The Second Book of General Ignorance (17 page)

Read The Second Book of General Ignorance Online

Authors: John Lloyd,John Mitchinson

But Vulgar Latin was only the daily language of Latium, not the Empire. Greek was the first language of the eastern Empire, based around Constantinople and of the cities in southern Italy. The name Naples (

Neapolis

in Latin) is actually

Greek (

nea

, new, and

polis

, city). Today, the local dialect in Naples, Neopolitana, still shows traces of Greek and the Griko language is still spoken by 30,000 in southern Italy. Modern Greek and Griko are close enough for speakers to be able to understand one another. Greek, not Latin, was the popular choice for the Mediterranean marketplace.

Lingua Franca

was originally an Italian – not a Latin – term for the specific language that was used by people trading in the Mediterranean from the eleventh to the nineteenth century. Based on Italian, it combined elements of Provencal, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, French and Arabic into a flexible lingo everyone could speak and understand.

Lingua Franca

doesn’t mean ‘French language’, but ‘Language of the Franks’. It derives from the Arabic habit of referring to all Christians as ‘Franks’ (rather as we once referred to all Muslims as ‘Moors’).

Franji

remains a common Arabic word used to describe Westerners today.

There are many countries in which English is the Official Language, but England, Australia and the United States aren’t among them.

An official language is defined as a language that has been given legal status for use in a nation’s courts, parliament and administration. In England, Australia and over half the USA,English is the

unofficial

language. It is used for all state business, but no specific law has ever ratified its use.

Bilingual countries such as Canada (French and English) and Wales (Welsh and English) do have legally defined official languages. National laws often recognise significant minority

languages, as with Maori in New Zealand. Sometimes, as in Ireland, an official language is more symbolic than practical: fewer than 20 per cent of the population use Irish every day.

English is frequently chosen as an alternative ‘official’ language if a country has many native languages. A good example is Papua New Guinea where 6 million people speak 830 different languages. In the USA the campaign to make English the official language is opposed by many other ethnic groups, most notably the Hispanic community who account for more than 15 per cent of the population.

Perhaps the most interesting case of an English-speaking country that doesn’t have English as its official language is Australia. As well as large numbers of Greek, Italian and South-East Asian immigrants, Australia is home to 65,000 native Maltese speakers. There are also 150 aboriginal languages which are still spoken (compared to the 600 or so spoken in the eighteenth century). Of these, all but twenty are likely to disappear in the next fifty years. Attempting to declare English the official language risks looking insensitive.

The Vatican is the only country in the world that has Latin as an official language.

6 April 2010.

With a few minor exceptions, slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1833, but it wasn’t thought necessary to outlaw it at home.

In 1067, according to the Domesday Book, more than 10 per cent of the population of England were slaves. The

Normans, perhaps surprisingly, were opposed to slavery on religious grounds and within fifty years it had virtually disappeared. Even serfdom (a kind of modified slavery) became increasingly rare and Queen Elizabeth I freed the last remaining serfs in 1574.

At the same time, Britain was becoming a colonial power and it was the height of fashion for returning Englishmen to have a ‘black manservant’ (who was in fact, of course, a slave). This unseemly habit was made illegal by the courts in 1772 when the judge, Lord Mansfield, reportedly declared: ‘The air of England is too pure for any slave to breathe’, with the result that thousands of slaves in England gained their freedom.

From that moment, slavery was arguably illegal in England (though not in the British Empire) under Common Law, but this was not confirmed by Parliament until the Coroners and Justice Act.

Previous acts of Parliament dealt with kidnap, false imprisonment, trafficking for sexual exploitation and forced labour, but never specifically covered slavery. Now, Section 71 of the Coroners and Justice Act (which came into force on 6 April 2010) makes it an offence in the UK, punishable by up to fourteen years’ imprisonment, to hold a person in ‘slavery or servitude’.

‘Servitude’ is another word for serfdom. A serf is permanently attached to a piece of land and forced to live and work there, whereas a slave can be bought and sold directly like a piece of property. It’s a fine difference: in fact, the English word ‘serf’ comes from the Latin word

servus

, ‘a slave’.

Until now, the lack of a specific English law has made it hard to prosecute modern slave-masters. There’s a difference between ‘abolishing’ something and making it a criminal offence. Although slavery was

abolished

all over the world many

years ago, in many countries the

reality

only changed when laws were introduced to punish slave owners.

You might think slavery is a thing of the past and isn’t relevant to modern Britain, but there are more slaves in the world now – 27 million of them – than were ever seized from Africa in the 400 years of the transatlantic slave trade. And forced labour, using migrant workers effectively as slaves (and also outlawed by the Act), is widespread in Britain today.

Under the Criminal Law Act 1967, a number of obsolete crimes were abolished in England including scolding, eavesdropping, being a common nightwalker and challenging someone to a fight.

It is odd to think that, in the year England won the World Cup, eavesdropping was still illegal but slavery wasn’t.

ALAN

I bet it was one of these odd little New Labour laws in about

1996,

7, 8 …STEPHEN

What an odd law, to outlaw slavery. It’s political

correctness gone mad!

It does have one.

The idea that Britain has an ‘unwritten constitution’ has been described by Professor Vernon Bogdanor, the country’s leading constitutional expert, as ‘misleading’.

The rules setting out the balance of power between the governors and the governed

are

written down. They’re just not all written down in

one place

.

The British constitution is composed of several documents,including Magna Carta (1215), the Petition of Right Act (1628), the Bill of Rights (1689), the Act of Settlement (1701), the Parliament Acts (1911 and 1949) and the Representation of the People Act (1969). Between them, they cover most of the key principles that, in other countries,appear in a single formal statement: that justice may not be denied or delayed; that no tax can be raised without parliament’s approval; that no one can be imprisoned without lawful cause; that judges are independent of the government; and that the unelected Lords cannot indefinitely block Acts passed by the elected Commons. They also say who can vote, and how the royal succession works.

There’s also ‘case law’, in which decisions made by courts become part of the constitution. An important example is the Case of Proclamations (1611), which found that the king (and thus his modern equivalent, the government) cannot create a new offence by merely

announcing

it. In other words,nothing is against the law until proper legislation says it is.

The reason why Britain doesn’t have a single written document (and almost every other parliamentary democracy does) is to do with its age. The British state has evolved over a millennium and a half. It had no founding fathers, or moment of creation, so its constitution has continued to develop bit by bit.

This has left some surprising gaps. The Cabinet has no legal existence; it is purely a matter of convention. The law established neither of the Houses of Parliament and, although the office of Prime Minister was formally recognised in 1937,British law has never defined what the PM’s role actually is.

But that’s not as unusual as it might sound. There is no constitution anywhere whose authors have thought of everything. The US Constitution does not contain one word on the subject of how elections should be conducted.

Whether that would surprise many US citizens is hard to say. In 2002 a survey by Columbia Law School found that almost two-thirds of Americans identified the phrase ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’ as a quotation from the US constitution rather than coming from the pen of the founder of communism, Karl Marx (1818–83).

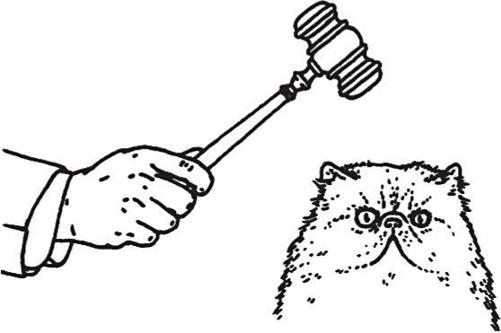

British judges do not, and never have, used gavels – only British auctioneers.

Actors playing judges on TV and in films in Britain use them because their reallife American counterparts do. After decades of exposure to US movies and TV series, they have become part of the visual grammar of the courtroom. Another self-perpetuating legal cliché is referring to the judge as ‘M’Lud’. Real British barristers never do this: the correct form of address is ‘My Lord’.

The origin of the word

gavel

is obscure. The original English word

gafol

dates from the eighth century and meant a ‘payment’ or ‘tribute’, usually a quantity of corn or a division of land. The earliest known use of the word

gavel

to mean ‘a chairman’s hammer’ dates from 1860, so it’s hard to see a connection. Some sources claim it might have been used earlier than this among Freemasons (as a term for a mason’s hammer), but the evidence is faint.

Modern gavels are small ceremonial mallets commonly made of hardwood, sometimes with a handle. They are used to call for attention, to indicate the opening (call to order) and closing (adjournment) of proceedings, and to announce the striking of a binding bargain in an auction.

The US procedural guidebook –

Robert’s Rules of Order Newly

Revised

(1876) – provides advice on the proper use of the gavel in the USA. It states that the person in the chair is never to use the gavel in an attempt to drown out a disorderly member, nor should they lean on the gavel, juggle or toy with it, or use it to challenge or threaten, or to emphasise remarks.

The handleless ivory gavel of the United States Senate was presented by the Republic of India to replace one that had been in continuous use since 1789. The new one was first used on 17 November 1954. The original had been broken earlier in 1954, when Vice-President Richard Nixon brandished it during a heated debate on nuclear energy. Unable to obtain a piece of ivory large enough to replace the historic heirloom, the Senate appealed for help to the Indian embassy, who duly obliged.

The gavel of the United States House of Representatives is plain and wooden and has been broken and replaced many times.

STEPHEN

British judges have never had gavels. Never.JACK DEE

Sometimes, if they’re conducting an auction at the same

time, they do.

If you read the British popular press, your answer is bound to be: ‘wear hairnets’. This isn’t true.