Authors: Jack Weatherford

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the Daughters of Genghis Khan Rescued His Empire (29 page)

“It would be much better for all of us,” the first person answered, presenting a simple and practical reason that the nation needed a fully grown man. It will be better for the nation “if you would accept the proposal of Une-Bolod.”

The second speaker disagreed, with a longer and more profound explanation. For Manduhai to marry outside the lineage of Genghis Khan, even if it were to a descendant of his brother, “your path will grow dark.” With such a marriage, she would no longer be the queen. “You will divide yourself from the people, and you will lose your honored and respected title of

khatun

.” If Manduhai would devote her life to the Mongol people without thinking of personal comfort or benefit, she was told, she would follow the white road of enlightenment for herself and her nation.

Manduhai thought about the responses for a moment, and then she turned to the one who recommended that she accept Une-Bolod’s

proposal. “You disagree with me just because Une-Bolod is a man and I am only a widow,” she charged. Growing angrier as she spoke, she said, “Just because” I am only a woman, “you really think that you have the right to speak to me this way.”

Queen Manduhai raised a bowl of hot tea and flung it at the head of the supporter of this marriage. Manduhai had made the first independent decision of her life. She had decided not to marry any of her suitors. She was the Mongol queen, and she would make her own path.

It was the Year of the Tiger.

1470–1509

Queen Manduhai the Wise, recalling the vengeance of

the former khans

,

set out on campaign

.

She set in motion her foot soldiers and oxen-troops, and

after three days and nights she set out with her cavalry

.

Queen Manduhai the Wise, putting on her quiver

elegantly

,and composing her disordered hair

,

put Dayan Khan in a box and set out

.A

LTAN

T

OBCI

§ 101

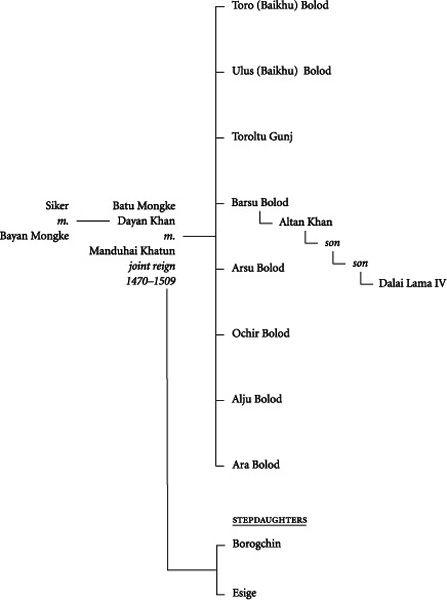

Family of Manduhai Khatun and Batu Mongke Dayan Khan

The White Road of the Warrior Widow

The White Road of the Warrior WidowM

ANDUHAI WISHED TO RULE, BUT NOT ONLY DID SHE

have no experience, she had no army. All the soldiers were loyal either to their respected general Une-Bolod or to Ismayil Taishi, the highest ranking official in the government.

Yet Manduhai had one thing they did not have—a baby boy. This was not her own child; he was the abandoned infant of the Golden Prince. He was the only living male descendant of the bone of Genghis Khan, the son of the

jinong

and the heir of the Great Khan.

The boy’s name was Batu Mongke, son of Bayan Mongke and Siker. The child was born in the South Gobi—one of the most sparsely settled areas of the Mongols’, with broad expanses of rocky steppe essentially void of vegetation except sparse clusters of grass. The harsh area, however, was not hostile to herding. With easy movement, the herders could take their animals from a place with no grass into one where the rain fell.

A thin ribbon of mountains, known as the Three Beauties (Gurvan Saikhan Nuruu), slices through this part of the Gobi. The mountains form the tail end and the most southeastern extension of the larger Altai range. Here they gradually disappear into the gravel and sand of the Gobi. On an otherwise flat terrain, their relatively modest-sized peaks seem lofty and dramatic; they climb high enough to snag some of the moisture passing overhead in the winter. These snows melt in

the summer and run into ravines and small brooks that make this area an ideal place for herding animals. Mountain springs provide water during the summer, and the canyon walls block the Arctic winds in winter. The ravines and canyons form a labyrinth that offers quick protection to the local residents from intruders or passing armies. A network of goat tracks across the mountains connects the larger canyons with one another.

Although sparsely inhabited, trade routes crisscross the area, keeping it from being truly isolated. The vast open area of the Gobi connects the northern part of the fertile Mongolian steppe with the southern part of the plateau in China’s Inner Mongolia. Similarly, the mountains moving toward the northwest connect the area into the more fertile expanses of western Mongolia.

With his father murdered and his mother kidnapped, Batu Mongke passed from hand to hand. His mother, Siker, now the wife of Ismayil, in time had children and created a new family with her husband, seemingly without regret for the husband or the child she had lost.

At first, Batu Mongke apparently lived alone with an otherwise unknown old woman referred to as Bachai of the Balaktschin. In her extreme poverty, she seemed barely able to survive by herself and proved either unable or unwilling to care for the infant. In an exceptionally harsh and sparsely populated environment such as the Gobi, a child is more dependent on its mother or other caretakers than children growing up in a benign climate surrounded by people.

The temperature drops so low at night that, even under blankets, children cannot generate enough warmth to survive. They must sleep next to larger adults or at least clumped together with several other children. During the day, the child must be carefully monitored with frequent rubbing of the hands, feet, and exposed parts of the body to prevent frostbite. In a milder climate, a urine-soaked child might develop painful skin irritations with the potential for longer-term problems, but in the Gobi, the urine can quickly freeze and threaten

the life of the child immediately. Even a simple fall outside can quickly lead to death if the child is too slow to get up again. In the fall and spring dust storms, a child can become lost within only a few feet of the

ger

and gradually be buried and suffocated in the dust.

Children typically nurse for several years, and supplement this with the rich dairy products available in the fall, but when winter sets in, the child must eat meat or very hard forms of dried and cured dairy products. To survive on the meat and harsh foods of the Gobi, the child must have the food partially chewed by an adult or much larger child in order to swallow and digest it.

Bachai did not provide the intensive care the boy needed, and after three years of neglect, Batu Mongke was still alive, but just barely. As one chronicle states, he was “suffering from a sickness of the stomach.” Another reported that he acquired “hunchback-like growth.” Manduhai learned of the child’s existence and his perilous situation, and she arranged for allies to rescue him and place him with another family. Had the existence or location of the only male descendant of Genghis Khan become generally known, it was nearly certain that one faction or another would have tried to kidnap him or kill him in pursuit of some nefarious plan.

A woman named Saichai and her husband, Temur Khadag, who is sometimes credited along with his six brothers with being the child’s rescuer, became the new foster parents for the boy, and set about trying to restore his health and rehabilitate his body. His new mother instituted a long treatment in the traditional Mongolian art of therapeutic massage or bone setting known as

bariach

. Gentle massage and light bone adjustment still forms a regular part of child rearing among the Mongols and is viewed as essential to the child’s body growing in a properly erect and aesthetically pleasing manner. Older people in particular, such as grandparents, sit around the

ger

in the idle hours, rubbing the child’s muscles and tugging at the bones and joints.

Saichai rubbed the child’s wounds with the milk of a camel that had recently given birth for the first time. The milk was prepared in a

shallow wooden bowl with a veneer of silver over the wood. Both the milk and the silver had medicinal properties important to Mongol medicine. The treatment required persistent massage by rubbing the milk onto the damaged parts of the boy’s body and rubbing the warm silver bowl itself against the afflicted area. By this persistent massage of his damaged, but still growing, body, the bone setter gradually adjusted the boy’s bones and gently pushed them back into proper alignment. In the words of one chronicle, she wore through three silver bowls trying to repair Batu Mongke’s broken body. As is so often the case with suffering, the physical damages proved easier to treat than the emotional ones.

After the good care of the foster family, Manduhai sent for Batu Mongke when he was about five years old. His foster father set out with him on a horse to escort him across the Gobi to the royal court, but while crossing a stream, the boy fell from the horse and nearly drowned before the father could jump from his horse and rescue him. Since the streams of the Gobi are quite small and only rarely have water in them, it seems strange that the boy would have had so much difficulty getting up and remounting his horse unless he was already badly injured or was severely hurt in the fall. For whichever reason, he arrived at the camp of Manduhai in quite bad physical condition, and his survival remained in doubt for some time.