The Rogue Crew (11 page)

Authors: Brian Jacques

“Give me that beaker, please. Hold her head up gentlyâit looks like she's been knocked out cold. I don't know what injuries she may have taken. Dorka says she tumbled the length of the stairs, right into the locked door.”

The Friar watched anxiously as cordial dribbled over the old hedgehog's chin. “She just pushed past meâthere wasn't anything I could do!”

Foremole patted the watervole's paw. “Thurr naow, marm. Et wurr no fault o' your'n!”

To everybeast's amazement, Twoggs's eyelids flickered open. She licked her lips feebly, croaking, “Hmm, that tastes nice'n'sweet. Wot is it?”

Foremole wrinkled his velvety snout secretively. “It bee's dannelion'n'burdocky corjul, marm. Thurr's ee gurt barrelful of et jus' for ee, when you'm feels betterer.”

Twoggs gave a great rasping cough. She winced and groaned. “I 'opes I didn't break none o' yore fine stairs. . . .”

Abbot Thibb knelt beside her, wiping her chin with his kerchief. “Don't try to speak, marm. Just lie still now.” He cast a sideways glance at Sister Fisk, who merely shook her head sadly, meaning there was nothing to be done for the old one.

Twoggs clutched the Abbot's sleeve, drawing him close. The onlookers watched as she whispered haltingly into Thibb's ear, pausing and nodding slightly. Then Twoggs Wiltud extended one scrawny paw as if pointing outside the Abbey. Abbot Thibb still had his ear to her lips when she emitted one last sigh, the final breath leaving her wounded body.

Friar Wopple laid her head down slowly. “She's gone, poor thing!”

Thibb spread his kerchief over Twoggs Wiltud's face. “I wish she'd lived to tell me more.”

Sister Fisk looked mystified. “Why? What did she say?”

The Father Abbot of Redwall closed his eyes, remembering the message which had brought the old hedgehog to his Abbey. “This is it, word for word, it's something we can't ignore.

“Redwall has once been cautioned,

heed now what I must say,

that sail bearing eyes and a trident,

Will surely come your way.

Then if ye will not trust the word,

of a Wiltud and her kin,

believe the mouse with the shining sword,

for I was warned by him!”

heed now what I must say,

that sail bearing eyes and a trident,

Will surely come your way.

Then if ye will not trust the word,

of a Wiltud and her kin,

believe the mouse with the shining sword,

for I was warned by him!”

In the uneasy silence which followed the pronouncement, Dorka Gurdy murmured, “That was Uggo Wiltud's dream, the sail with the eyes and the trident, the sign of the Wearat. But my brother Jum said that he'd been defeated and slain by the sea otters.”

Abbot Thibb folded both paws into his wide habit sleeves. “I know, but we're waiting on Jum to return and confirm what he was told. I think it will be bad news, because I believe what old Twoggs Wiltud said. The mouse with the shining sword sent her to Redwall, and who would doubt the spirit of Martin the Warrior?”

8

Each day, as the

Greenshroud

ploughed closer to the High North Coast, Shekra the Vixen became more apprehensive. She feared the sea otters, those wild warriors of Skor Axehound's crew, who revelled in battling. Shekra had never seen the Wearat defeated until he encountered Skor and his creatures. The vixen was a Seer, but she was also a very shrewd thinker. No matter what refinements had been added to his vessel, she knew that corsairs, and searats, would be foolhardy to attack the sea otters on their own territory. Recalling the vermin bodies floating in a bloodstained sea and the blazing ship limping off, savagely beaten, Shekra was certain a second foray would only result in failure. Through listening to the gossip of those who had been aboard on that bumbled raid, it was obvious that they were of a like mind with her. However, it did not do to discuss such things with Razzid as captain. Moreover, Mowlag and Jiboree, the Wearat's closest aides, were ever on the alert for mutinous talk.

Greenshroud

ploughed closer to the High North Coast, Shekra the Vixen became more apprehensive. She feared the sea otters, those wild warriors of Skor Axehound's crew, who revelled in battling. Shekra had never seen the Wearat defeated until he encountered Skor and his creatures. The vixen was a Seer, but she was also a very shrewd thinker. No matter what refinements had been added to his vessel, she knew that corsairs, and searats, would be foolhardy to attack the sea otters on their own territory. Recalling the vermin bodies floating in a bloodstained sea and the blazing ship limping off, savagely beaten, Shekra was certain a second foray would only result in failure. Through listening to the gossip of those who had been aboard on that bumbled raid, it was obvious that they were of a like mind with her. However, it did not do to discuss such things with Razzid as captain. Moreover, Mowlag and Jiboree, the Wearat's closest aides, were ever on the alert for mutinous talk.

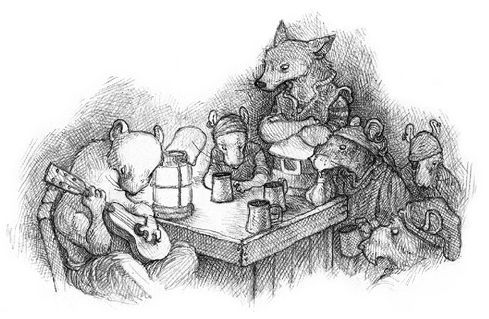

Shekra knew it was a dangerous situation to which a solution had to be found. Some serious thinking was called for. The answer came one evening, sitting in the galley with other crewbeasts. It was after supper as they were sipping grog when an old corsair stoat began plinking on an unidentifiable stringed instrument and singing. It was a common vermin sea song, full of self-pity induced by swigging quantities of potent grog. Shekra listened to the singer's hoarse rendition.

“O haul away, mates, haul away, hark 'ow the north

wind wails.

There's ice upon the ratlines, in the riggin' an' the sails!

wind wails.

There's ice upon the ratlines, in the riggin' an' the sails!

Â

“When I were just a liddle snip, me mammy said t'me,

Don't be a corsair like yore pa, 'tis no good life at sea.

O follow not the searat's ways, or ye'll be sure to end

yore days,

beneath the cold an' wintry waves, 'cos corsairs 'ave no

graves!

Don't be a corsair like yore pa, 'tis no good life at sea.

O follow not the searat's ways, or ye'll be sure to end

yore days,

beneath the cold an' wintry waves, 'cos corsairs 'ave no

graves!

Â

“O haul away, mates, haul away, hark 'ow the

north wind wails.

There's ice upon the ratlines, in the riggin' an' the sails!

north wind wails.

There's ice upon the ratlines, in the riggin' an' the sails!

Â

“I scorned wot my ole mammy said, now lookit me

t'day,

aboard some vermin vessel, o'er the waves an' bound

away.

The cook is mean, the cap'n's rough, I lives on

grog'n'skilly'n'duff

I tell ye, mates, me life is bad, now I'm grown old an'

sad.”

t'day,

aboard some vermin vessel, o'er the waves an' bound

away.

The cook is mean, the cap'n's rough, I lives on

grog'n'skilly'n'duff

I tell ye, mates, me life is bad, now I'm grown old an'

sad.”

Shekra passed the singer a beaker of grog. “Aye, 'tis right, mate, but once ye follow the sea, there ain't no goin' back. I know 'tis too late now, but tell me, wot would ye have done, if'n you'd stopped ashore? Been a farmer mayhaps?”

The old stoat chuckled humorlessly. “Wot, me be a farmer? Huh, sounds too much like 'ard work. I would've liked t'live the easy life, in some sunny ole place. Aye, with others to cook me vittles, an' a nice soft bunk t'sleep in. Where yore sheltered from storms an' cold in the winter, wid a big roarin' log fire to toast me whiskers by. Ah, that'd be wot I'd 'ave liked!”

Shekra nodded, her brain working furtively. “It sounds good t'me. Wonder if'n there is such a place.”

A youngish searat offered a suggestion. “That big stripedog mountain place, where all the rabbets lives, that looked alright t'me.”

The vixen sounded scornful, knowing which way she was leading the conversation. “No chance of gettin' anywhere near that mountain. Those rabbets are warriors, just like the wavedogs. Ye'd be slain afore ye knew it. Now, the Red Abbey place, that'd suit me. D'ye know it?”

The youngish searat shook his head. “Red Abbey place?”

The cook, a fat greasy weasel, dipped a tankard into the grog barrel. “Aye, I've 'eard tell of it. Ain't it rightly called the Red Abbot place?”

Shekra nodded slyly. “Right, mate. Wot've ye 'eard tell?” The cook finished half his tankard in one swig and belched. “Somewheres in mid-country it is, with a forest growin' round. My granpa saw it once. Said it was all built o' red stones. Woodlanders, treemice, 'edgepigs, mouses an' such lives there. They ain't short o' vittles neither.”

Shekra added her own embellishment to the cook's narration. “Aye, somebeast once told me there's orchards there with ripe fruit 'angin' off all the trees. Strawberries too, blackberries, enough honey to sink a ship, a big lake full of fishes, birds an' eggs, many as ye please!”

The old stoat singer shook his head wistfully. “The Red Abbot place, eh? Sounds wunnerful. Why ain't we been there? Woodlanders ain't warriors like wavedogs'n'rabbets.”

The vixen shrugged. “'Cos it's in mid-country an' ships couldn't reach it. Corsairs don't go nowhere widout their ships. But wot am I talkin' about? This

Greenshroud

can go anyplace nowâland or sea, it don't matter, do it?” An air of excitement suddenly pervaded the galley.

Greenshroud

can go anyplace nowâland or sea, it don't matter, do it?” An air of excitement suddenly pervaded the galley.

“We could go there, I'd wager we could!”

“Hah, wouldn't be no trouble slayin' a load o' woodlanders!”

“Aye, an' it'd all be ours, just for the takin', mates!”

“We'd live like cap'ns an' . . . an' . . . er, kings. I wonder if'n their grog's any good, Shekra.”

Now she had sown the seed, the vixen left the galley, calling back to her shipmates, “They've prob'ly got cellars loaded with barrels o' the finest drinks, or they should 'ave, wid all that fruit juice. It might taste nice an' sweet!”

She wandered out on deck. It was a fine spring night, with a hint of summer promise on the breeze. Jiboree came down from the stern deck. “Ahoy, vixen, where've ye been? Cap'n Razzid wants ye.” Wordlessly, Shekra followed him to the master cabin.

The Wearat was taking supper with Mowlag and Jiboree. Wiping moisture from his damaged eye, he glared at Shekra through his good one. It was always unnerving to be scrutinised by his cold stare.

Shekra tugged an ear in salute, unsure of why she had been summoned. “Cap'n?”

Razzid put aside the grilled herring he had been nibbling, keeping Shekra waiting as he wiped his lips and drank from a fine crystal goblet of good-quality grog. He spoke just the one word: “Well?”

Shekra swallowed hard, her paws trembling. “Did ye want me, Cap'n?”

The Wearat continued to stare, knowing the effect it had.

“Well, yore my Seer, ain't ye? Tell me wot ye see.”

The vixen breathed an inward sigh of relief. “I've been waitin' on ye to ask me, sire. A moment please.” She shook out the jumble of stones, wood, shells, feathers and other objects from her pouch. Selecting what she required, she began murmuring.

“Voices of wind and water, say

what fate may bring this Greatbeast's way,

Omens of earth, of wood and stone,

is thy message for him alone?”

what fate may bring this Greatbeast's way,

Omens of earth, of wood and stone,

is thy message for him alone?”

She cast three stones upon the table, two of common grey, one a black pebble, pitted and marked. The grey stones bounced from the table onto the deck. The black one stayed on the table, close to Razzid.

Closing her eyes, Shekra spoke. “I speak to none but you, Great One.”

The Wearat dismissed his aides. “Leave us.”

Both Mowlag and Jiboree shot hate-laden glances at the vixen. They left the cabinâthough, once outside, they pressed their ears to the closed door in an effort to learn what the Seer had to say.

Shekra went to work with an air of mystery, which she created by sprinkling powder on the table candle. It produced green and black smoke, which swirled around both her and Razzid. The vixen picked up the black, pitted pebble from the table, showing it to the Wearat. “This stone is thee, Razzid, marked by wounds, yet still tough and hard. Watch where it falls and know thy fate, which only the omens can foretell.”

She cast it back onto the table, together with a lot of other bits. Her fertile brain was racing as she studied the jumble of objects.

Razzid dabbed at his bad eye. “So, what do the omens tell ye, Seer?”

Shekra spoke out boldly, knowing what she needed to say. “Death brings death. The old one must be paid for! Look ye, the stone can go any way, but which way to choose, high north or south and east? Which path leads to death, and which to victory? Choose, O Mighty One!”

Razzid seized the vixen's paw in a cruel grip. “If yore tryin' to feed me bilgewater, I'll hang ye from a mast an' skin ye alive, fox. Do I make meself clear?” The Wearat's claws had pierced Shekra's paw, but knowing her life depended on deceiving Razzid, she tried to keep her voice calm and show no pain.

“I am but the messenger, Lord. Slay me an' the knowledge will remain unknown. 'Tis thy decision, sire.”

Razzid snarled as he released his hold. “Then speak. What do the omens mean?”

She began pointing at the way her objects had fallen. “See, the black stone lies between two groups, one facing north, the other southeast. The northern group is mainly stones and shells, all signs of strength and sharp edges.”

Razzid picked something from the small heap. “This is neither stone nor shell. A scrap of dried mossâexplain that t'me if'n ye can.”

Shekra took it from him, blowing it off into the candle flame, where it was shrivelled to ash. She responded promptly. “Nought but the vision of an old wavedog, whose life ended by fire. He was an old chieftain. His spirit must be avenged by the wavedog warriors. Hearken to what I said before. Death brings death. The old one must be paid for.”

Razzid was staring hard at his Seer. “Whose death?”

“My voices say it would be those who slew the old one.”

Razzid sat back in his chair, gazing at the objects on the tabletop. “Wot's that other lot for, the ones ye said were southeast?”

Shekra ran a paw over them. “Wood of trees and soft feathers, Lord. It is not clear, but I feel that is where thy time of victory lies. South, and not too far east, where the sun shines and the weather is fair.”

Razzid leaned forward, his curiosity aroused. “An' where would that be? What place do ye speak of?”

Other books

Along Came a Spider by Kate Serine

Out of the Ice by Ann Turner

Leena's Men by Tessie Bradford

To the Brink and Back: India’s 1991 Story by Jairam Ramesh

Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon?, Vol. 4 by Fujino Omori

Dame of Owls by Belrose, A.M.

Hijos de la mente by Orson Scott Card

Pride by William Wharton

A HIGH STAKES SEDUCTION by JENNIFER LEWIS

Shadow of Sin (The Martin Family) by Kincade, Parker