The Science of Language (32 page)

Read The Science of Language Online

Authors: Noam Chomsky

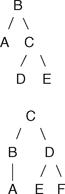

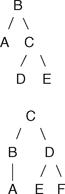

To understand c-command and a bit of its roles, consider the following hierarchical linguistic structures:

Now introduce the notion of domination, which is intuitively defined over a hierarchical structure of the sort illustrated. In the first figure above, B immediately dominates A and C, B dominates A in the second. Given this intuitive notion, we can now define c-command this way: X c-commands Y if X does not immediately dominate Y or vice versa

and

the first branching node that dominates X also dominates Y. Thus for the first structure above, A c-commands C, D, and E; B does not c-command anything; C c-commands A; D c-commands E; E c-commands D. And for the second, A c-commands D, E, and F.

and

the first branching node that dominates X also dominates Y. Thus for the first structure above, A c-commands C, D, and E; B does not c-command anything; C c-commands A; D c-commands E; E c-commands D. And for the second, A c-commands D, E, and F.

C-command figures in several central linguistic principles, principles that govern the ways in which sentences and the expressions within them can/must be interpreted/understood. One example is found in “

binding theory,” a set of three principles that for all natural languages describes the syntactically determined binding/co-indexing properties of referential expressions, pronouns, and anaphors. An example of an anaphor in English is a reflexive pronoun, such as

herself

. . .

Harriet washed herself

. Clearly,

herself

must be coreferential with

Harriet

, unlike

Harriet washed her

, where

her

clearly cannot be used/understood to corefer with

Harriet

. An informal way to express this is to say that anaphors must be bound within the

minimal

(smallest) domain containing a subject:

Harriet watched Mary wash herself

is fine, but

herself

must be used to corefer with

Mary

, not

Harriet

. A more formal and theoretically useful way – more useful because c-command plays a central role elsewhere too, and in capturing a linguistic universal allows the theoretician to consolidate – is this: an anaphor's antecedent must c-command it. This is “Condition A” of binding theory.

binding theory,” a set of three principles that for all natural languages describes the syntactically determined binding/co-indexing properties of referential expressions, pronouns, and anaphors. An example of an anaphor in English is a reflexive pronoun, such as

herself

. . .

Harriet washed herself

. Clearly,

herself

must be coreferential with

Harriet

, unlike

Harriet washed her

, where

her

clearly cannot be used/understood to corefer with

Harriet

. An informal way to express this is to say that anaphors must be bound within the

minimal

(smallest) domain containing a subject:

Harriet watched Mary wash herself

is fine, but

herself

must be used to corefer with

Mary

, not

Harriet

. A more formal and theoretically useful way – more useful because c-command plays a central role elsewhere too, and in capturing a linguistic universal allows the theoretician to consolidate – is this: an anaphor's antecedent must c-command it. This is “Condition A” of binding theory.

The Minimalist Program illuminates why c-command plays an important role, and how it does so. The minimalist picture of sentence derivation/computation, at least on certain assumptions that are rather technical and that

cannot be discussed here, offers an elegant picture of c-command and how it comes to have the properties it does. Minimalism treats a

derivation as a matter of Merge – either internal or external. Consider an internal merge; it places an element that is already a part of a derivation “at an edge” – in effect, at the front of a set in which it leaves a copy [or a copy of A is put at the edge . . .]. For example,{A {B. . . {A. . .}}}. This portrays c-command in a nutshell: the ‘fronted’ element c-commands all the other elements, on the assumption – one that is well motivated – that the copy/copies of A will not be pronounced. C-command becomes precedence – being a ‘later’ Merge. For some fairly non-technical discussion, see Boeckx (

2006

).

cannot be discussed here, offers an elegant picture of c-command and how it comes to have the properties it does. Minimalism treats a

derivation as a matter of Merge – either internal or external. Consider an internal merge; it places an element that is already a part of a derivation “at an edge” – in effect, at the front of a set in which it leaves a copy [or a copy of A is put at the edge . . .]. For example,{A {B. . . {A. . .}}}. This portrays c-command in a nutshell: the ‘fronted’ element c-commands all the other elements, on the assumption – one that is well motivated – that the copy/copies of A will not be pronounced. C-command becomes precedence – being a ‘later’ Merge. For some fairly non-technical discussion, see Boeckx (

2006

).

Minimalist efforts to eliminate ‘artifacts’ from theories of grammar suggest that one should not take c-command as a primitive of linguistic theory. It is a useful descriptive tool but – as the paragraph above suggests – it might be eliminable in favor of features of

internal and external Merge. As Chomsky (

2008

) argues, Condition C and Condition A of binding theory can be dealt with in this way. One point of the Minimalist Program is, of course, to eliminate items that cannot be justified by “principled explanation” and to aim toward conceiving of the language system as perfect. The discussion above illustrates some progress in that

regard.

internal and external Merge. As Chomsky (

2008

) argues, Condition C and Condition A of binding theory can be dealt with in this way. One point of the Minimalist Program is, of course, to eliminate items that cannot be justified by “principled explanation” and to aim toward conceiving of the language system as perfect. The discussion above illustrates some progress in that

regard.

Variation, parameters, and canalization

The naturalistic theory of language must speak not only to ways in which languages are the same (principles, UG), but also to ways in which languages can differ. A descriptively and explanatorily adequate naturalistic theory of language should have the resources available to it to describe any given I-language and, to do that, it must have the theoretical resources to describe any biophysically possible I-language.

Some differences between I-languages are, however, beyond the reach of naturalistic study. People can and do differ in how they pair ‘sound’ information with ‘meaning’ in their lexicons (Chomsky

2000

). To one person, the sound “arthritis” is associated with JOINT AILMENT; to another, perhaps with LIMB DISEASE (or with whatever else a person understands the sound “arthritis” to mean). These pairings are from the point of view of the natural scientist simply irrelevant; they are examples of what Chomsky calls “Saussurean arbitrariness.” Natural science must ignore the pairings because they are conventional, social, or idiosyncratic. They are not due to natural factors, to the way(s) that nature “cuts things at the joints,” paraphrasing Plato. This is not to say that these differences are unimportant for practical purposes: if you want to communicate easily with another person, your pairings better overlap the other person's. It is only to say that the pairings are a matter of choice, not nature, and so irrelevant to a natural science of language.

2000

). To one person, the sound “arthritis” is associated with JOINT AILMENT; to another, perhaps with LIMB DISEASE (or with whatever else a person understands the sound “arthritis” to mean). These pairings are from the point of view of the natural scientist simply irrelevant; they are examples of what Chomsky calls “Saussurean arbitrariness.” Natural science must ignore the pairings because they are conventional, social, or idiosyncratic. They are not due to natural factors, to the way(s) that nature “cuts things at the joints,” paraphrasing Plato. This is not to say that these differences are unimportant for practical purposes: if you want to communicate easily with another person, your pairings better overlap the other person's. It is only to say that the pairings are a matter of choice, not nature, and so irrelevant to a natural science of language.

To put the point in another way, the natural science of language focuses on what is innate. So it focuses on the lexicon, but not on the pairings found in a particular person's head. It focuses (or should) on the sounds and meanings that are available for expression – that is, for pairing in the lexicon, and for appearance at relevant interfaces. These sounds and meanings are innate in that they are built into whatever kinds of acquisition mechanisms make them available, at the same time limiting the ones that are available, for a mechanism can only yield what it can. Its possible variants are built into it.

There seem to be limits on the sounds that are available within any specific natural language. Chomsky remarks (

1988

) that while “strid” could be a sound in English, it cannot in Arabic. On the other hand, “bnid” is available in Arabic, but not in English. To deal with what is or is not available in the

class of I-languages that are sometimes called “natural languages,” one appeals to parameters. Parameters, it is assumed, are built into the acquisition mechanisms. They might be biological in nature (built into the genome), or due to other factors, those that Chomsky labels “third factor” contributors to acquisition/growth mechanisms.

1988

) that while “strid” could be a sound in English, it cannot in Arabic. On the other hand, “bnid” is available in Arabic, but not in English. To deal with what is or is not available in the

class of I-languages that are sometimes called “natural languages,” one appeals to parameters. Parameters, it is assumed, are built into the acquisition mechanisms. They might be biological in nature (built into the genome), or due to other factors, those that Chomsky labels “third factor” contributors to acquisition/growth mechanisms.

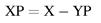

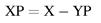

Far more attention is paid, however, to the parametric differences in ‘narrow syntax,’ to the different ways available for different natural languages (taken here to be classes of I-languages that are structurally similar) to carry out computations. The conception of parameters and their settings has changed since their introduction with the

Principles and Parameters program in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The original conception – and the one that is easiest to describe and illustrate, so that it is useful for explication in texts like this – held that a parameter is an option available in a linguistic principle (a universal ‘rule’). The “

head” parameter is often mentioned. Beyond lexical features and morphemes, the next most basic units of language are phrases. Phrases are understood to consist of a “head” (a lexical item of a specific category, such as N(oun) or V(erb)) and a “complement” which may be another phrase, such as an adjective/adverb phrase. So one might have a Verb Phrase (VP) amounting to

wash slowly

with a V head followed by an adjectival/adverbial complement, an AP reduced to an A. Rather, that is what you would find in English and many other languages. That is because these are “

head first” languages. In others, such as Japanese or Miskito, the order is reversed. Phrases in these languages also have the structure of a head and a complement, but in these languages, the head appears after the complement. Stating the relevant parameter with options included ‘in’ the parameter, it is:

Principles and Parameters program in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The original conception – and the one that is easiest to describe and illustrate, so that it is useful for explication in texts like this – held that a parameter is an option available in a linguistic principle (a universal ‘rule’). The “

head” parameter is often mentioned. Beyond lexical features and morphemes, the next most basic units of language are phrases. Phrases are understood to consist of a “head” (a lexical item of a specific category, such as N(oun) or V(erb)) and a “complement” which may be another phrase, such as an adjective/adverb phrase. So one might have a Verb Phrase (VP) amounting to

wash slowly

with a V head followed by an adjectival/adverbial complement, an AP reduced to an A. Rather, that is what you would find in English and many other languages. That is because these are “

head first” languages. In others, such as Japanese or Miskito, the order is reversed. Phrases in these languages also have the structure of a head and a complement, but in these languages, the head appears after the complement. Stating the relevant parameter with options included ‘in’ the parameter, it is:

P is ‘phrase,’ and the variables X and Y can have the values N, V, or A, and (on earlier views) P (for pre/postposition). The dash (–) is unordered, allowing X to be before YP, or YP to be before X. The dash allows for initial (X-YP) or final (YP-X) heads. In this sense, the parametric options are ‘in’ the formal statement of the “phrase principle.”

More recent discussion of parameters reconceives them in two significantly different ways. One is due to the suggestion that all parametric differences between languages are found in what are called “functional categories.” A functional category

amounts to any category of (oversimplifying here) lexical item that indicates a difference not in content, but in the ‘shape’ of a grammar. Relevant differences arise in verb phrase structure, in complementation (

that

. . .,

which

. . .), and in the forms of ‘auxiliary’ operation that determine subject–verb agreement, and the like. A functional category might be expressed in different languages in different ways. In English, some prepositions (such as

of

) express a grammatical or functional difference,

others (such as

under

) a lexical content one. By assuming that some lexical items express functional categories or grammatical information alone (and not lexical ‘content’ information), and by assuming further that parametric differences between languages are different ways the language faculty has available to it to meet the “output conditions” set by the systems with which it must ‘communicate’ at its interfaces, it came to be assumed that parametric differences are lodged in “function words,” rather than in the principles themselves, as was assumed in the early account.

amounts to any category of (oversimplifying here) lexical item that indicates a difference not in content, but in the ‘shape’ of a grammar. Relevant differences arise in verb phrase structure, in complementation (

that

. . .,

which

. . .), and in the forms of ‘auxiliary’ operation that determine subject–verb agreement, and the like. A functional category might be expressed in different languages in different ways. In English, some prepositions (such as

of

) express a grammatical or functional difference,

others (such as

under

) a lexical content one. By assuming that some lexical items express functional categories or grammatical information alone (and not lexical ‘content’ information), and by assuming further that parametric differences between languages are different ways the language faculty has available to it to meet the “output conditions” set by the systems with which it must ‘communicate’ at its interfaces, it came to be assumed that parametric differences are lodged in “function words,” rather than in the principles themselves, as was assumed in the early account.

The other major line of development is due largely to the work of Richard Kayne (

2000

,

2005

), who pointed to many more parameters than had been thought to be required before. He called them “microparameters,” thereby turning the older parameters into “

macroparameters.” Microparameters detail relatively fine-grained differences between aspects of what are usually claimed to be closely related languages (“closely related” is not always clearly defined). The microparameter thesis came to be wedded also to the idea that all parametric differences are located ‘lexically’ (although some might be unpronounced). That idea also became a significant assumption of much work in the Minimalist Program, thereby effectively abandoning the early idea that parameters are ‘in’ principles. Discussion continues, and focuses on topics that one might expect: can macroparameters be analyzed in terms of microparameters? Is there room for an unqualified binary macroparametric distinction between languages such as that expressed in the head parameter? If so, how does one conceive it? And so on. The answer to the next-to-last question, by the way, seems at the moment to be “no,” but perhaps major features of the old conception can be

salvaged. On that, see Baker (

2008

). The discussion continues, but I do not pursue it further here. Chomsky adds something in the 2009 supplement (see pp. 54–55), however – among other things, the possibility that there are infinitely many parameters.

2000

,

2005

), who pointed to many more parameters than had been thought to be required before. He called them “microparameters,” thereby turning the older parameters into “

macroparameters.” Microparameters detail relatively fine-grained differences between aspects of what are usually claimed to be closely related languages (“closely related” is not always clearly defined). The microparameter thesis came to be wedded also to the idea that all parametric differences are located ‘lexically’ (although some might be unpronounced). That idea also became a significant assumption of much work in the Minimalist Program, thereby effectively abandoning the early idea that parameters are ‘in’ principles. Discussion continues, and focuses on topics that one might expect: can macroparameters be analyzed in terms of microparameters? Is there room for an unqualified binary macroparametric distinction between languages such as that expressed in the head parameter? If so, how does one conceive it? And so on. The answer to the next-to-last question, by the way, seems at the moment to be “no,” but perhaps major features of the old conception can be

salvaged. On that, see Baker (

2008

). The discussion continues, but I do not pursue it further here. Chomsky adds something in the 2009 supplement (see pp. 54–55), however – among other things, the possibility that there are infinitely many parameters.

Parameters continue as before to have a central role in discussions of

language acquisition or growth. Imagine a child growing up in an English-speaking environment, and take the headedness macroparameter as an example. He or she – or rather, his or her mind, for this is not a conscious decision – will set the “headedness” switch/parameter to “head initial.” The same child's mind in a Miskito-speaking environment will automatically set the parameter to “head final.” The details of how the setting take place are a matter for discovery; for interesting discussion, see Yang (

2004

) and the discussion in the main text.

language acquisition or growth. Imagine a child growing up in an English-speaking environment, and take the headedness macroparameter as an example. He or she – or rather, his or her mind, for this is not a conscious decision – will set the “headedness” switch/parameter to “head initial.” The same child's mind in a Miskito-speaking environment will automatically set the parameter to “head final.” The details of how the setting take place are a matter for discovery; for interesting discussion, see Yang (

2004

) and the discussion in the main text.

Canalization is a label for what is on the face of it a surprising phenomenon. Humans and other organisms seem to manage to develop into a relatively uniform ‘type’ despite different environments, ‘inputs,’ and genetic codings. It is not at all clear what explains the observations, although there are suggestive ideas. One is that “control” or “master” genes play a role.

Waddington, who first used the

term, spoke of epigenetic factors influencing

development. Another possible factor is the limited set of options made available, given non-genetic physiochemical, ‘processing,’ and other constraints. Since these limit possible mutation too, it would not be surprising if they limited possible organic structures and operations. Canalization is discussed further in the

text.

Waddington, who first used the

term, spoke of epigenetic factors influencing

development. Another possible factor is the limited set of options made available, given non-genetic physiochemical, ‘processing,’ and other constraints. Since these limit possible mutation too, it would not be surprising if they limited possible organic structures and operations. Canalization is discussed further in the

text.

Other books

Werewolf Me by Amarinda Jones

An Alpha's Lightning (Water Bear Shifters 2) by Sloane Meyers

Star Wars Rebels: Rise of the Rebels by Michael Kogge

Can Anyone Hear Me? by Peter Baxter

The Darkangel by Pierce, Meredith Ann

Along Came Mr. Right by Gerri Russell

The Scoundrel Takes a Bride: A Regency Rogues Novel by Stefanie Sloane

Torn Souls by Cattabriga, crystal

Baby It's Cold Outside by Kerry Barrett

The Hamiltons of Ballydown by Anne Doughty