The Royal Stuarts: A History of the Family That Shaped Britain

Read The Royal Stuarts: A History of the Family That Shaped Britain Online

Authors: Allan Massie

For Claudia and Matt

Contents

List of Illustrations

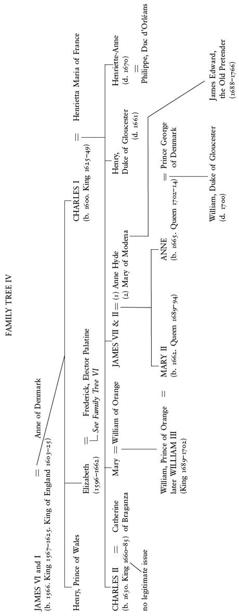

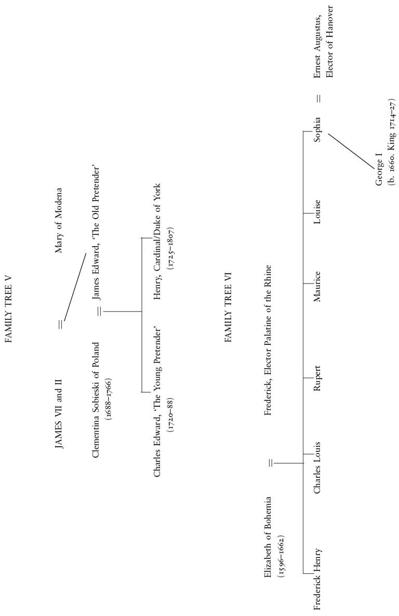

The Genealogy of the House of Stuart

Chapter 1. The Stewards: Origins in Legend and History

Chapter 2. Robert II (1371–90): The First Stewart King

Chapter 3. Robert III (1390–1406): A Troubled Reign

Chapter 4. James I (1406–37): The Poet-King

Chapter 5. James II (1437–60): A Quick-Tempered King

Chapter 6. James III (1460–88): A Study in Failure

Chapter 7. James IV (1488–1513): The Flower of the Scottish Renaissance

Chapter 8. James V (1513–42): People’s King or Tyrant?

Chapter 9. Mary (1542–67): Scotland’s Tragic Queen

Chapter 10. James VI and I (1567–1625): The King as Survivor

Chapter 11. Charles I (1625–49): The Martyr King

Chapter 12. The Interregnum and the Scattered Family (1649–60)

Chapter 13. Charles II (1649–85): A Merry and Cynical Monarch

Chapter 14. James VII and II (1685–88): Author of His Own Tragedy

Chapter 15. William III (1689–1702) and Mary II (1689–94): Revolution Settlement and Dutch Rule

Chapter 16. Anne (1702–14): End of an Old Song

Chapter 17. James VIII and III: Jacobites

Prologue

It was between ten and eleven o’clock on a July morning in 1685. The condemned man mounted the scaffold with a firmer step than many had expected.

A century and a half later, Macaulay

1

would describe the scene with that relish in executions characteristic of Victorian historians and novelists:

Tower Hill was covered up to the chimney tops with an innumerable multitude of gazers who, in awful silence, broken only by sighs and the noise of weeping, listened for the last accents of the darling of the people. ‘I shall say little,’ he began. ‘I come here, not to speak but to die. I die a Protestant of the Church of England.’ The Bishops interrupted him and told him that, unless he acknowledged resistance [to the royal authority] to be sinful, he was no member of their church. But it was in vain that the prelates implored him to address a few words to the soldiers and the people on the duty of obedience to the government. ‘I will make no speeches,’ he exclaimed. He then accosted John Ketch the executioner. ‘Here,’ said the Duke, ‘are six guineas for you. Do not hack me as you did my Lord Russell. I have heard that you struck him three or four times. My servant will give you more gold if you do the work well.’ He then undressed, felt the edge of the axe, expressed some concern that it was not sharp enough, and laid his head on the block. The executioner addressed himself to his office. But he had been disconcerted by what the Duke said. The first blow inflicted only a slight wound. The Duke struggled, rose from the block and looked reproachfully at the executioner. The head sank down once more. The stroke was repeated again and again, but still the head was not severed, and the body continued to move. Yells of rage and horror rose from the crowd. Ketch flung down the axe with a curse. ‘I cannot do it,’ he said, ‘my heart fails me.’ ‘Take up the axe, man,’ cried the Sheriff. ‘Fling him over the rails,’ roared the mob. At length the axe was taken up. Two more blows extinguished the last remnants of life; but a knife was used to separate the head from the shoulders. The crowd was wrought up to such an ecstasy of rage that the executioner was in danger of being torn to pieces, and was conveyed away under a strong guard. In the meantime many handkerchiefs were dipped in the Duke’s blood, for by a large part of the multitude he was regarded as a martyr who had died for the Protestant religion. The head and body were placed in a coffin covered with black velvet, and were laid privately under the communion table of Saint Peter’s Chapel in the Tower. In truth there is no sadder spot than that little cemetery. Death is there associated…with whatever is darkest in human nature and human destiny, with the savage triumph of implacable enemies, with the inconstancy, the ingratitude, the cowardice, of friends, with all the miseries of fallen greatness and of blighted fame.

Thus, incomparably, from the decent security of his study, the great Whig historian described the botched piece of butchery that ended the life of the Duke of Monmouth and Buccleuch. It was to be the last execution of a royal duke, a king’s son, in Britain. Kings, queens, dukes, earls and countesses, all royal, had gone to the block before him, suffered on Tower Green, in Fotheringay Castle, outside the Palace of Whitehall and in various castle courtyards in England and Scotland. But he would be the last, and, his reputation as ‘the Protestant Duke’ having faded, is now perhaps the least remembered.

Some would hold that poor Monmouth was not truly royal, for he was the illegitimate son of Charles II and a Welsh girl called Lucy Walter, born in 1650 while the King was in exile. But Charles acknowledged him as his son, while denying that he had ever been married to Lucy. The story will be told in full in its proper place. Suffice to say now that many believed that there had been a marriage, and Monmouth was almost certainly one of them.

Being illegitimate, he never bore the royal name of Stuart. As a young man he was known as Mr Crofts, taking the name from a gentleman appointed his guardian, and then, after his marriage to Anne Scott, Lady of Buccleuch in the Scottish Borders, he assumed his wife’s family name. He was Charles’s favourite among his numerous bastards, a young man of grace and charm.

Anthony Hamilton, author of the memoirs of his brother-in-law, the Comte de Grammont,

2

left this description of the Duke:

His figure and the exterior graces of his person were such that nature never formed anything more perfect. His face was extremely handsome; and yet it was a manly face, neither inanimate nor effeminate; each feature having a beauty and peculiar delicacy; he had a wonderful genius for every form of exercise, an engaging aspect, and an air of grandeur. The astonishing beauty of his outward form caused universal admiration. Those who were before looked on as handsome were now entirely forgotten at court; and all the gay and beautiful of the fair sex were at his devotion. He was particularly beloved by the King, but the universal terror of husbands and lovers.

However, Hamilton adds, while Monmouth ‘possessed every personal advantage, he was greatly deficient in mental accomplishments; he had no sentiments but such as others inspired in him, and those who insinuated themselves into his friendship took care to inspire him with none but such as were pernicious. He appeared to be rash in his undertakings, irresolute in the execution, and dejected in his misfortunes.’