The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards (22 page)

Read The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards Online

Authors: William J Broad

Tags: #Yoga, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Science, #General

Russell’s concern went deeper. He worried about the inner brain, in particular a functionally diverse region toward the rear. His concern was that yoga postures that involved extreme bending of the neck might compromise the region’s blood supply, destroying parts of the brain rich in primal responsibilities.

The human neck is made of seven cervical vertebrae that anatomists have numbered, top to bottom, C1 through C7. Their special shapes and compliant disks make the neck the most flexible part of the spinal column. Scientists have measured the neck’s normal range of motion and found the movements to be extraordinarily wide. The neck can stretch backward 75 degrees, forward 40 degrees, and sideways 45 degrees, and can rotate on its axis about 50 degrees. Yoga practitioners typically move the vertebrae

much

farther. For instance, an intermediate student can easily turn his or her neck 90 degrees—nearly twice the normal rotation.

Russell had long specialized in understanding how the bending of the neck could endanger the flow of blood from the heart to the brain. His concern focused mainly on the vertebral arteries. By nature, every tug, pull, and twist of the head rearranges these highly elastic vessels. But major activity outside their normal range of motion can put them in jeopardy in part because of their unusual structure.

In traversing the neck, the vertebral arteries go through a bony labyrinth that is quite unlike anything else in the body and quite different from the soft, easy path that the carotids follow to the brain. The sides of each vertebra bulge outward to form loops of bone, and the arteries penetrate these loops successively in moving upward. The left and right vertebral arteries enter this gauntlet at C6 and run straight through the loops until they reach the top of the neck, at which point they start to zig and zag back and forth as they move toward the skull. Between C2 and C1, they usually bend

forward, and then, upon exiting the bony rings of C1, usually curve sharply backward toward the foramen magnum—the large hole at the base of the skull that acts as a conduit for not only blood vessels but nerves, ligaments, and the spinal cord. Anatomists describe the final journey of the vertebral arteries toward the brain as serpentine and report much variability in the exact route from person to person. It is not unusual for the tops of the vertebral arteries to branch out in a tangle of coils, kinks, and loops.

From decades of clinical practice and laboratory study, Russell knew that extreme motions of the head and neck could wound these remarkable arteries, producing clots, swelling, constriction, and havoc downstream in the brain. The victims could be quite young. His ultimate worry centered on the basilar artery. Located just inside the foramen magnum, the vessel arises from the union of the two vertebral arteries and forms a wide conduit at the base of the brain that feeds such structures as the pons (which plays a role in respiration), the cerebellum (which coordinates the muscles), the occipital lobe of the outer brain (which turns eye impulses into images), and the thalamus (which relays sensory messages to the outer brain and the hypothalamus and its vigilance area). In short, the basilar artery nourishes some of the brain’s most important areas. Russell worried that clots and cutoffs of blood in the vertebral arteries would impair the work of the basilar artery and its downstream branches deep inside the brain.

The drop in blood flow was known to produce a variety of strokes. Symptoms might include coma, eye problems, vomiting, breathing trouble, arm and leg weakness, and sudden falls—but by definition had little to do with language and conscious thinking. However, because strokes of the rear brain can severely damage the regulatory machinery that governs life basics, they can also result in collapse and death. Even so, the vast majority of patients survive the attack and go on to recover most functions. Unfortunately, in some cases, headaches can persist for years, along with such residual troubles as imbalance, dizziness, and difficulty in making fine movements.

The medical world of Russell’s day worried about these kinds of strokes, including a prominent type that began in circumstances that seemed quite innocuous. At beauty salons, during shampooing, women at times would have their necks tipped too far back over the edge of a sink, reducing the flow

of blood through the vertebral and basilar arteries. The risk was judged especially great among the elderly. With aging, the vertebral arteries can lose their elasticity and narrow, and the normally smooth neck bones can grow spurs. When the neck bends far backward, the bony spurs can compress or otherwise harm vessels already narrow and inelastic. In addition, the stagnant blood can turn into a small factory of clot production. When the neck returns to a more normal position and the flow of blood resumes, the clots can travel down the arteries, heading deeper into the brain before settling in a narrow vessel and blocking its flow. A small epidemic of strokes resulted in a diagnosis known as the beauty-parlor syndrome.

Russell warned of yoga dangers in the pages of the

British Medical Journal

, a mainstay of the field established in 1840, just as Paul was finishing medical school in Calcutta. He drew parallels between yoga and such recognized threats as the beauty-parlor syndrome, noting that some poses produce “extreme degrees of neck flexion and extension and rotation.” He specifically cited the Shoulder Stand and the Cobra, displaying a good understanding of the field. In the Cobra, or Bhujangasana, “serpent” in Sanskrit, a student lies facedown and slowly rises off the floor, pushing the trunk upward with the arms and extending the head and spine backward. Iyengar, in

Light on Yoga

, suggests that the head should arch “as far back as possible.” Photos show him doing just that, his head thrown back on a trajectory toward his buttocks—in other words, the kind of maneuver that Russell found worrisome.

Cobra,

Bhujangasana

In the Shoulder Stand,

the neck is bent in exactly the opposite direction, going far forward, with the chin deep in the chest, the trunk and head forming a right angle. “The body should be in one straight line,” Iyengar emphasized, “perpendicular to the floor.” Ever the enthusiast, he called the pose “one of the greatest boons conferred on humanity by our ancient sages.”

Where Iyengar saw benefits, Russell saw danger. The postures, he said, “must for some people be hazardous.” His choice of the word “must” betrayed the speculative nature of his worry—but one grounded in a lifetime of experience. Russell warned that the basilar artery syndrome could strike practitioners of yoga and went on to cite a shadowy complication—doctors might have a hard time discerning its origin. The cerebral damage, he wrote, “may be delayed perhaps to appear during the night following, and this delay of some hours distracts attention from the earlier precipitating factor, especially when there is a catastrophic stroke.” In that case, of course, the deceased could give no account of prior activities.

His caution went to the inherent difficulty of understanding the cause of invisible brain injuries. We typically think of illness as focused on a particular body part—such as the heart or lungs. But the origins of strokes often lie relatively far away from where they hit, starting in the wilds of the bloodstream and ending in the brain. The gap, moreover, could involve not only distance but time—hours and sometimes days—as a clot worked its way downstream or as a damaged artery slowly became swollen and gradually reduced the flow of blood. Such complicating factors meant that, for a large percentage of strokes, physicians could discover no obvious explanation. Their medical term for such injuries was

cryptogenic,

meaning their origin remained a mystery.

That kind of uncertainty had long obscured the cause and the extent of the beauty-parlor syndrome. In essence, Russell was now asking if the same thing was happening with yoga.

His alert proved timely. Perhaps he was simply ahead of his day, or perhaps his warning opened the eyes of colleagues, or perhaps the growth of yoga was resulting in more injuries. For whatever reason or reasons, an American physician in the following year, 1973, made public a gruesome case study. The author was Willibald Nagler. He worked on Manhattan’s Upper East Side at

the Weill Medical College of Cornell University. A world authority on spinal rehabilitation, he had counted President Kennedy among his patients.

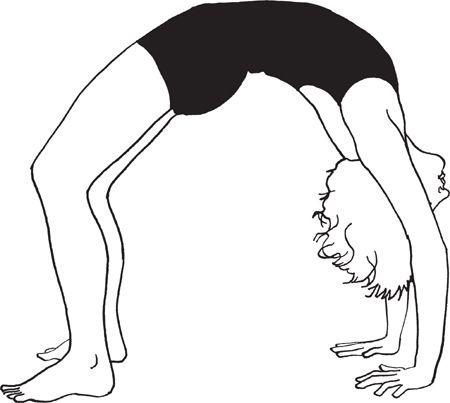

In his report, Nagler described how a woman of twenty-eight, “a Yoga enthusiast” as he called her in the sketchy anonymity of clinical reports, had suffered a stroke while doing a position known in gymnastics as the Bridge and in yoga as the Wheel or Upward Bow (in Sanskrit Urdhva Dhanurasana). The posture begins with the practitioner lying on his or her back and then pushing up, balancing on the hands and feet and lifting the body into a semicircular arc. An intermediate stage can involve raising the trunk and resting the crown of the head on the floor.

Wheel or Upward Bow,

Urdhva Dhanurasana

Nagler reported that the woman entered her crisis while balanced on her head, her neck bent far backward. While so extended, she “suddenly felt a severe throbbing headache,” he reported. She had difficulty getting up. After she was helped into a standing position, she was unable to walk without assistance.

The woman was rushed to the hospital and found to be experiencing a number of physical disorders. She could feel no sensations on the right side of her body. Her left arm and leg wavered. Her eyes kept glancing involuntarily to the left. And the left side of her face showed a contracted pupil, a drooping upper eyelid, and a rising lower lid—a cluster of symptoms known as

Horner’s syndrome. Nagler reported that the woman also had a tendency to fall to the left.

Diagnostic inquiry showed that her left vertebral artery had narrowed considerably between cervical vertebrae C1 and C2, revealing the probable site of the blockage that resulted in the stroke. It also showed that the arteries feeding her cerebellum (the structure of the rear brain that coordinates the muscles and balance) had undergone severe displacement, hinting at trouble within. Given the day’s lack of advanced imaging technologies, an exploratory operation was deemed necessary to better evaluate the woman’s injuries and prospects for recovery.

The surgeons who opened her skull found that the left hemisphere of her cerebellum had suffered a major failure of blood supply that resulted in much dead tissue. They also found the site seeped in secondary hemorrhages, or bleeding. In response, the physicians put the woman on an extensive program of rehabilitation. Two years later, she was able to walk, Nagler reported, “with broad-based gait.” But her left arm continued to wander and her left eye continued to show Horner’s syndrome.

Nagler concluded that such injuries appeared to be rare but served as a warning about the hazards of “forceful hyperextension of the neck.” He urged health professionals to show caution in recommending such difficult postures to individuals of middle age.

The next case came to light in 1977. The man of twenty-five had been in excellent health and doing yoga every morning for a year and a half. His routine included spinal twists in which he rotated his head far to the left and far to the right. Then, according to a team in Chicago at the Northwestern University Medical School, he would do a Shoulder Stand with his neck “maximally flexed against the bare floor,” echoing Iyengar’s call for perpendicularity in

Light on Yoga.

The team said the young man usually remained in the inversion for about five minutes.

One morning upon finishing this routine, he suddenly felt a sensation of pins and needles on the left side of his face. Fifteen minutes later, he felt dizzy and his vision blurred. Soon, he was unable to walk without assistance and had trouble controlling the left side of his body. The man also found it difficult to swallow. He was rushed to the hospital.

Steven H. Hanus was a medical student at Northwestern who became fascinated by the case. He took the lead and worked with the chairman of the department of

neurology to elucidate the exact cause of the disabilities, publishing a study with two colleagues when he was a resident. The doctors saw many indications of stroke and, in their report, noted the similarity of the man’s symptoms to those of Nagler’s female patient. The man could feel little sensation on the right side of his body. His eyeballs twitched. His left arm and leg were weak, had poor coordination, and showed a prominent tremor when he tried to reach for something or move his hand or foot to a precise location.