The Setting Sun (11 page)

Authors: Bart Moore-Gilbert

I’m more relieved than anything. All I can think of is getting my aching bones to bed. I reassure him I’ll have no problem passing the time at the SIB.

When I report to the old Special Branch building the following morning, Poel’s not there. He’s apparently been called away to a meeting of police chiefs in Nagpur. Afterwards, he’s going on Christmas leave. To my immense relief, however, he’s left instructions for me to be admitted to Records. The chief archivist, Mr Walawalkar, is charming, middle-aged, very dark, breath smelling of fried chicken. However, he doesn’t seem to recognise Shinde’s file numbers or know where the confidential weekly reports might be located. I’m taken aback.

‘Records system changed in late 1980s,’ he explains apologetically. ‘Reorganisation. Some older material moved to different parts of the building.’

Walawalkar takes my list and promises to begin searching. Meanwhile, he suggests that the ‘Indian National Congress’ holdings might provide an overview of the contexts out of which the Parallel Government mobilisation emerged. It may even contain some of the material I’m after. He parks me at a desk in an annexe to the large room he works in. It has its own side door onto the outside corridor, past which uniformed personnel scurry. As I finish the cup of tea Mr Walawalkar offers, an attendant arrives, struggling with armfuls of dark-blue folders from the 1940s.

They have a strange odour, both acid and musty. Even more curious is the miscellany of documents they contain: crude cyclostyled anti-British cartoons, intercepted letters, Government Orders, abstracts of secret intelligence, telegrams between ‘Crimbo’ and ‘Peeler’. CID and the ordinary police, presumably? I begin working my way through, page by disintegrating page, trying not to damage them further. Within an hour, I strike gold. Here’s a document signed by Bill, reporting on two nationalists he’s taken in for questioning in Nasik. It gives his rank as assistant district superintendent of police, and is dated 7 August 1943. There are no details about the outcome of the investigations. Similar documents follow at intervals, his signature unformed compared with the one I remember.

Slowly, out of the seemingly random mass of material, I start to build a profile of Bill’s activities in the period before he went to Satara. He certainly had his hands full. On one occasion, he raids a photography shop suspected of supplying chemicals to nationalists to make crude explosives. Another time, he reports defusing a Mills bomb rigged up to a railway bridge. I remember the scars on Bill’s legs, and begin to understand how easy it might have been to come by them in the course of dealing with an armed insurgency. It must have taken some nerve to approach this sort of device and neutralise it, doubtless without proper tools or today’s protective

clothing. Less dramatically, he visits schools to warn against the blandishments of ‘extremists’. He investigates anonymous tip-offs about the political sympathies of government employees, most of which, to his evident satisfaction, turn out to be malicious. He seeks to discover who pasted up nationalist flyers and where they were printed. He searches bookshops for proscribed publications, and enforces cinema censorship regulations relating to the reporting of the war. He even visits US army units in nearby Deolali Camp, to ask them not to send home photos of the base in case they fall into the wrong hands.

The evidence suggests that Bill was very much a cog in the imperial machine during a particularly repressive phase of its history, as the British struggled to contain the twin threats represented by the Japanese land advance towards India and the surging tide of Indian disaffection. Several things in the folders strike me about the nature of the nationalist agitation. The first is how controversial violence was considered to be, as a mode of resistance to the Raj. I come across the very last message from the Indian National Congress executive before it was arrested and detained en masse in August 1942. The directions are unambiguous: ‘Every man is at liberty to do by non-violent way, any act that will disturb the Government work completely. Make it impossible for the British to rule by observing general strikes and by any other non-violent means possible … Do or die.’ It’s signed by Gandhi, the ink surprisingly fresh-looking. Congress sympathisers reiterate the thrust of these instructions, even as armed resistance begins to spread. One activist’s letter, intercepted at the height of the disturbances in 1944, insists that ‘it cannot be said that such acts of violence and sabotage … have the sanction either of Gandhi or the Congress … People should non-violently agitate against repression.’ If what Rajeev hinted about the methods used by the Parallel Government is true, it’s little surprise that the Mahatma denounced the movement as a betrayal of his

principles. From what I had time to read, this is an issue which Shinde seems to have skated over.

The Parallel Government aside, not everyone toed the official Congress line. Letters intercepted by Special Branch often equate Britain with Hitler’s Germany and call for armed rebellion, even total war, against foreign rule. There are frequent reports of sabotage; and evidence of occasional direct attacks on British personnel, notably a bomb planted in a Poona cinema which killed a number of soldiers. As one might perhaps expect, the authorities describe as ‘terrorists’ all those seeking to resist their rule by such means. Perhaps more surprisingly to a modern eye, the term ‘terrorist’ is sometimes used as a badge of honour by nationalists themselves. Here’s a cyclostyle of May 1943 lamenting the death in a police raid of one Comrade Kotwal, described as ‘this brilliant terrorist … the immortal martyr of Maharashtra’.

Above all I’m struck by how vulnerable the Raj seemed to its supporters, especially after the fall of supposedly impregnable ‘Fortress Singapore’ to the Japanese in late 1941. There’s a recurrent note of panic in many of the letters opened by the censors after that event. A Hungarian Jew, recently escaped from Europe, complains that he’s escaped the frying pan only to fall into the fire of civil disorder in Bombay. In September 1942, a Russian in Goa writes to his brother: ‘One cannot help thinking that the world will be organized by Hitler … if he succeeds in breaking through in the Caucasus, in 2–3 months he will reach India and join the Japanese.’ Foreign nationals, British citizens and Indians alike, evidently believed at various times that the Japanese had already entered India through Assam, even that Bombay had been bombarded from the sea. Air-raid precautions were hastily improvised, and lines of retreat to the hill stations planned in detail. The government was sufficiently concerned about the Province’s porous coastline to set up watchtowers along the entire littoral, from Goa to Sindh, and introduced a system of licences for fishing-craft.

A bass note sounds through the authorities’ response to such developments – fear of a repeat of the great Indian ‘Mutiny’ of 1857, which for a time threatened to bring British rule to an end. In one report, they are exercised to catch the author of a message to an Indian soldier overseas, which confidently predicts that ‘on the 13 June, 1943, all of the Collectors [chief district administrators], wherever they are in India, will be killed.’ In Satara, the situation was growing grave. A magistrate writes in September 1942 that ‘the lives of the Government officials and property are in imminent danger … and public safety is in general danger.’ Things must have got much worse by the time Bill was posted there, more than a year later. I wonder if he was prey to such anxieties, and whether they influenced the way that Shinde alleges he behaved in villages like Chafal.

By the end of my first day’s digging, I’ve amassed three pages of useful notes, but found nothing on Bill’s actual dealings with the Parallel Government. Indeed there’s been surprisingly little reference altogether to the movement. And although I’ve come across excerpts from some police officers’ confidential weekly reports, there’s no sign of my father’s, even from the period when he officiated as DSP in Nasik, during his superior’s absence on leave. Thinking about it overnight, I decide to change tack. The following morning I consult Walawalkar, who now belatedly explains how the British organised their records. I ask to see the list. The headings include ‘Foreigners’, ‘Communal Troubles’, ‘Special Crimes’, ‘Native States’ and – the word leaps out – ‘Terrorism’. I suddenly intuit why the Parallel Government is barely mentioned in the Congress files. The Raj doubtless drew a distinction between ‘legitimate’ political opposition and organisations like the PG – or the Hoors of Sindh.

I ask for everything under ‘Terrorism’, starting in 1941, the year Bill graduated from the Police Training School, up

to 1945, when he left Satara. Walawalkar looks uncertain. He says they may take time to locate, because they were moved to a different part of the building during the ‘reorganisation’ he mentioned yesterday. In the meantime, he wonders, would I like to look at anything else? Remembering Lindsay Padden-Row’s correspondence about the internment camp at Satara, I decide to examine ‘Foreigners’, the files for which arrive quickly. They seem primarily concerned with spies and fifth columnists. To my surprise, however, they yield useful material, with reports both made to and by Bill. I also sometimes catch a heartening glimpse of his personality through the official-speak.

Here’s one example; ironically, it concerns Bill being hauled before his own superior in Nasik. He’s been at a dinner attended by a Frenchwoman, identified only as Madame Agnes; she describes the occasion in a letter, pounced on by the censors. According to her account, at one point during the evening she complains to Bill that the bread tastes dreadful. He takes a bite, makes a face and advises her against eating any more. When asked why, he says it’s probably poisoned. While I can immediately visualise the puckish mock-solemn expression which so often accompanied his jokes, Madame Agnes takes him seriously: ‘He is the Asst Supt of Police, so he should know … funny thing, though, I’ve had tummy trouble for four days.’ The censors demand that both Bill and Mme Agnes be formally reprimanded by the DSP for spreading demoralising rumours, prejudicial to the war effort. According to his superior’s minutes, Bill insists it was, indeed, simply a joke – after all, he’d swallowed his mouthful in front of her. The DSP decides to give the Frenchwoman a mild warning and a brief introduction to the vagaries of English humour.

A second nugget which brings Bill vividly to life comes in another intercepted letter: ‘The turkeys travelled down very well with the exception of one hen bird which had a swollen and lame right leg … the ducks seemed in perfect condition except one which had a very husky throat and is also being treated.’ Again, I can easily visualise Bill’s struggle to keep a straight face as he comments: ‘Although I am no ornithologist, mention of a duck suffering from a husky throat sounds somewhat peculiar and indicates the use of some sort of code in the letter.’ He decides to investigate the writer, though the outcome isn’t recorded anywhere that I can see.

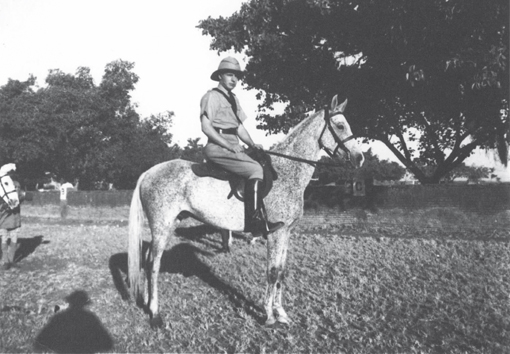

Bill on horseback

When I’ve finished flicking through ‘Foreigners’, I return to Walawalkar’s desk. ‘Very useful, thank you. Any news about the “Terrorism” holdings?’