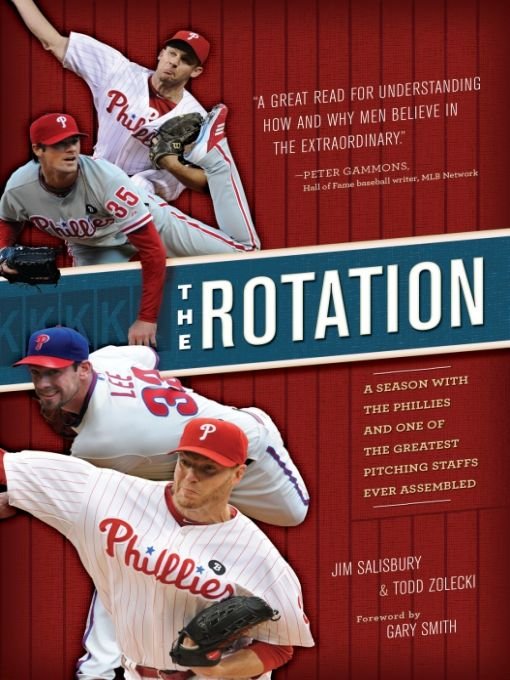

The Rotation

Authors: Jim Salisbury

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

To Mom, Dad and Ann, in appreciation of all your love and support.

âJim Salisbury

Â

Â

Â

To my late grandparents: Roy and Josie Vierzba and Art and Wanda Zolecki. My family's four aces.

âTodd Zolecki

FOREWORD

T

hree decades had flown by since I'd stood inside the locker room of a professional sports team, waiting for athletes to emerge from mysterious hiding places, and with any luck at allâI

thought

âthree decades more would fly, as well. I'd been liberated from that life by an offer to write for a magazine in 1982, and nothing could possibly un-liberate me . . . until something did.

hree decades had flown by since I'd stood inside the locker room of a professional sports team, waiting for athletes to emerge from mysterious hiding places, and with any luck at allâI

thought

âthree decades more would fly, as well. I'd been liberated from that life by an offer to write for a magazine in 1982, and nothing could possibly un-liberate me . . . until something did.

The Rotation.

I watched my hand in surpriseâa few weeks after the Phillies' December 2010 ambush acquisition of Cliff Leeâas it rose to volunteer me to write a series of stories for

Sports Illustrated

that would chronicle the team's historical starting pitching staff and their 2011 season. What would it be like, I wondered through that winter, for a team and a city to send four masters to the mound in succession, over and over again, for sixâand surely sevenâstraight months?

Sports Illustrated

that would chronicle the team's historical starting pitching staff and their 2011 season. What would it be like, I wondered through that winter, for a team and a city to send four masters to the mound in succession, over and over again, for sixâand surely sevenâstraight months?

The Four Aces, the Four Horsemen, the Fab Four: Every Philly writer worth his carpal tunnel had a nickname for them. Mine was The Legion of Arms, for it was a rotation that tickled the child inside an aging sports fan, a foursome that conjured memories of comic-book superheroes joining forces to quell their foes. And, yep, it was easy to feel like a 10-year-old on that February day when the Legion sat down shoulder to shoulder for its season-opening press conference.

But then came the reality of April and May, the hard fact that I'd have to spend long hours standing in a clubhouse, staring at vacant lockers or at players' backs. Back in my old life: back on a

beat

.

beat

.

It's the perfect multilayered word, it occurred to me as I tried to hang in there with the two beat men who authored this bookâJim Salisbury of

CSNPhilly.com

and Todd Zolecki of

MLB.com

.

Beat

, as in the daily round that a cop makes, keeping tabs on the locals.

Beat

, as in the fear of getting beat by the competition that every daily reporter lives in, especially on a media-magnet story like this one.

Beat

, as in how a man feels trying to put in the ridiculous hours that Jim and Todd invested each day to capture this story and this book.

Beat

, as in the rhythmic tick of the clock as we waited for the

Four Aces to materialize and articulate what it feels like to mingle with co-masters and dominate the best hitters in the world.

CSNPhilly.com

and Todd Zolecki of

MLB.com

.

Beat

, as in the daily round that a cop makes, keeping tabs on the locals.

Beat

, as in the fear of getting beat by the competition that every daily reporter lives in, especially on a media-magnet story like this one.

Beat

, as in how a man feels trying to put in the ridiculous hours that Jim and Todd invested each day to capture this story and this book.

Beat

, as in the rhythmic tick of the clock as we waited for the

Four Aces to materialize and articulate what it feels like to mingle with co-masters and dominate the best hitters in the world.

And waited . . . and waited. . . . For the Legion of Arms, just like the superheroes they conjured, were a terse and tight-lipped crew, rationing out a few careful words in their speech bubbles and then hurrying off to ply their craft, to condition their bodies, to recover in their oxygen tent, to ice their arms, to study their foes on video, or to talk hunting and fishing in a back room.

This was a story, I quickly realized, that a writer would have to work at from the edges, widening his scope to teammates, pitching coaches, opponents, broadcasters, fans. Watching Jim and Todd work it relentlessly day after day for far more days than Iâmelding into the media pack around a player one moment and then slipping away the next, following their instincts to poke around alone on the marginsâleft me with a vast respect for what it took to work this beat.

And in the end, no matter how hard they worked it, they were always at the mercy of it. It could end, as it did, with catastrophic suddenness, leaving their audience frozen and wanting only to push the whole thing away.

But the secret of the master fan is not unlike that of the master pitcherâthe secret that Doc Halladay took seven years to learn: It can't be only about outcome. It has to be about each moment along the way. “It's not so much about a distinct finish line,” Doc said one day, when I finally got him to sit down. “I might not always finish everything, but it's the doing of it that matters. That became how I measured myself. It's not so much finishing as it is continually

beating at it

. I had to learn to be in the moment.”

beating at it

. I had to learn to be in the moment.”

The moments. The ones that everyone saw and heard, and the ones that only guys like Salisbury and Zolecki saw and heard. The beating at it, every day of the best season in a Phillies fan's lifeâup 'til the last day. That's what this book offers. You weren't ready for it last November or December, with that last missed note in your ears, but now the thaw's coming fast, and what a shame to lose the beat of that summer song.

Â

âGary Smith, November 2011

INTRODUCTION

J

ohn Kruk has never been afraid to say what's on his mind. Plain. Simple. Organic. If the thought is rattling around the Krukker's brain, it's going to find its way to his tongue and someone else's ears. And if it makes you uncomfortable, well,

Here's Johnny

.

ohn Kruk has never been afraid to say what's on his mind. Plain. Simple. Organic. If the thought is rattling around the Krukker's brain, it's going to find its way to his tongue and someone else's ears. And if it makes you uncomfortable, well,

Here's Johnny

.

“It must be time to talk about my nuts,” Kruk said at the start of a news conference in Clearwater, Florida, in March 1994.

A gaggle of baseball writers winced empathetically when Kruk, then the Phillies first baseman, spoke those words as he rejoined the team after starting treatment for testicular cancer that month.

Seventeen years later, in a news conference at Citizens Bank Park, Kruk was once again saying it like it is. Seated at a dais on the day it was announced that he'd been elected as the 2011 inductee to the team's Wall of Fame, Kruk couldn't resist giving Phillies President David Montgomery a little poke.

“If you had given us a hundred and how much million, we could have been a little better,” Kruk said.

Montgomery smiled sheepishly.

“Things have changed, John,” he said.

Have they ever.

Just ask Scott Rolen. When he played third base for the Phillies from 1996 to 2002, baseball seemed irrelevant in Philadelphia. The team had payrolls that ranked among the lowest in the game, it played in front of an ocean of empty seats at Veterans Stadium, and losing seasons piled up like snowdrifts.

Now?

In 2011, the Phillies' opening-day payroll exceeded $175 million and ranked second only to the payroll of the mighty New York Yankees. They won their fifth straight National League East title, and their streak of sellouts reached 204 regular-season games.

“It's a far cry from hot dog wrappers blowing around the turf at the Vet,” Rolen said during a visit to Citizens Bank Park with the Cincinnati Reds in May 2011. “There were 6,000 people in the stands, we were 30 back, and headed toward 90-something losses. That's not really going on here anymore.

It seems to me the whole Phillies baseball culture has changed. The only similarity I see is the cheesesteaks.”

It seems to me the whole Phillies baseball culture has changed. The only similarity I see is the cheesesteaks.”

Terry Francona has seen the change, too. He was just 37 when he was hired to manage the Phillies in 1997. It was his first big-league manager's job. Francona never kidded himself. He got the job because the Phillies had plummeted to the basement of the National League and getting out of it would be a long, arduous journey, the kind best suited for a young man.

“In those days, the expectation was if we played well, we'd get to .500,” Francona said. “If they were ready to win, they wouldn't have hired me. They would have hired [Jim] Leyland or someone like that.”

Francona was fired after four losing seasons and went on to win the World Series with the Boston Red Sox in 2004 and 2007.

He returned to Philadelphia with the Red Sox in the summer of 2008, and his daughter Alyssa joined him on the trip. She had attended high school in Bucks County when her father managed the Phillies and Padilla's Flotilla was as close as anyone could get to a parade in Philadelphia. Walking around Center City on that June day, Alyssa noticed a change. She felt the electricity that can light up a town when its baseball team is good.

“Dad, it's really different around here,” Alyssa Francona told her father. “Everyone is wearing red.”

And it's not just the fans that are wearing red. Roy Halladay wears red pinstripes now. So does Cliff Lee and Roy Oswalt and, of course, Cole Hamels. Now that, folks, is a starting pitching rotation, the best in baseball, one might say. Whereas Francona once had to send the immortal Calvin Maduro to the minors, and then recall him to be his No. 2 starterâall in the same week in 1997âCharlie Manuel can give the ball to a Cy Young winner, an ERA champ, or a World Series MVP on any given day.

That's why, entering the 2011 season, the Phillies were considered World Series favorites, right there with Francona's Red Sox and the ubiquitous Yankees, baseball's big boys.

It might not have worked out that way, with the Phillies and Red Sox playing in the World Series, but it sure was fun to fantasize about as the season approached.

“They've done a terrific job,” Francona said of the Phils in March 2011. “They're in a different place now. They have the ballpark. They're a big market. And people are hungry for a good team. Those people deserve a team like that. It's good for baseball.”

Francona paused that March day as images of the Phillies' rotation

passed through his mind.

passed through his mind.

“I don't know if I'd want to be in the National League facing those pitchers every day, but they've got a good thing going,” he said.

On August 15, 2011, Jim Thome made big baseball news when he became just the eighth player to hit 600 big-league home runs. He did it while wearing a Minnesota Twins uniform. Surely, there would never be a bad time to give one of baseball's all-time good guys a tip of the cap for this special accomplishment, but that's not why we bring up his name here.We mention Thome because one could make a case that baseball began to matter again in Philadelphia in December 2002 when Thome, baseball's premier free agent that winter, decided to sign with the Phillies, who had smartly targeted him to be the ticket-selling booster shot of excitement the team needed with a new stadium on the way.

Other books

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

Whiskey Tribute: A Trident Security Series Novella - Book 5.5 by Samantha A. Cole

Oliver Twisted (An Ivy Meadows Mystery Book 3) by Cindy Brown

Burn by R.J. Lewis

Hope's Angel by Fifield, Rosemary

Jubilate by Michael Arditti

Levi (Prairie Grooms, Book Five) by Morgan, Kit

Paul Newman by Shawn Levy

Major Misconduct (Aces Hockey #1) by Kelly Jamieson

Beauty and the Boss (Modern Fairytales) by Diane Alberts