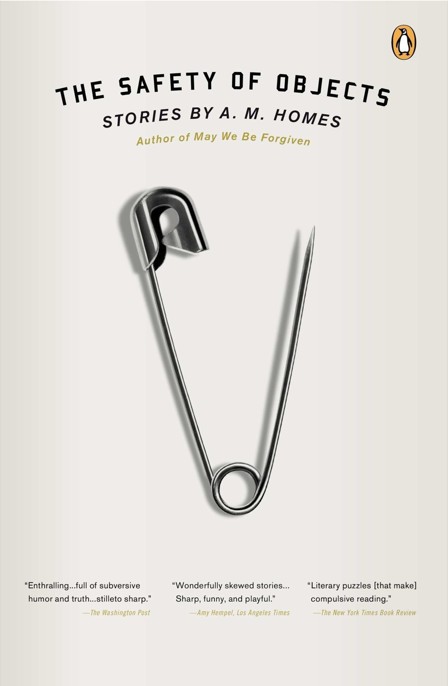

The Safety of Objects: Stories

Read The Safety of Objects: Stories Online

Authors: A. M. Homes

Tags: #Fiction, #Short Stories (Single Author)

Praise for

The Safety of Objects:

Stories

by A. M. Homes

“Sharp, funny, and playful . . . Homes is confident and consistent in her odd departures from life as we know it, sustaining credibility by getting details right. A fully engaged imagination [is] at work—and play.”

—Amy Hempel,

The Los Angeles Times

“Set in a world filled with edges to topple from, [

The Safety of Objects

] is permeated by the bizarre. . . . The unexpected emerges from the story itself, startling and unexpectedly right.”

—

The Cleveland Plain Dealer

“A. M. Homes finds mystery without special effects or exotic underbellies. We get a tour through the action adventure of everyday fantasies. Many of Homes’s characters lead two lives, one on God’s most conventional little acre, one in some alternate universe.”

—

Mirabella

“A collection of deft, off-center stories about bizarre situations and the people unwittingly thrust into them . . .

The Safety of Objects

takes us on a

Twilight Zone

tour of everyday life. After it’s over, the reader may have lost some sense of boundaries, but that’s all to the good. That’s what keeps life, and literature, fresh.”

—

Detroit Free Press

“Homes’s surprises proceed out of a stranger, surrealistic fictional world. . . . One way or another, there’s no place like Homes and her stories.”

—

San Francisco Examiner

“Homes’s vision may be relentlessly grim, but it’s undeniably vivid and uncomfortingly familiar. . . . [H]er singular voice has deftly chronicled a suburban collage of marriage, mortgages and, lurking just beneath the veneer, madness.”

—

Rocky Mountain News

“A. M. Homes’s provocative and funny and sometimes very sad takes on contemporary suburban life impressed me enormously. The more bizarre things get, the more impressed one is by A. M. Homes’s skills as a realist, a portraitist of contemporary life at its more perverse.”

—David Leavitt

“These stories are remarkable. They are awesomely well written. In the sense of arousing fear and wonder in the reader they entertain, but what they principally bring us is a sense of recognition. . . . Here are all the things that even today, even in our frank outspoken times, we don’t talk about. We think of them punishingly in sleepless nights.”

—Ruth Rendell

“An unnerving glimpse through the windows of other people’s lives. A. M. Homes is a provocative and eloquent writer, and her vision of the way we live now is anything but safe.”

—Meg Wolitzer

“A. M. Homes’s fresh and determined young voice emerges with vigor in this engaging collection of stories. You know the world will hear more of her.”

—Thomas Keneally

“A. M. Homes has a real gift for using a single, sharp tool to make (or suggest, perhaps) an astute general observation. With little she makes much, a trait I much admire in these days of profuse and prolix novels.”

—Doris Grumbach

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE SAFETY OF OBJECTS

A. M. Homes is the author of the memoir

The Mistress’s Daughter

and the novels

May We Be Forgiven

,

This Book Will Save Your Life

,

Music for Torching

,

The End of Alice

,

In a Country of Mothers

, and

Jack

, as well as the story collection

Things You Should Know

and the travel book

Los Angeles: People, Places, and the Castle on the Hill.

Her books have been translated into twenty-two languages. The recipient of numerous awards, she has published fiction and essays in

The New Yorker

,

Granta

,

Harper’s Magazine

,

McSweeney’s

,

One Story

,

The New York Times

and

Vanity Fair

, where she is a contributing editor. She lives in New York City.

The Safety

of Objects

STORIES BY

A. M. Homes

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa), Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue,

Parktown North 2193, South Africa

Penguin China, B7 Jiaming Center, 27 East Third Ring Road North, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 1990

Reprinted by arrangement with W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Published in Penguin Books 2013

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © A. M. Homes, 1990

All rights reserved

Acknowledgment is made to the periodicals in which some of these stories originally appeared: “Looking for Johnny,” The I of It,” and “A Real Doll” in

Christopher Street

; “Yours Truly” and “Esther in the Night” in

Story

; “Chunky in Heat” in

Between C & D

; “Slumber Party” in

New York Woman

.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS

:

Homes, A. M.

The safety of objects / by A. M. Homes.

p. cm.

I. Title.

ISBN 978-0-393-02884-3 (hc.)

ISBN 978-0-14-312270-8 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-101-59041-6 (epub)

PS3558.0448S2 1990

813'.54—dc20 90-30579

Designed by Alice Sorensen

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

The author wishes to thank Randall Kenan, Neil B. Olson, the Corporation of Yaddo, and the Department of English/Creative Writing at New York University for their support.

To Eric and Alice

Adults Alone

Elaine takes the boys to Florida and drops them off like they’re dry cleaning.

“See you in ten days,” she says as they wave good-bye in the American terminal. “Be nice!”

She kisses her mother-in-law’s cheek and, feeling the rough skin against her own, thinks of this woman literally as her husband’s genetic map, down to the beard.

“Go,” her mother-in-law says, pushing her toward the gate.

It is the first time she’s left her children like that. She gets back onto the plane thinking there’s something wrong with her, that she should have a better reason or a better vacation plan, Europe not Westchester.

Paul is waiting at the airport. He’s been there all day. After dropping them off this morning, he took over the west end of the lounge and spent the day there working. She knows because he paged her at Miami International to remind her to bring oranges home.

He seems younger than she remembers. His eyes are glowing and he looks a little bit like Charlie Manson did before he let himself go. Elaine is sure he’s been smoking dope again. She imagines Paul locking himself in an airport bathroom stall with his smokeless pipe and some guy who got bumped off a flight to L.A.

She wonders why he doesn’t find it strange, pressing himself into a tiny metal cabinet with a total stranger. He once told her that whenever he got stoned in a bathroom with another guy it gave him a hard-on, and he was never sure if it was the dope or the other man.

She can’t believe that in all these years he’s never been busted. She used to wish it would happen; she thought it would straighten him out.

“Let’s go home,” Elaine says.

“We don’t have to go home, we can go anywhere. We can. . . ” He winks at her.

“I’m tired,” Elaine says.

They drive home silently. The car is so new that it doesn’t make any noises. Paul pulls carefully into the driveway. Branches from trees surrounding the house scrape across the car. Elaine thinks of campfire horror stories about men with hooks for arms and women buried alive with long fingernails poking through the dirt.

“Got to cut those branches back,” Paul says and then they are silent.

Paul follows her up the steps, talking about the steps. “If we’re going to paint them, we should go ahead and do it before it snows.”

“Maybe tomorrow,” she says, but honestly she doesn’t want to do anything else to the house. She’s given up on it. It’s too much work.

She feels like she’s been having an extramarital relationship with their home. It isn’t even an affair, an affair sounds too nice, too good. As far as she’s concerned a house should be like a self-cleaning oven; it should take care of itself.

The last time she was happy with the house was the day before they moved in, when the floors had just been done, when it was big and empty, and they hadn’t paid for it yet.

Elaine pushes open the front door.

“I wish you’d remember to lock the door,” she says. In the city you never forgot to lock the door.”

It is dark inside. Elaine stands in the front hall, trying to remember where the light switch is. In the six months they’ve lived there, she and Paul have never been alone in the house. It’s nice, she thinks, still feeling the wall for the switch. She turns on all the lights and begins picking up things, Daniel’s clothing, Sammy’s toys. She straightens the pillows on the sofa and goes upstairs to take a bath. The phone rings and Paul answers it. She falls asleep hearing the sound of voices softly talking, thinking Paul is a good father; he is down the hall, reading a story to Sammy.

As usual they both wake between six-thirty and seven, listening for the children. They are alone together, trapped in their bed. They don’t have to get up. They don’t have to go anywhere. They are on vacation.

Eventually, between seven-thirty and quarter-to-eight, when there is no more getting around it, she looks at him. He is balding. She thinks she can actually see his hairline receding, follicle by follicle. He has told her that he can feel it. He says his whole head feels different; it tingles, it gets chilled easily, it just isn’t the way it used to be. She thinks about herself. Her face is caving in. She has circles and bags and all kinds of things around her eyes. Last week she spent forty dollars on lotion to cover it all up.

When she comes downstairs, he has already eaten breakfast and lunch.

“Maybe we should go to a movie later?” he says.

Paul doesn’t really mean they should go to a movie; he means they should make a time to be together, in some way or another. Usually they have to get a sitter for this.

“Pick you up around four,” he says.

“Does that mean you’re taking the car? I have things to do.”

“We can go together,” he says.

In his fantasy about suburban life the whole family is always in the car together, going places, singing songs, eating McDonald’s. He loves it when they pull up in front of a store and he goes in while she waits in the car for as long as it takes.

“Forget it,” she says.

* * *

Late in the afternoon, Paul comes into the bedroom where Elaine is resting.

“I brought you something,” he says, handing her a porno tape he rented in town.

“For me?” she says.

She can’t imagine that he brought this for her. If he was going to bring her a present she’d like flowers, a scarf, even a record. Porno is not a gift.

He puts the tape in the VCR. They are so used to each other that it doesn’t take long, and after a short nap they decide to actually go to the movies.

The marquee isn’t lit and Elaine has to put on Paul’s glasses in order to see what’s playing. He says something about smoking a joint in the theater, but she reminds him that they both have professional reputations.

“You never know where your clients might be,” she says. “Besides,” she whispers in his ear, “this isn’t Manhattan.”

She puts her hand on his crotch and squeezes. She knows he likes it when she does things like that in public places.

In the darkness of the theater they fall in love. They fall in love not so much with each other, that’s history, but in love with the idea of being in love, of liking someone that much. She puts her head on his shoulder and he doesn’t say anything about it hurting his tennis arm.

After the movie, they walk down the main street. Paul walks with his hands in his pockets and Elaine keeps her arms wrapped tightly around her chest like she’s protecting herself from something. It’s as if in the dark theater they swore they’d be in love for the entire week, but outside in the fresh air, neither is sure it’s viable.

Elaine and Paul cut across the street and go into the only restaurant in town where they can both eat without getting sick. Paul orders a bottle of wine. He orders fettuccine alfredo without checking with Elaine. She doesn’t say anything about his cholesterol. It’s part of their love agreement. They are for the moment Siamese twins separated. They are off-duty parole officers. They are free. Their sons are in Florida being overfed by his mother.

* * *

In the car on the way home they smoke two joints. She tells Paul to drive by the sound before going back to the house. He parks at the edge of the water, turns off the engine, and they sit looking out, across to whatever it is that’s out there, maybe Connecticut.

“Did you think we’d ever be here, like this?” Elaine asks.

“Here like what?”

“Here, in a house, with a station wagon?”

A light flashes across their car, and instead of going on it freezes on Elaine and Paul. There is a knock on Paul’s window and the flashlight shines in.

“Roll down your window, sir?” the police officer says. “Can I help you? Are you looking for something?”

“Just taking in the view,” Paul says.

Elaine thinks they’re being busted, the cop smells the dope. She can’t believe she’s in the car and this is happening, now, to her. She hardly ever gets stoned.

Even though it’s early October, Paul is beginning to sweat. Elaine thinks he’ll turn them in. He’s reminding her of Dagwood Bumstead.

“We just moved here six months ago,” Elaine says.

It’s always her job to take care of things. To deal. If they are arrested, they will have to move, immediately, before the boys come home. There will be a picture of her on the front page of the local paper.

NEWCOMER UP IN SMOKE

.

“Do you have any identification? May I see your license, sir?”

The cop looks like he’s twelve years old. If he ever shaves it’s not because he has to, but because it makes him feel older.

“Is this your current address?”

“No, we live here at three-four-three-three Maplerock Terrace,” Elaine says.

She smiles at the cop. He doesn’t ask for her license. She’s the wife.

The cop’s whole head is inside the car, but he doesn’t seem to smell anything. Elaine decides that either he’s retarded or has a serious sinus problem.

“You’re new here,” he says.

“That’s right. I’m even a member of the newcomers club, meets once a month,” Elaine says, determined to keep them out of jail.

“Well,” the cop says. “Why don’t you go on home now.”

“We were just taking in the view,” Paul says, nodding toward the sound.

“We don’t do that here, sir,” the cop says. “Have a good evening, sir,” the cop says.

He turns off his flashlight and walks back to the squad car.

Paul doesn’t start the car right away. He doesn’t seem able to. He’s covered with a slimy film of sweat. His skin is glow-in-the-dark white.

“Are you in pain?” Elaine asks.

She turns on the map light so she can get a better look at him.

“Are you having a heart attack?”

She wishes she hadn’t let him order the fettuccine.

“Should I take you to the hospital?”

“Drive home?” he says.

She opens her door and goes around to the other side. The cop is parked down the block, lights off, watching them.

Paul crosses over inside the car. His legs get stuck on the gear shift and it is a few minutes before Elaine can get in. She stands in the street, waiting. She thinks about what would happen in an emergency, if Paul really had to stand up to something, a burglar maybe.

* * *

During the night Paul’s stomach starts in and toxic clouds billow silently from his sleeping body. Elaine goes into Sammy’s room and buries herself among the stuffed animals, using the big bear for a pillow and a husband.

At around seven Paul wakes Elaine by trying to fit himself next to her in the twin bed.

“You smelled terrible,” she says.

“Why did you let me have the fettuccine?”

She doesn’t say anything. It’s too complicated. She let him eat it because she doesn’t like him and doesn’t care what he does and wishes he would die soon. She let him eat it because she loves him and can’t deny him his pleasures and is determined not to act like his mother.

He starts to make love to her.

“Not here,” she says, thinking it’s an incredibly perverted thing to do in their child’s bed.

He stops and curls next to her. She rolls in toward the wall, pulling the Mickey Mouse blanket up over her head. Without the children, with nothing absolutely required of her, she is exhausted. She is more tired than she ever remembers being.

She dreams that her children have been attacked by a shark. She hears her mother-in-law telling her the story, long-distance.

“They’re fine, that’s the most important thing. In the history of Miami Beach, it never happened before. Sammy was lying at the edge of the water, not really even in the water, and a shark, a very small shark, washed up on top of him. And Daniel, what a big boy, what a man, reached down and pulled the shark off Sammy, but then the shark got Daniel by the arm. It wasn’t a big shark. It must have been dying because why else was it on the beach? Daniel just shook it off. No skin broken. It’s here now, in the bathtub. The boys want to have it stuffed. I said it’s up to you. You’re the mother.”

* * *

At noon Elaine gets out of bed and pulls on the same clothing she wore yesterday. She doesn’t bother to brush her teeth. She isn’t going to run into anyone she has to talk to. Elaine takes the car to the grocery store. She sits in the parking lot staring at the store. She hates it but figures that since she’s already there, she’ll be a good sport, she’ll run in.

Elaine picks out items that are strictly for adults only, foods her children would never let her buy: smelly cheese, pâté, crackers with seeds, wine. It adds up to thirty-nine dollars and somehow fits into one bag.

“My mother called,” Paul says as she walks into the house.

He is on a ladder in the hallway, changing a bulb that burned out three months ago.

“Is everything all right?” she asks, thinking of the shark dream.

“Sammy misses you. They’ll call back.”

She crosses under the ladder and goes into the kitchen.

“Bad luck, under the ladder,” he says.

She makes herself a huge plate of food, takes a bottle of wine, and crosses back under the ladder on her way upstairs.

“Are you planning to share?”

She doesn’t answer him. She knows he can’t imagine her eating all that. She hates food, and yet she is hungry; she is so hungry that she can’t wait to get upstairs where she can be alone with the food, where she can dig in without an audience.

“I’m changing the bulb, didn’t you notice?”

She knows she’s supposed to think he’s wonderful for finally doing something. But as far as she’s concerned, he’s wasting time. Elaine throws a grape at him. It hits his chest and falls into his shirt.

“Grapes cost three dollars a pound,” he says. “I thought we agreed not to buy them. The boys just squish them between their fingers and leave them on the table.”

“The boys are away,” she says, and continues up the stairs.

She sits in the middle of their bed with her plate. Something is missing: olives, onions, garnishes. She carries the plate back downstairs.

Paul is sitting in the chair in front of the TV, in broad daylight, with a glass of Hawaiian Punch in his hand. He looks like a demented version of the suburban man, the Playboy man, the man in his castle.