The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (15 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

The researchers came from the Brooklyn campus of Long Island University as well as

the Mailman School of Public Health of Columbia University, a star of the biological sciences. They knew their stuff. The lead scientist, Marshall Hagins, had a doctorate in biomechanics and ergonomics and a clinical doctorate in physical therapy, and had practiced yoga for a decade.

The study’s funding signaled its gravitas. Often, yoga investigators list no source of financial backing in their published work, implying that they undertook it on their own or with the aid of anonymous colleagues. That was the case with the Davis study. Such research tends to be modest in scope because the funding tends to be modest. Not so mainstream science. There, investigators typically go out of their way to thank their patrons—in the life sciences, often federal agencies. So it was with the New York study. The team in its published report said it had received support from the National Institutes of Health, the world’s premier organization for health-care research.

The New York team recruited twenty subjects who had practiced yoga for at least one year, felt comfortable doing Sun Salutations, and could perform such advanced poses as the Headstand. The group consisted of two men and eighteen women.

The scientists judged that some of the previous studies had significant flaws. For instance, subjects were inexperienced or had been forced to wear clumsy masks and mouthpieces. “Such techniques,” the scientists noted, “may alter the performance of the yoga activities and therefore provide invalid estimates.”

Invalid estimates.

In the polite world of scientific discourse, that was tantamount to ridicule.

Seeking better results, the scientists made their measurements while the subjects did yoga in a special chamber that could track overall changes in respiratory activity. It let the yogis move about freely even while being scrutinized intimately. Known as a metabolic chamber, the rare and costly piece of scientific equipment was located at Saint Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital on the city’s Upper West Side, near the Columbia campus. It was, in effect, an airtight cell. Machines linked to the metabolic chamber could measure a subject’s exact consumption of oxygen, exhalation of carbon dioxide, and radiation of metabolic heat. Columbia scientists often used the chamber to study obesity. They would examine a subject’s metabolic rate during meals, sleep, and light activities. But now they lent their apparatus to the scrutiny of yoga. The aim was not to track the addition of layers of fat but to see

how efficiently yoga burned calories by fanning the body’s metabolic flames. In terms of sophistication and accuracy, the chamber was light-years away from the rough bags that Hill had strapped on his runners, and from the traditional sets of before-and-after measurements that some modern scientists had used to track VO

2

max. It was cutting-edge.

The architects of the New York inquiry, as with most scientists who study humans, made sure its design included the imposition of controls meant to increase the likelihood that any observed changes were real rather than false clues or statistical flukes. Thus, the subjects in the metabolic chamber engaged sequentially in three different activities—reading a book, doing yoga, and walking on a treadmill. To provide a more detailed basis for comparison, the scientists had the subjects walk on the treadmill at different speeds. The imposed rates were two miles per hour and three miles per hour, the latter a fairly vigorous pace.

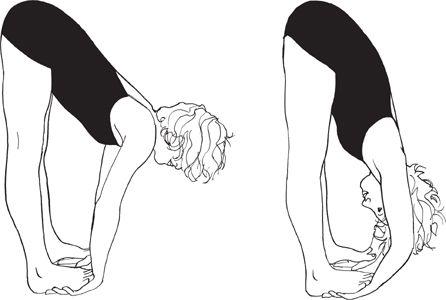

The yoga was pure Ashtanga, the brisk, fluid style descended from Krishnamacharya. The workout began with twenty-eight minutes of Sun Salutations followed by some twenty minutes of standing poses such as the Triangle and Padahastasana, a forward bend in which the student grabs the feet and brings the head down to the knees. It ended with eight minutes of relaxation in the Lotus position and the Corpse pose. Overall, the yoga session lasted nearly an hour. Its strong focus on Sun Salutations made the routine one of the most vigorous to undergo careful examination.

Hands to Feet,

Padahastasana

Despite the added zing,

the scientists concluded that the yoga session failed to meet the minimal aerobic recommendations of the world’s health bodies. Its oxygen demands, they reported, “represent low levels of physical activity” similar to walking on the treadmill at a slow pace or taking a leisurely stroll.

The only glimmer of cardiovascular hope centered, once again, on Sun Salutations. The New Yorkers found the oxygen challenge of the pose “significantly higher” than for the slow treadmill. A practice incorporating Sun Salutations for at least ten minutes, they wrote, may “improve cardio-respiratory fitness in unfit or sedentary individuals.” But the flip side, the scientists added, was that the posture offered few heart benefits for seasoned practitioners.

Seeking a wide context, the scientists were careful to note that other research had demonstrated that yoga aided the body and mind in ways that extended far beyond athletics and aerobics. Hagins, the lead researcher, remarked in a university news release that the discipline had “positive health benefits on blood pressure, osteoporosis, stress and depression.” Yoga, he added, “may convey its primary benefits in ways unrelated to metabolic expenditure and increased heart rate.”

That kind of prudence became the standard view in the world of science. Decades of uncertainty ended as a consensus emerged that yoga did much for the body and mind but little or nothing for aerobic conditioning. The California study receded as an anomaly, and the investigations in Texas, Wisconsin, and New York got cited repeatedly and respectfully in the scientific literature. Science and its social mechanisms had assessed a big claim and found it wanting.

In 2010, a review paper documented the new accord. In the halls of science, the review article is a hallowed tradition because of its pithy generalizations. It gives a critical evaluation of the published work in a particular area of research and then draws conclusions about what is legitimate progress and what is not, what is good and what is bad. By definition, it weighs

all

the evidence. Given the rapid advance of science around the globe, as well as the soaring numbers of reports, such analyses are seen as increasingly important to upholding the standard of wide comprehension. Whole journals do nothing but publish review articles.

The 2010 paper examined

more than eighty studies that compared yoga and regular exercise. The analysis, by health specialists at the University of Maryland, found that yoga equaled or surpassed exercise in such things as improving balance, reducing fatigue, decreasing anxiety, cutting stress, lifting moods, improving sleep, reducing pain, lowering cholesterol, and more generally in raising the quality of life for yogis, both socially and on the job. The benefits were similar to those that had surprised the Duke team.

In summary, the specialists reported that yoga excelled in dozens of examined areas.

But the scientists also spoke of a conspicuous limitation for an activity that had long billed itself as a path to physical superiority. The authors noted that the benefits ran through all the categories—“except those involving physical fitness.”

For the world of science, the issue seemed to be settled. But for the world at large? In truth, all the labors and analyses got little or no attention from the public, and most certainly not from yogis. The one exception was the Wisconsin study, which made a few waves. Overall, the rest of the studies sank without a ripple.

The lack of public reaction was especially notable in the yogic community. In theory, it was the main beneficiary of the findings. Even so, no yoga book to my knowledge reviewed the developments or commented on the implications. No guru expounded on the details. Bikram Choudhury offered no barbed rejoinders.

Yoga Journal

fired off no more rebuttals. The disregard persisted even though the lead researchers in the Wisconsin and New York studies were themselves yogis who could be seen as sympathetic to the discipline.

In the early days of modern yoga—in the era of Gune and Iyengar—science had been a role model. Influential gurus paid attention. No more. The affair was over.

Some individuals and authors who did yoga—or who knew the diversity of modern athletics—seemed to understand the substance of the new findings. But they tended to be exceptions. In popular culture, yoga went on its merry way, oblivious to the conclusion of science, believing deeply in its aerobic powers, often selling itself as superior to sports and exercise as the

one and only way to attain that most fashionable of goals—ultimate fitness.

Yoga Journal

continued its claims, hailing vigorous Hatha in 2008 as “a good cardio workout.”

The vibrant cover of

Yoga for Dummies

publicized its two authors as holding doctoral degrees—the ultimate academic credential. Their experience seemed to magnify their authority. The cover identified one man as the “author of more than 40 books,” and the other as an “internationally renowned Yoga teacher.” In the book’s second edition, published in early 2010, the two authorities hailed the Sun Salutation for its “aerobic benefits.” More generally, they assured readers, the newer, more vigorous formulations of the ancient discipline let practitioners “work up a sweat” to achieve “aerobic-type” workouts.

Even

The New York Times

lost its bearings. One of its companies, About.com, addressed a frequent question of readers, “Does Yoga Keep You Fit?” Yes, came the unequivocal answer. Ann Pizer, the website’s “Yoga Guide,” said recent science had revealed that students doing yoga more than twice a week “need not supplement their fitness regimes with other types of exercise in order to stay very physically fit.” She cited the original

Yoga Journal

article, the one that had turned the Davis study into a publicist’s dream come true.

An indication of the fog’s deep penetration was how it crept into the pages of

Hotel Management and Operations

—an industry guide in its fifth edition. In 2010, it advised readers that vigorous styles such as Ashtanga were ideal for getting a “cardio workout.” The language wasn’t as strong as Beth Shaw’s “tough cardiovascular workout.” But it nonetheless put the practice right up there with the sweaty rigors of fast treadmills.

The Davis and

Yoga Journal

articles kept getting cited, their claims immortalized on the Internet. The Huffington Post ran a link to

Yoga Journal

’s glowing tribute.

The aerobic mythology sped across cyberspace until it found its way to HealthCentral.com, a flourishing commercial site that sells drugs and gives away medical advice. The site claims more than seventeen million readers a month and, on its home page, proudly declares that it features material from Harvard Health Publications, the arm of the Harvard Medical School that seeks

to publicize the most authoritative health information. The site’s reference to Harvard included a picture of the school’s crest—a shield bearing three open books, their pages spelling out

veritas

—”truth” in Latin.

“Does Yoga Provide Enough of a Cardio Workout?” HealthCentral .com asked its readers in 2010.

The answer came from never-never land, despite the implication that the Harvard Medical School had somehow been involved in producing or vetting the information. It came from a place where the ancient practice had somehow morphed into a modern fitness machine.

“Rest assured,” the site told its readers. “Yoga is all you need.”

In recent years, many people have learned to ignore the exaggerated claims and the unabashed gurus (with or without fleets of Rolls-Royces). They lift weights to build muscles and run to challenge their hearts, even while pursuing yoga for flexibility and its other rewards. They are known as cross trainers. Their diverse workouts complement one another to produce a balance of benefits.

Cross training has no gurus, no schools, no fees, and no advocacy groups. Even so, it has a growing number of adherents, including top athletes. For instance, Alan Jaeger, a baseball pro with a passion for yoga, runs a school in Los Angeles for big-league pitchers. His stars run, stretch, meditate, listen to music, do yoga poses, and meditate again—doing that kind of routine for hours before getting around to throwing a ball.

The popularity of cross training serves as an instructive counterpoint to yoga’s overstated fitness claims. It speaks to the wisdom of people who pay close attention to what their bodies tell them tell them—and to the recommendations of public health officials.

The guidelines for aerobic exercise developed slowly over the course of the twentieth century, as we have seen. Ultimately, the enterprise drew on the work of hundreds of scientists. A less conspicuous effort got under way during the same period. It focused not on the straightforward goal of quantifying oxygen uptake and determining its role in physical fitness but on the more difficult and amorphous problem of understanding how changing situations can shape human emotion.