The Road to Berlin (98 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

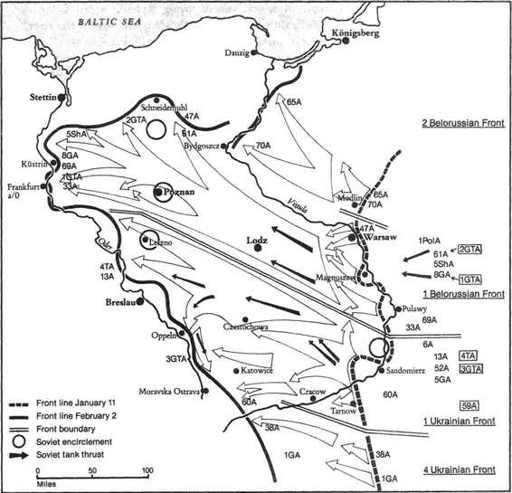

German attempts to hold the Soviet advance on the river lines of the Bzura and Rawka came to nothing as Bogdanov’s tank army—now bearing the battle honour ‘Warsaw’—crashed ahead along a north-westerly axis, though stiffer resistance meant moving up Krivoshein’s 1st Mechanized Corps as reinforcement. Taking Kutno and Gostynin, Bogdanov’s tanks drove ahead west and north-west, bumping into ‘the Netze line’ where the Germans hoped to make something of a stand. 34th Guards Rifle Brigade operating with the lead units of 12th Guards Tank Corps took Inowroclaw on 21 January, and the frozen Netze with its lakes similarly turned into ice passages was crossed the next day by 9th Guards Tank Corps. While the main body of the tank army pressed on towards Samochin and Schneidemühl, 9th Tank Corps launched a sudden attack on Bydgoszcz (Bromberg) and had cleared it by the evening of 23 January, opening the road to the

Reich

frontier, now just over forty miles away.

Map 14

From the Vistula to the Oder, January–February 1945

The honour of being the first to cross that frontier, however, fell to Marshal Koniev and the formations of the 1st Ukrainian Front. After 17 January, in response to the

Stavka’s

instructions, Koniev turned his main armoured attack north-westwards in the direction of Breslau, but the looming battle for the major industrial region of Silesia caused the Front command to make some radical re-dispositions,

the most dramatic of which was to swing Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army from north to south, thus taking it finally along the line of the river Oder. In order to dislodge the German forces without literally blasting them out of the factory towns, Marshal Koniev decided on a very skilful series of manoeuvres designed to move his armies round—rather than through—this industrial complex: while armour carried out its wide envelopment, the infantry would attack from the north, east and south in order to squeeze the German garrisons into open country where they might be more easily destroyed. North of the Vistula, Gusev’s 21st Army (reinforced with a tank and cavalry corps) would carry out the envelopment from the north and north-west, Korovnikov’s 59th Army (with Poluboyarov’s tank corps) would attack towards Katowice, and Kurochkin’s 60th Army effect the southern envelopment. In the north the lead battalions of Koroteyev’s 52nd Army had already crossed the

Reich

frontier at Namslau on 20 January together with Rybalko’s tanks from 3rd Guards Tank Army, although the main body of that formation was about to make its ninety-degree turn to bring it sweeping southwards along the line of the Oder and in the direction of Katowice. Behind them was Pukhov’s 13th Army making up the distance between Piotrkow and Wielun, driving on until they, too, crossed the German frontier near Militsch on 23 January. Meanwhile Lelyushenko’s 4th Tank Army moved westwards ahead of Pukhov, entering the Polish town of Rawicz on 22 January and pushing brigades on to the Oder—17th Guards Mechanized Brigade reached Göben on the Oder during the night of 22–23 January and a forward reconnaissance group of 16th Guards Mechanized Brigade broke through to the Oder north of Steinau (some forty miles north-west of Breslau). Zhadov’s 5th Guards Army had also advanced to the Oder north-west of Oppeln (Opole) on 22 January and captured a bridgehead on the western bank—the first seized by the 1st Ukrainian Front, though the reduction of the Silesian industrial region had to be resolved before any large-scale crossing of the Oder could be attempted.

By 25–26 January, as both Zhukov and Koniev pushed on to the Oder, the problem of co-ordinating this advance—within each separate front and between the fronts themselves—assumed new urgency. Stalin on 25 January telephoned Zhukov to interrogate him on his immediate plans: Zhukov intimated that he proposed to advance with all speed towards Kiistrin on the Oder, while his right-flank forces would swing north and north-west to fend off any possible threat from East Pomerania, though as yet no immediate danger presented itself. Stalin seemed to be far from convinced, pointing out that Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front would be separated by ‘more than 150 kilometres’ from Rokossovskii’s 2nd Belorussian Front: Zhukov must wait until Rokossovskii completed the ‘East Prussia operation’ and had his forces ‘out beyond the Vistula’, a task requiring all of ten days—nor could Koniev cover Zhukov’s left flank since his main forces were still engaged in reducing the Silesian industrial region. Zhukov pleaded at once with Stalin to be allowed to continue his offensive without any break or pause, if only to penetrate the ‘Miedzyrzecz fortified line’ at speed; an additional

army as reinforcement would secure the right flank. To this Stalin made no specific reply, save for an undertaking to ‘think it over’. Zhukov heard no more.

Undeterred for the moment, Zhukov pressed his attack, pushing Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army into the Miedzyrzecz fortified line, which proved to be disorganized and still largely unmanned. To protect these forces now advancing on the Oder from any assault from the direction of East Pomerania and to cover his right flank, Zhukov redeployed 3rd Shock Army, 47th and 61st Armies, 2nd Cavalry Corps and the Polish 1st Army to face northwards. Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army, 69th Army and part of 1st Guards Tank Army were assigned to the ‘reduction’ of Poznan, which, as Chuikov sardonically noted, was not a lightly defended city to be seized off the march, but a formidable fortress.

At this point in time all those imperfections and imprecisions of the

Stavka

directives issued at the end of November 1944 now came home to roost. On the day that Stalin telephoned Zhukov about his next moves, Marshal Rokossovskii had all but won the battle for East Prussia. Yet a gnawing crisis was building up on Rokossovskii’s left flank as he tried desperately to keep pace with Zhukov’s advance to the Oder. Zhukov’s forces remained ‘poorly protected on the north, from the direction of East Pomerania’ (which is how Rokossovskii himself described the situation) while he, in turn, was thoroughly bemused by the situation on his northern flank where Chernyakhovskii was operating. Stalin was right in pinpointing possible danger for Zhukov, but he remained ominously silent on the possible remedy and, naturally enough, did not refer to the root cause of the impending crisis.

On 14 January, as Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front went into action, Rokossovskii’s 2nd Belorussian Front opened its own offensive along the line of the river Narew, mounting the main attack northwestwards from the left flank with four infantry armies (70th, 65th, 2nd Shock and 48th Armies) and one tank army (Volskii’s 5th Guards Tank), plus one army (Gorbatov’s 3rd) in immediate reserve; on the right flank Rokossovskii deployed two armies, Grishin’s 49th and Boldin’s 50th, for an attack on Lomza and an advance through the Masurian lakes to link with Chernyakhovskii’s 3rd Belorussian Front. Rokossovskii needed speedy success above all else, yet the river Narew itself—at least 300 yards across and four yards deep—posed a formidable barrier; the late-winter frosts had laid only the thinnest screen of ice, passable for small groups rather than large bodies of men, but at least the marshes on the Russian side were frozen hard and could support a goodly force. North and south of Pulutsk Soviet troops had earlier captured two small bridgeheads, holding them for several weeks though under constant German artillery fire; from the Soviet side of the river heavy guns had duelled daily with German batteries, steadily building up their firepower. On the morning of 14 January, when mist and swirling snow storms cut visibility to a hundred yards, Rokossovskii’s Front fired off an artillery barrage at 10 o’clock, heavy gunfire which lasted for most of the day and was concentrated for the most part against Pulutsk. But the same foul weather kept Soviet aircraft

grounded. Deprived of air support and with tank operations limited by dense mist, the brunt of the fighting fell on the infantry. Rokossovskii disposed of much armour and many guns but was seriously short of infantry, in spite of his divisions having been filled out on the eve of the attack with 120,000 men—10,000 were liberated

POWS

, 39,000 returned from field hospitals and 20,000 flushed out of rear services and supply units, with many more local conscripts pressed into the Red Army.

Progress was disappointingly slow on this first day and, on the next day, Gorbatov’s 3rd Army had to hold off powerful attacks launched by

Grossdeutschland Panzer

units (shortly to be transferred south to Kielce, to fight against Koniev) with all the danger that German troops might break into the flank and rear of the main Soviet assault force. Gorbatov held on, the attacks slackened and Rokossovskii, for all his reluctance, decided to commit two tank corps alongside 48th, 2nd Shock and 65th Armies to smash in the German defences.

With the Pulutsk fortified area outflanked, the defenders fell back, though the German command rushed up reinforcements to cover the approaches to Mlawa. The weather improved on 16 January, Soviet ground-attack aircraft joined the battle and N.I. Gusev’s 48th Army, supported by 8th Mechanized Corps, battered its way forward. Ciechanow, more than thirty miles to the west of the Narew, fell to Soviet troops, and the capture of this important road junction began to signal a major breakthrough. The next day, 17 January, Volskii’s 5th Guards Tank Army was committed into the breach effected by 48th Army; Soviet columns were now advancing on Mlawa and had crossed the river Wkra on a wide front. Prasznysz at the centre of the front was captured on 18 January, Popov’s 70th Army took the old fortress town of Modlin, and German attempts to escape along the motor-road to Plonsk were dashed as Batov’s 65th Army took Naselsk and Plonsk. Within twenty-four hours the 2nd Belorussian Front had broken through the German defences along a sixty-mile front running from Modlin to Ostrolenka, to a depth of some 35–40 miles. Mlawa itself fell on 19 January and the way was cleared for Rokossovskii to lunge far beyond the Vistula.

The next day, 20 January, produced a major shock for Rokossovskii. The

Stavka

ordered him to turn three infantry armies—3rd, 48th and 2nd Shock—plus 5th Guards Tank Army to the north and north-east against German forces in East Prussia, aiming at the Frisches Haff. These revised operational orders clearly cut across the formal provisions (and informal understandings) of the main

Stavka

directive of 28 November 1944, which had envisaged close and effective co-ordination between the 1st and 2nd Belorussian Fronts in the entire ‘Vistula–Oder operation’. Rokossovskii was left with his initial assignment—co-operation with 1st Belorussian Front—but now burdened with the task of surrounding German forces in East Prussia. In view of the

Stavka’s

latest orders, Rokossovskii could commit only two armies on his left flank in support of Zhukov’s drive on the Oder, a state of affairs which brought a burst of fierce anger from Zhukov himself.

Chernyakhovskii’s offensive with 3rd Belorussian Front had already begun on 13 January, when assault battalions moved forward on the eastern frontier of East Prussia at 6 o’clock in the morning, screened by dense mist—though the same mist drastically reduced the effectiveness of the massive artillery barrage, involving an expenditure of almost 120,000 shells, fired off against the fortified lines between Pilkallen and the river Goldap. The Front attack plan called for an assault from the centre of the Front and a westerly drive to destroy the ‘Tilsit–Insterburg’ group of German forces; Königsberg, capital and ‘citadel of East Prussia’, was the final objective. The assault armies were drawn from Lyudnikov’s 39th, Krylov’s 5th and Luchinskii’s 28th, with Galitskii’s 11th Guards Army as a second-echelon formation assigned to eliminate German defences north of the Masurian lakes. P.G. Chanchibadze’s 2nd Guards Army was allotted the task of securing the left flank of this assault force, which might be attacked from the direction of the Masurian lakes; Shafranov’s 31st Army was deployed on the extreme left flank to hold German units in a covering action. The Front command determined that it was opposed by thirteen German infantry divisions and one motorized division, part of Third

Panzer

and Fourth Armies.

Chernyakhovskii’s formations had literally to batter in German defences, slogging bloody battles in the midst of prepared German defences, from which Soviet assault troops were met by fierce counter-attacks. Both sides suffered heavy losses. The main Soviet thrust was concentrated north of Pilkallen, though the German command waited for an attack to develop south of Gumbinnen. On 16 January Chernyakhovskii loosed his main attack in full force, when Soviet tanks crossed the frozen marsh between Schillehnen and the river Sheshupe. Schillehnen was outflanked and Lasdehnen taken. A sudden improvement in the weather brought the Soviet air force on to the battlefield and in support of Burdeinyi’s 2nd Guards Tank Corps. Kyudinikov’s 39th Army, with close air support provided by Khryukin’s 1st Air Army, took Schillehnen and pressed on over the Sheshupe; Lt.-Gen. V.V. Butkov’s 1st Tank Corps was committed alongside 39th Army and moved to outflank Tilsit from the south. On 19 January the

Stavka

handed over Lt.-Gen. A.P. Beloborodov’s 43rd Army (1st Baltic Front) to Chernyakhovskii, for use in operations against Tilsit and the subsequent drive on Königsberg. Pilkallen, attacked now from three sides, fell on 18 January, having resisted so many Soviet frontal attacks, and the next day Tilsit was in Soviet hands, after which Soviet tank columns struck along the Königsberg road and were well on their way to Insterburg.