Authors: Nicholas Clapp

The Road to Ubar (13 page)

More maskoot are found in the tale "The City of Brass," by all odds the most bizarre rendition of the Ubar myth. It is phantasmagoric, funereal. It recounts the adventures of Emir Musa and his companions as they set out from the sea in search of a mysterious lost city. They are directed across a great desert by a brass horseman, then by a djinn (or genie) mired up to his armpits in a furnace. The way "is full of dozens of frights, full of wonders and strange things." Emir Musa's little group finally climbs a hill, and...

When they reached the top, they beheld beneath them a city, never saw eyes a greater or goodlier, with dwelling-places and mansions of towering height, and palaces and pavilions and domes gleaming gloriously bright ... and its streams were a-flowing and flowers a-blowing and fruits a-glowing. It was a city with gates impregnable; but void and still, without a voice or a cheering inhabitant. The owl hooted in its quarters; the bird skimmed circling over its squares and the raven croaked in its great thoroughfares weeping and bewailing the dwellers who erst made it their dwelling.

5

Within its walls, the city is a showcase of death, at once splendid and the stuff of nightmares. Its streets and palaces are filled with ghastly long-dead maskoot. The queen of Sheba even makes a cameo appearance. Reclining on a bejeweled couch, she appears as "the lucedent sun, eyes never saw a fairer." But..."she is a corpse embalmed with exceeding art; her eyes were taken out after her death and quicksilver set under them, after which they were restored to their sockets. Wherefore they glisten and when the air moveth the lashes, she seemed to wink and it appeareth to the beholder as though she looked at him."

Everywhere in this city of the petrified are graven inscriptions that drive home the moral message:

the pleasures of immense richesâhere everywhere in evidenceâare for naught, for life is brief and death almighty.

This powerful idea is central to medieval Islam. As a legend over the tomb of the son of King Shaddad ibn 'Ad tells us: "Be warned by my example. I amassed treasures beyond the competence of all the kings of the earth, deeming that delight would still endure to me. But there fell on me unawares the Destroyer of delights and the Sunderer of societies, the Desolator of domiciles and the Spoiler of inhabited spots." The angel of Death.

Though its message and central story line are relatively simple, "The City of Brass" in its entirety is a dense, complex tale, a concatenation of imagery and characters from diverse times and places. Emir Musa appears to be an incarnation of the Old Testament's Elijah. And what are not only the queen of Sheba but Solomon and Alexander the Great doing here? The tale, packed with hundreds of allusions, is based on at least eight major sources. Indeed, the brass city itself appears to be inspired not only by Ubar but by rumors of a town of copper and brass located either in North Africa or in Spain. To accommodate these rumors, whoever wrote the tale whisked Ubar and its People of 'Ad from Arabia and plunked them down in Andalusia!

"The City of Brass" is ultimately surreal, beckoning us ever onward into a sun-drenched yet sinister landscape that "is like unto the dreams of the dreamer and the sleep-visions of the sleeper or as the mirage of the desert, which the thirsty take for water; and Satan maketh it fair for men even unto death."

The tale draws to a close with hardly a glimmer of Ubar as a real place. If mythmaking can be likened to a mirageâhiding yet reflecting a distant realityâthat mirage has finally become all but impenetrable. Emir Musa and his companions take leave of the sepulchral brass city they have discovered and retrace their steps across the desert to the sea. But then, in the span of a single sentence, the mirage fleetingly dissolves. We are told that the emir's party "came in sight of a high mountain overlooking the sea and full of caves, wherein dwelt a tribe of blacks, clad in hides, with burnooses also of hide and speaking an unknown tongue."

Here, quite unexpectedly, is a sudden cluster of clues.

1. "a high mountain overlooking the sea and full of caves ..." In all of Arabia, the

only

seaside peaks known for their caves are the Dhofar Mountains in southern Oman.2. "caves, wherein dwelt a tribe..." The peninsula's only cave dwellersâpast or presentâare tribes of the Dhofar Mountains.

3. "a tribe of blacks..." The people of the Dhofar Mountains are distinctly dark-skinned.

4. "clad in hides, with burnooses also of hide..." Hides come from cattle, and there is only one area of Arabia where within the past 4,000 years cattle have been a mainstay of a tribe's livelihood: the Dhofar Mountains.

5. "and speaking an unknown tongue." The Dhofar Mountains are the

only

area where a language other than Arabic is spokenâan ancient language, only recently studied.

6

Were these legitimate clues? Or was this a cluster of incredible coincidences? In any case, if we ever found the wherewithal to search for Ubar, we would begin our journey

at the foot of the Dhofar Mountains.

We would cross these mountains, where to this day dark-skinned people raise cattle and speak a strange language. Until recently, they dwelt in caves.

This was the logical route to our search area in the desert beyond. In following it, we would be setting out in the footsteps of Bertram Thomas, Wendell Phillipsâand now, apparently, Emir Musa of the

Arabian Nights.

A

T THE TURN OF

1990 I was at work, alone, sorting out paperwork for a documentary film for Occidental Petroleum. I gazed out the window of my office at the company's Los Angeles headquarters, and instead of steel and glass towers saw the sands of Arabia. Was Ubar really out there? Or was it only a city of the imaginationâas real as brass horsemen, djinns in furnaces, and queens with quicksilver eyes.

The phone rang. It was George Hedges. "We got a letter from Yahya," he said. His voice was curiously flat, as if he was feigning nonchalance.

Yahya. Another mystic? Like the Count, like Jorsh?

"Yahya..." George repeated. "According to his letterhead, he's with the Oman International Bank. They want to sponsor us."

George explained that Barry Zorthian, the ex-CIA operative we had met in Washington, had brought our project to the attention of Dr. Omar Zawawi, chairman of the Oman International Bank. A physician and philanthropist as well as entrepreneur, Dr. Zawawi liked the idea of looking for Ubar and asked his associate Yahya Abdullah to contact us. If we could make a brief preliminary trip to Oman, Dr. Zawawi's bank would not only pay our way but help us enlist additional sponsors, who would either help underwrite the expedition or donate services and equipment. At the same time we could get a feel for the problems we would face and perhaps even fit in a quick reconnaissance of our search area.

"How about that?" said George with a deep and heartfelt sigh. "At last!"

We called Juri Zarins. He was delighted with the news. At the time he was researching the demand for incense in the ancient kingdoms of Mesopotamia, a need that may have been met by shipments from Ubar.

We called Ran Fiennes. With the influential Dr. Zawawi behind us, Ran felt that permission would be granted for at least an Ubar reconnaissance. There was a hitch, though. Ran was about to set out on another Arctic adventureâa walk, unassisted by machine or dog, to the North Pole. The earliest he could fit in the Ubar reconnaissance was the following summer. We settled on the last two weeks in July. Considering that nearly ten years had gone by, what was another few months? The delay, in fact, would give us time to analyze some space imaging that was due in, in fact overdue, from the French SPOT satellite.

At the Jet Propulsion Lab, Ron Blom and Charles Elachi were delighted that an expedition was now possible. "But," Ron grumbled, "I don't get it."

"Get what?" I asked.

"What's wrong with the French?" What Ron had in mind was their inexplicable delay in forwarding computer tapes of the SPOT satellite's pass over our search area. It was not as if JPL/NASA had written a bad check.

Ron called the SPOT people and got the verbal equivalent of an exasperated shrug. The reason for the delay, they explained, was that the satellite had twice overflown our search area, and twice sent back unusable images. Too many clouds.

Clouds in the Rub' al-Khali? Unlikely, Ron thought. And then he recalled that the French routinely spot-checked incoming images with low-resolution, low-quality scans. "Perhaps you're not seeing clouds at all," he suggested. "Perhaps those clouds are dunes."

They were. And a month later we had images that were worth the wait. In black-and-white rather than color, they had triple the resolution of our previous Landsat 5 shots. The road to Ubar was razor sharp and clearly visible as it ran far out into the dunes of the Rub' al-Khali.

As I studied the image, absorbed in what might lie along the Ubar road, Ron and Bob Crippen whispered back and forth; I caught phrases like "computer waypoints" and "pixel registration."

"We can do better," they announced.

What they had in mind was a computer-generated merge of data from our Landsat 5 and SPOT images. The result would be a single image that had the sharpness of the black-and-white SPOT data

and

the rich color of the Landsat 5 imagery. It was a technologically daunting idea. Two disparate pictures, taken years apart from different altitudes and angles, with different lenses, would have to be precisely overlaid: 36,000,000 pixels of SPOT information superimposed on 16,262,000 pixels of Landsat 5 information.

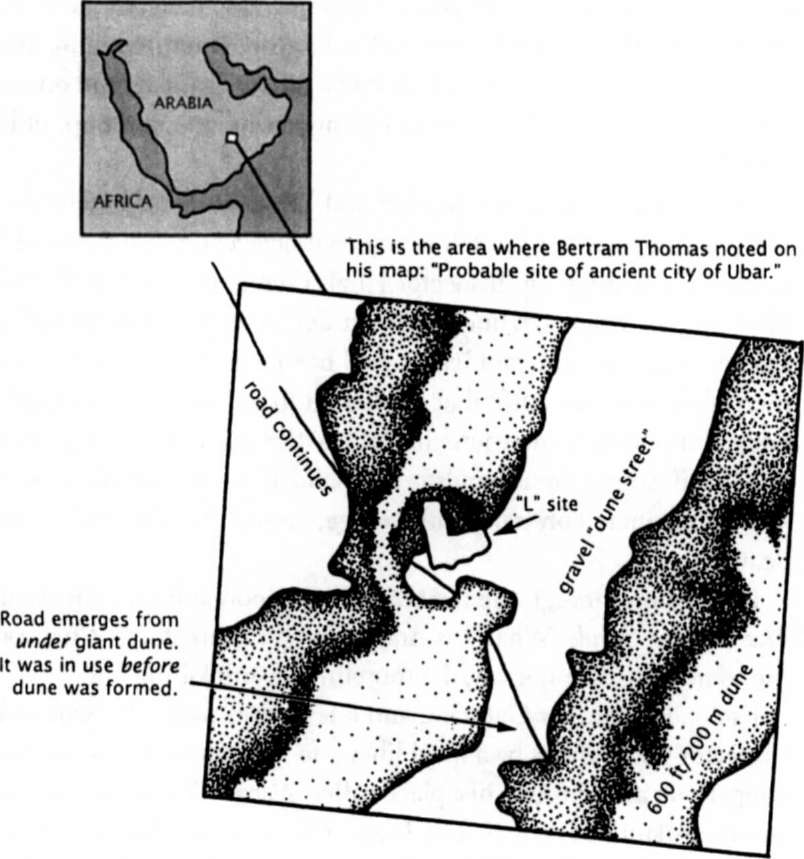

It worked, and the merged image was detailed and dazzling. If the expedition did go forward, we had plenty of candidates for Ubar to check out. The most promising was one we named the "L" site. Our "road to Ubar" led to a sharply defined L (400 by 400 meters) that appeared to be man-made. It could be an agricultural areaâor even a walled, ruined city. There was nothing remotely like it anywhere else on our images.

In early May I compiled a list of coordinates of points of interest along our road and faxed them to Ran, who in turn forwarded them to the Omani military authorities. There was a chance that we could have the use of a military aircraft for our reconnaissance. If so, we had a flight plan.

At about this time a very curious thing happened. Finding myself with an unexpected few days off, I decided to take a break not only from filmmaking but from the Ubar project. I was getting a little obsessive about it, to say the least. In our garage I dusted off my

Landsat 5 / SPOT composite image of the Ubar road

thirty-year-old Raleigh bicycle. Though a clunker by current standards, it had in recent years taken me on longer and longer solos out across the deserts of the Southwest. What could be better than a swing out across the Mojave, then through Joshua Tree National Monument, and on into my favorite desert, the Anza-Borrego? It would be good exercise. I'd enjoy clear air, sweeping scenery, and, for company, a couple of paperback mysteries. My daughter Jennifer recommended I take something by the English writer Josephine Tey. I picked

The Singing Sands,

which had a rod, reel, and a trout on the cover; it appeared to be a tale of fishing and felony in damp, dull-skied Scotland.

And it was ... until my Raleigh and I stopped for Gatorade and pretzels (lunch when I'm left to my own devices) in the shade of a sandstone outcropping. Inspector Hugh Grant, Tey's Scotland Yard detective, has been puzzling over a murder on the London-Aberdeen sleeper. The victim, Grant learns, had been a pilot for Orient Commercial Airlines, an outfit that ran freight to southern Arabia. Grant conjectures that somewhere in Arabia the pilot may have been driven off course by a windstormâand from the air discovered something incredibly rare and strange, something that led to his death.

I cycled on through the heat of the afternoon and thought about

The Singing Sands.

What was Arabia doing in this story? What was the something the pilot saw, the something worth killing for?

I stopped again for Gatorade and a few more pages. In Scotland, Inspector Grant drops by a local library to read up on Arabiaâand happens on a description of a place called Wabar: "Wabar, it seemed, was the Atlantis of Arabia. The fabled city of Ad ibn Kin'ad. Sometime in the time between legend and history it had been destroyed by fire for its sins.... And now Wabar, the fabled city, was a cluster of ruins guarded by the shifting sands, by cliffs of stone that forever changed place and form; and inhabited by a monkey race and by evil jinns."

1

Ubar! I sank down by the edge of the road and read on. A character based on Harry St. John Philby or Wilfred Thesiger, it is hard to tell which, is drawn into the plot. I suspected that one of the two men had rubbed Josephine Tey very much the wrong way, for the character is querulous, effete, a creature of "pathological vanity." Had Harry or Wilfred snubbed Josephine? And now, with this mystery, was she having her revenge?

As the sun fell lower in the sky, I wondered if perhaps Ubar had already been discovered and

The Singing Sands

was a fictionalization of what had happened! Although the Philby-Thesiger character doesn't find Ubar, someone else does. Sitting down to his coffee and scones, Inspector Grant opens the morning edition of the London

Clarion

and is startled by the headline "

SHANGRI-LA REALLY EXISTS. SENSATIONAL DISCOVERY. HISTORIC FIND IN ARABIA.

"