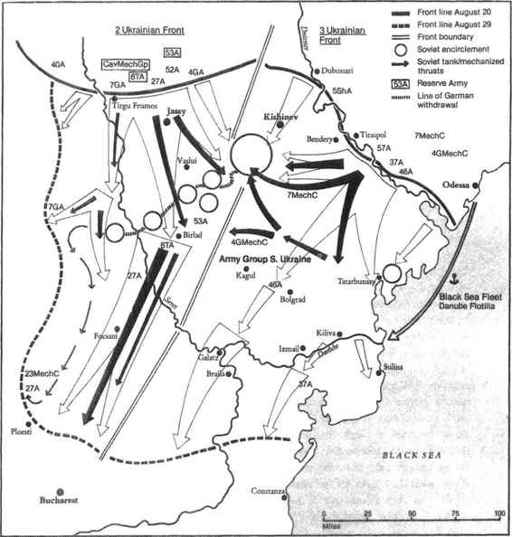

The little Rumanian country town of Husi became for a few hours the focus of the massive battle waged across Moldavia and Bessarabia. The command of Army Group South Ukraine tried to pull its troops from the south-west of Kishinev towards the river Prut, struggling at the same time to hold a few crossings over the river, a task assigned to a force passed from Eighth to Sixth Army command. Husi, a road junction and the area of the most convenient crossing points over the Prut, occupied all the attention of both the Soviet and the German command. Meanwhile on the 2nd Ukrainian Front the rapid sequence of events at the centre forced the Germans to retire from their well-prepared positions in the valley of the Siret: the fortified position of Tirgu Frumos had been in Shumilov’s hands for several hours and the town of Roman was already threatened. Units of the left flank of Eighth Army in the valley of the Siret were left with only one way out, along the road leading to Focsani, but this too was to be cut by more Russian columns. From left, right and centre, Army Group South Ukraine shuddered under these multiple blows. By the evening of the twenty-fourth the situation was entirely and uncontrollably catastrophic.

From dawn onwards on 23 August, 18th Tank Corps (2nd Ukrainian Front) was engaged in heavy fighting with elements of Sixth Army falling back on Husi and units of 52nd Army followed in the wake of 18th Corps tanks. German troops from Jassy and Kishinev were also converging on Husi and the wooded country to the south-west, the remnants of three German and four Rumanian divisions, whose fighting troops tried to organize some kind of defence on the eastern bank of the Prut. As Soviet tank units began to fight their way into Husi well ahead of the infantry, on the eastern bank of the Prut the forward armoured units of 3rd Ukrainian Front on August 23 were also closing on the river line at Leusini and a little to the south of it—Colonel Marshev’s 16th Mechanized Brigade and Colonel Shutov’s 64th Brigade, both belonging to 7th Mechanized Corps; Colonel Zhukov’s 36th Guards Tank Brigade from 4th Mechanized Corps captured the Prut crossing north of Leovo at about the same time. Once on the river the tank crews, baked in their hot machines, stopped long enough to strip off their overalls and bathe, looking like a group of village lads as they splashed about. The brief rest was well earned: the Soviet pincers forming the inner encirclement had all but met, trapping five German corps, the bulk of them pinned on the eastern bank of the Prut. In the woods south of Kishinev the remnants of ten German divisions sought what cover and protection they could find; on Tolbukhin’s left flank the Rumanian 3rd Army was by now completely encircled. Soviet troops finally cleared Bendery on 23 August and hoisted the red flag of victory.

Map 10

Jassy-Kishinev operations, July–August 1944

23 August 1944 proved to be one of the decisive days of the entire war. With Russian tanks on the Prut and more racing south for the ‘Focsani gap’, the fate of an entire German Army Group hung in the balance, proof of the massive and effective Russian battlefield performance in Moldavia and Bessarabia. That alone, however, could not make one single day so momentous. What changed the fortune of Germany’s entire south-eastern theatre was the

coup

carried out that day in Bucharest, when King Michael had the Antonescu brothers arrested and Rumania ceased to fight alongside Germany. Rumanian troops were instructed to cease firing on the Red Army and King Michael surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. Hitler had already confessed at the end of July that ‘the Balkans are my major worry’, yet on 22 August General Warlimont could scarcely believe his ears when the Balkan crisis was discussed without any reference to the dangerous situation in Rumania. Hitler treated the German commander-in-chief in the south-eastern theatre to a ranting attack on ‘the danger of a greater Serbia’, concentrating on Tito at a time when the Russians were over the Dniester and the Prut and about to drive through ‘the coastal front’ in the south-east. German opinion about Rumania persisted in the belief that the Soviet invasion would force the Rumanians to fight on to the end. Nor was anything said of Bulgaria, Germany’s other ailing ally, save for an almost inconsequential remark that the Bulgarians might pull their troops out of Serbia and must be replaced by German troops.

The Rumanian defection of 23 August turned Germany’s military defeat into a welling catastrophe which made itself felt far beyond the bounds of a single Army Group. What was left of the two Rumanian armies fighting with Army Group South Ukraine laid down their arms: one German army, the Sixth, was being slowly throttled at Kishinev and was inside the encirclement ring: the whole of southern Bessarabia, the Danube delta and the passes through the Carpathians lay wide open to the Red Army. Neither the Danube nor the Carpathians could bar the Russian advance. Ahead of the Soviet armies lay the route to the Hungarian plains, the gateway to Czechoslovakia and Austria, as well as the road to Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, the collapse of the entire German defensive system in the south-eastern theatre. All this was precipitated by the Bucharest

coup

.

The date originally fixed by the Rumanian conspirators for their

coup

was 26 August, but the rapid deterioration of the situation in view of the disasters at the front made keeping to a ‘timetable’ pointless. Iuliu Maniu nevertheless seemed inclined to wait still longer but the senior officers associated with the opposition pressed for action even without informing the Rumanian representatives in Cairo. The Communists and their Military–Revolutionary Committee were also sounding out the possibility of immediate action. At one of the last sessions of the Council of Ministers Marshal Antonescu found himself finally forced to confess that the army was slipping out of his control and the troops could scarcely be blamed for not fighting as energetically as they might against the Russians; threats of dire punishment no longer produced any effect upon the Rumanian soldiers who were facing far greater terrors at the front. Shortly after 9 o’clock on the morning of 23 August Colonel Dragomir, chief of staff to 4th Army, telephoned General Sanatescu at the palace with the news that the front was wholly shattered: Russian tanks were pouring through a sixty-mile gap, and the hope of any effective resistance was utterly gone. The German command forbade Rumanian officers to give orders but nothing was being done to save the army. Dragomir appealed for help and for ‘influence’ to be brought upon the Germans.

General Sanatescu expressed great astonishment at this news, which acted as one more stimulus to change Rumania’s course. A communist emissary to Iuliu Maniu was evidently brushed off somewhat abruptly with the observation that armistice talks should be initiated by the Antonescus: Constantin Bratianu of the National Liberals did not even attend this hasty council of war. But on the morning of 23 August Maniu, Petrescu and Bratianu did meet to plan their approach to Marshal Antonescu; Bratianu was selected as the spokesman for the ‘historical’ parties, who now pressed the Marshal to seek an armistice or else retire from the political scene. The position of the king now assumed extraordinary importance. He had already advised Cairo through his private channels of the intention to act in a few days’ time, but the arrival at the palace of the Antonescu brothers on the afternoon of the 23rd produced an unforeseen climax: Ion Antonescu informed the king that he intended to seek an armistice though he would tell the Germans of his plans to do so. Aware that this could only prolong the agony and must inevitably bring down the wrath of both Russians and Germans upon Rumania, the king made his own decision on the spot. Going into an adjoining room he instructed his friends to arrest the Antonescu brothers.

In place of the Antonescus, King Michael established his own government with General Sanatescu at its head, a non-political figure who represented the armed forces: Niculescu-Buzesti took over foreign affairs, General Aldea internal affairs, and four representatives of the main parties joined the government—Maniu, Bratianu, Petrescu and Patrascanu (the latter for the Communists and, as a lawyer, installed as minister of justice). In the evening the king spoke to the nation and to the outside world over the radio, announcing an end to all fighting and hostile acts. Through a British officer in Bucharest he addressed an

urgent appeal for three parachute brigades to be dropped near the Rumanian capital. On behalf of the new government, Niculescu-Buzesti sent a signal to the Rumanian representatives in Cairo authorizing them to sign an armistice on the terms originally proposed by the Allies on 12 April, though the new foreign minister drew attention to the concessions mentioned by Mme Kollontai—the Rumanian economy could not bear excessive reparations and the Rumanian government must be left an integral piece of Rumanian territory from which Soviet troops would be barred.

The day’s developments in Bucharest took the Germans completely unawares. Hitler that evening ordered all military units,

SS

units and German citizens to work for the re-establishment of order and to throw back the Russian offensive. The military command still hoped to pull the German armies back to a defensive line which might also cover the oil-producing regions and to ‘clean out’ the

‘putschists’

in Bucharest, thus restoring the political conditions that would keep German troops in Rumania. The German commander in Bucharest reported that the

coup

, which had come out of the blue, was only the work of a ‘palace clique’; with 5th

Flak

Division about to take over the city he reported at 0415 hours on 24 August that all the immediate steps to carry out Hitler’s orders had been taken. But the news in mid-morning was undoubtedly bad. Bucharest was in the grip of ‘heavy fighting’—

schwere Kämpfe

—in which a strong force supporting the ‘palace clique’ was besieging several German installations; the German Embassy was threatened by mobs and the German Ambassador had committed suicide. German reinforcements from Ploesti were moving on the capital and at 11 am a force of 150 German aircraft mounted an immediate bombing attack, singling out the palace as one of their prime targets. Hitler was bent on taking full and furious revenge.

While the

Stukas

were attacking Bucharest, the two Soviet fronts driving through Moldavia and Bessarabia completed the first stage of their offensive: in the area of Leovo the armoured units of 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts finally linked up, sealing the inner encirclement line. Berzarin’s 5th Shock Army was already in possession of Kishinev on the morning of 24 August. Malinovskii’s mobile columns pushed on to Bacau, Barlad and Tecuci—less than forty miles to the ‘Focsani gap’, while German troops had still twice this distance to cover in order to escape. Almost fifty miles separated the inner from the outer Soviet encirclement lines, and eighteen German divisions were trapped inside the inner ring.

In the course of 24 August the

Stavka

issued revised orders through Marshal Timoshenko to Malinovskii and Tolbukhin: the offensive was to continue on the outer encirclement line, with ‘explanations’ to the Rumanian troops—now abiding by the cease-fire order—that ‘the Red Army cannot cease military operations until such time as those German forces which continue to remain in Rumania have been eliminated’. The

Stavka

also intimated that Rumanian units which surrendered voluntarily and came over to the Soviet lines in a body should not

be disarmed, provided they agreed to wage ‘a common struggle’ against the Germans and the Hungarians. The unfortunate Rumanians were now caught between the Russians and the Germans, who also forced them to choose, though none could be found to turn traitor to the king and support the Germans: the OKW War Diary recorded that all the Rumanian generals remained

‘königstreu’

. The hasty attempt to bring back Horia Sima and install an ‘Iron Guard’ regime flopped almost at once. The bombing of Bucharest failed to produce the panic and subservience the Germans hoped for and even anticipated; rather, the German attack on the capital (and the fighting at Ploesti) brought Rumanian soldiers into action against the

Wehrmacht

, whose attempts to ‘restore order’ failed and simply helped to precipitate Rumania’s formal declaration of war on Germany on 26 August.

On the day that Rumania officially entered the war, Tolbukhin’s columns were completing the conquest of all southern Bessarabia, where Bolgrad, Kilia and Remi fell to Shlemin’s tanks, while Malinovskii’s armoured forces raced for the ‘Focsani gap’. Of the four German divisions concentrated to hold this escape route open, two were speedily withdrawn to protect German interests deeper inside Rumania, leaving only two infantry divisions to hold off Malinovskii’s rush, a hopeless task in the face of Soviet tank strength sweeping on to the ‘gap’. Inside the Soviet ring German troops, formed into three columns and covered by powerful rearguards to the north, east and south, prepared to break out, aiming to punch their way through to Husi. Malinovskii’s orders, in addition to prescribing co-operation with Tolbukhin in dealing with this sizeable German force in his rear, specified further movement to the west and south-west towards the eatern Carpathians, together with a high-speed drive through the ‘Focsani gap’ and into the central regions of Rumania.