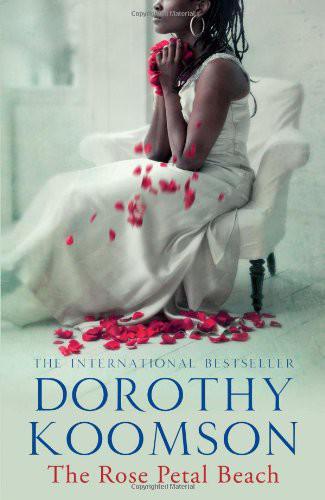

The Rose Petal Beach

The Rose Petal Beach

DOROTHY KOOMSON

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Quercus

55 Baker Street

7th Floor, South Block

London W1U 8EW

Copyright © 2012 Dorothy Koomson

The moral right of Dorothy Koomson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 978 1 78087 496 8

TPB ISBN 978 1 78087 497 5

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78087 498 2

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the authors’ imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Also by Dorothy Koomson

The Cupid Effect

The Chocolate Run

My Best Friend’s Girl

Marshmallows for Breakfast

Goodnight, Beautiful

The Ice Cream Girls

The Woman He Loved Before

For

G & E

Always.

Have you heard the story of The Rose Petal Beach?

The legend of the woman who gave up her whole life for love? She walked around and across the expanse of a deserted island, looking for her beloved who had been lost at sea. Her love was so rare and wondrous, so deep and beautiful and pure, that as she walked her feet were cut by the sharp pebbles on the beach and every drop of blood turned into a rose petal until the beach became a blanket of perfect red petals.

Have you heard the story of The Rose Petal Beach?

Is it a story worth killing for?

This is where my life begins.

Not thirty-six years ago in a hospital in London. Not seventeen years ago when I moved out of my parents’ house to live in a smart but compact bedsit all on my own. Not fourteen years ago when I moved to Brighton. Not twelve years ago when I married my husband. Not even nine years ago when I had my first child. Not seven years ago when I had my second child. My life begins now.

With two burly, uniformed policemen, and one slender plainclothes policewoman standing in my living room, about to arrest my husband.

Five minutes ago

Five minutes ago, Cora, my eight-year-old was on her hands and upside down. She was showing her dad what she had done at school that day in gymnastics. ‘I want to go to the Olympics one day,’ she’d said, her curly hair, folded into two neat plaits, hung on each side of her face while her almost concave stomach strained as her arms trembled with the effort of being upside down for so long. Anansy, our six-year-old, was cuddled up in the corner of the large leather sofa, wearing her pink, brushed-cotton sheep-covered pyjamas, while telling a knock-knock joke.

Scott had finally laid aside his mobile and BlackBerry, both of which he’d been on since he walked in the door, all during dinner, and now in the minutes we had together before the girls were meant to head upstairs to bed. I had been tempted by that point of the evening to calmly walk over to him, take both his phones from his hands and then just as serenely put my heel through the

screen of each of them. Maybe if I broke the link, severed his connection with the office, he would finally leave work and his mind would join his body in the house.

Three minutes ago

Three minutes ago, I was nearest the living-room door, so when the doorbell sounded, followed by a short, loud knock, and I had watched Cora collapse happily – but safely – onto the floor, I went to the blue front door. I wasn’t expecting anyone because everyone we knew would ring first – even the neighbours who would drop by had been ‘trained’ to send a text or call beforehand – no one turned up without notice any more. I’d walked to the door with anxiety on my heels. I’d seen a single magpie sitting on the fence this morning as I washed up after breakfast. Then another of those black and white birds was hopping around the garden when I came in from the school run.

When I opened the door and saw who was standing there, three people who had no real business being on my doorstep, I remembered the salt I spilt at dinner the other night that I’d simply brushed away instead of chucking a pinch of over my shoulder. I thought of the ladder I walked under last month before I even realised I’d done it. I recalled all the cracks in all the pavements I’d been stepping on all my life without a single thought for what they might do, how they might fracture my world at some undefined point in the future.

One minute ago

One minute ago, I thought to myself,

Who’s died?

at exactly the same time the policewoman said, ‘Hello, Mrs Challey. Is your husband in?’

I nodded, and they didn’t wait to be asked in, they entered and went straight for the living room as if they’d been there before, as if they regularly came storming into my life and my home without needing an invitation.

Now

And here we are, in the present, at that moment where my life is about to begin. I know it is about to begin because I can feel the world around me shifting: the air is different; the room that is like any other living room with a sofa and two armchairs, a rug and fireplace, and more pictures of the children than is strictly necessary gracing the walls, feels somehow altered now that these people are here. These

police officers

are here. My life is about to begin because I can feel around me the threads of my reality unravelling, waiting to be re-sewn into a new, unfamiliar tapestry.

‘Mr Scott Challey,’ the policewoman says, her mouth working in an odd fast-slow motion.

Everything has slowed down so it takes me an age to reach Cora and Anansy, to gather them to me, to hold them close while the policewoman speaks. And everything has speeded up, so a second ago the police officers were on the doorstep, now they are taking Scott’s hands and handcuffing him.

The police officer continues, ‘I am arresting you on suspicion of—’ She stops then, pauses at the accusation, the crime that has caused all this. She doesn’t seem the nervous or shy type, but apparently she is the sensitive type. She didn’t seem to notice Cora and Anansy before, but now she stops and shifts her eyes slowly but briefly in their direction before giving Scott a look. An intimate stare from a complete stranger that says they share something that does not need to be spoken; theirs is a connection that does not need words. In response, Scott, whose hands are now ringed by handcuffs, whose body is rigid and upright, nods at her. He is agreeing that she will not voice it in front of the children, he is accepting that she does not need to because he already knows what this is about.

Of course he knows what this is about. In the unfolding nightmare, in the girls clinging to me, in trying to comfort them while attempting to take in everything that is happening, I have missed Scott’s reaction to this: his face is anxious, unsettled – but not

horrified.

He is not responding like the rest of us are because he knew it would happen.

What is going on

?

My fingers are ice-cold as I try to turn Cora’s head into my body; Anansy, who has been terrified of the police since I told her if she stole something from the corner shop again they would come and take her away, has already buried her face in my side, her tears shaking my body.

‘You do not have to say anything,’ the policewoman continues, her eyes focused on my husband. ‘But it will harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned, something which you later rely on in court.’

Will this really get to court? Surely it’s a mistake? Surely.

‘Anything you do say may be given in evidence.’

Scott’s impassive eyes watch her as she speaks.

‘Do you understand these rights as I have read them to you?’ she asks. Scott replies with a half-nod, then his eyes are on me. He knows what is going on, he knew this was coming and he didn’t bother to warn me.

Why?

I think at him.

Why wouldn’t you tell me this was going to happen?

He doesn’t reply to my silent question, instead he looks away, back to the door through which they are about to lead him.

When they have gone, I lower myself onto my knees and pull Cora and Anansy closer to me, bringing them as near as I can to make them feel safe, to make me feel safe, to protect us from the world around us that is unravelling so fast I cannot keep up.

This is where my life begins: with the sound of my daughters crying and the knowledge that my life is coming undone.

Twenty-five years ago

‘What are you here for?’ Scott Challey asked me. I wasn’t the sort of eleven-year-old who was usually to be found waiting in the corridor to see the headmaster, so it wasn’t a surprise that he asked me that.

‘They want me to be on the team for something the school is taking part in for the first time ever. It’s a great honour.’ I was a swot. I had friends who were swots and I was in all the top sets at school. I didn’t mind being a swot, it was just the way things were. ‘What about you?’

‘Same,’ he said, shrugging and looking away.

Scott Challey was not a swot. I knew that about Scott Challey. He was clever and in all the top sets, but he was a Challey, and everyone knew the Challey family. My mum always made sure none of us left the house without an ironed uniform, perfect hair and a bag of books filled with neatly completed homework. Scott’s parents thought their job was done because he was often seen at school and the letters they got home about his behaviour were proof that he went there at all (Mum said).

Whenever Mum or Dad saw one of the Challeys in the street they’d talk about them quietly afterwards but not so quietly we didn’t hear. We knew that they were people you crossed over the road to avoid. But you had to pretend that wasn’t why you crossed the road – they’d do you over if they thought you’d done that. They’d do you over for most things, I’d heard, but definitely for that because, I’d heard, you’d have made them work – i.e. cross the street to get you – to give you a beating, rather than just give you

the beating you might have got from simply walking past them.

I wasn’t sure if I believed that the school would really ask Scott to do this. He was always in trouble. Like, last week in physics Mr McCoy asked Scott to answer a question in front of everyone on the blackboard. When Scott did it, Mr McCoy said that he’d got it wrong. A few people had snickered and Scott, with his eyes all wide and wild and angry, turned around and glared at us all. Everyone stopped laughing straight away. I hadn’t laughed because I knew Scott was right and Mr McCoy was wrong. When someone else put up their hand and said so, Mr McCoy had been embarrassed and said sorry to Scott. But Scott, now with his eyes narrow and mean, said, ‘If you ever do that to me again, I’ll cut your heart out with a spoon and feed it to my dog.’ Mr McCoy didn’t say or do anything. If it’d been anyone else he’d have shouted or sent them to the headmaster’s office but ’cos it was Scott, he knew that Scott would do it if he got him into trouble. And if Scott didn’t do it, he had a family who would.

‘Have the school really asked you to do this thing or are you joking with me?’ I asked him.

‘They really asked me. What would be funny about that?’

I shrugged. ‘I didn’t think you’d want to do it.’

We stood in silence, listening to the voices on the other side of the headmaster’s door. ‘Why did you say that spoon thing to Mr McCoy?’ I asked Scott. I couldn’t help myself. I had to know why someone would say such a thing.

‘He made everyone laugh at me.’

‘Not everyone laughed. I didn’t laugh. Loads of people didn’t laugh. More people didn’t laugh than did laugh.’