The Shadow Dragons (14 page)

Read The Shadow Dragons Online

Authors: James A. Owen

He finally gripped the railing to steady himself, then repeated the words he’d spoken: “The place you’re seeking isn’t there.”

Edgar Allan Poe quietly descended the staircase and moved around the table to take his place at the head—a place John had assumed was reserved for Jules Verne.

“Is Poe the Prime Caretaker?” he whispered.

“You’ve already guessed that Verne has that title,” Bert whispered back, “but we can discuss that another time. Poe is something else altogether. He may have a mild manner and bearing, but believe you me—he functions on an entirely different level from the rest of us.”

The regard the Caretakers Emeritis held for Poe was evident in their treatment of him. Not a one among them stirred or spoke. The slight man sat and moved some stray strands of hair out of his eyes; then he leaned back, clasping his hands together.

“One of the reasons I shared my discovery of the Soft Places,” he began, “is because they are not just places of sanctuary, but may also be used as beachheads against us in the war. We have sent our agents out among the myriad dimensions not only to act as our messengers, but to serve as our spies. The enemy’s refuge must be somewhere.”

“But most of the Crossroads end at taverns or inns,” said Jamie. “Even accounting for a portion of the lands around them, they just aren’t large enough. It would have to be a hidden village, like Brigadoon.”

“Brigadoon is simply a story from the Encyclopedia Mythica,” Poe said, “but in principle, you are correct. There must be a township, or a village, or an island somewhere among the Soft Places large enough to contain the armies of the Winter King and his allies. If we are to gain an advantage, we must find that place.”

“Whom do we have out?” Chaucer asked.

“Hank Morgan, Alvin Ransom, and the Rappaccini girl,” said Twain. “And Dr. Raven. You know what happened to Arthur Pym.”

“Yes,” said Poe. “Most unfortunate.”

“They should be reporting in soon,” said Twain. “I’ve sent them messages via the Trumps, and their information may prove very useful, especially now that all the major players are here.”

“I agree,” said Poe. “We shall adjourn for the evening, to rest and recharge, so that we are prepared for what is to come.”

The Caretakers all stood up from the table with Poe and moved to various parts of the house to commiserate in small groups. Quixote sat with Spenser, Cervantes, and Brahe by the great fireplace, and in one of the anterooms, Defoe and Swift were showing Rose how to make treasure maps. “You see,” Defoe explained as he drew on a sheet of parchment, “you make any shape that seems right. Then you use the names of anyone around you to name the geographical details, like marshes, and rivers, and mountains. And then you make an

X

where you want the treasure to be. And I promise you, if you find an island that matches the map, you’ll also find the treasure.”

“Or you’ll be shot by tiny people with tiny arrows,” said Swift. “And you don’t want to know about the talking horses.”

“I swear, I thought they were centaurs,” protested Defoe.

“Daniel, Jonathan,” Twain said in warning. “Watch your tongues when there’s a lady present.”

“Sorry,” Defoe and Swift said together.

Professor Sigurdsson was fascinated by Archimedes and retreated with the owl to the library for a game of chess before John could pull him aside.

He had wanted to speak to the professor at length, but Bert tugged on his arm before he could follow them. “There’ll be plenty of time to speak to Stellan later,” Bert said. “The master of the house would like a private audience with the three of you upstairs in his quarters.”

“Poe wants to talk to us?” Charles exclaimed. “Wonderful!”

“Just be careful,” Bert cautioned as they ascended the stairs. “He is most trusted, but he is very eccentric. He doesn’t always make sense—not at first, anyway. But he is always worth listening to, and he is responsible for everything we have. Even Jules defers to him.”

“Lead on, MacDuff,” said Jack.

“That bird is a bad influence,” Bert said. “On

all

of you.”

Four flights up, Poe’s own space in Tamerlane House was a room barely sixty feet square. In one corner was a shabby little camp bed, under which a pair of shoes were neatly placed. In the opposite corner were a writing desk and a simple tallow candle. There was no other furniture, or indeed, decoration of any kind in the room. It was the one place in that entire exceptionally colorful house that seemed to have had the color leached from it. John thought it was the most melancholy room he’d ever seen.

Poe was sitting at the desk, writing.

“What do you think of utopias?” he asked without turning around.

“I’m for them, myself,” said Charles.

“It would depend,” said Jack. “I worry that we’d grow stagnant as a civilization if we truly lived in a utopia.”

“Your mentor, Master Wells, had the same worry,” said Poe. He turned around and looked at John, his eyes huge in the dim light of the candle. “Do you know what kind of problem I have with utopias?”

John blinked. “I’m sure I have no idea,” he said.

“Pistachio nuts,” Poe said. “None of them mention pistachio nuts. I love them myself—but they seem to get left out of all of the perfect societies. Would you like a pistachio nut?”

Without waiting for an answer, he held out his hand and dropped a nut into each of the companions’ hands. He popped one into his mouth and crunched on it, so the others did the same.

“Follow me,” Poe said, rising from the chair, still chewing. “I’d like to show you something.”

He led John, Jack, Charles, and Bert down a long hallway that became taller and narrower as they went. Near the end, they found they had to turn sideways just to squeeze through.

“You all right, Jack?” asked John.

“Yes,” Jack grunted. “Just regretting eating so many of Mrs. Moore’s meat pies.”

At the end of the hall was a wide atelier lit by a massive chandelier, and at the far side of the room, near a window, sat a man, painting.

“Basil Hallward, our resident artist,” Poe said in introduction. “Oscar Wilde discovered the young man at Magdalen and found he had a remarkable gift for portraiture. We brought him here and commissioned him to create the portraits of past Caretakers.”

Hallward glanced over at the companions and nodded distractedly, then did an abrupt double take. He jumped to his feet and threw a sheet over the canvas in progress.

“I say,” Charles remarked, “were you by chance painting a portrait of me?”

Hallward choked, then looked to Poe, who calmly returned the artist’s gaze before looking up at Charles.

“Ransom,” Poe said simply. “He was painting Alvin Ransom.”

“You do look quite similar, Charles,” said Jack.

“My word,” Charles exclaimed. “I hope nothing’s happened to the poor fellow.”

“Oh, no, not at all,” Poe answered. “It’s just a precaution. What’s useful for us Caretakers is also useful for our apprentices.”

Hallward nodded. “Useful, yeah. Useful.”

“I agree,” a voice said behind them. It was Defoe. “Nothing like having someone handy who can—literally—paint the illusion of life,” he said cheerfully.

Poe looked askance at Hallward. “You’ve painted pictures for some of the others?”

“I’ve considered availing myself of his services once or twice,” Defoe said, smirking.

“Now, Daniel,” said Bert, wagging a finger in warning, “we’ve cautioned you about that before. Caretakers only. It’s too dangerous to have others hanging around the gallery who might overhear our secrets without the oath of secrecy to bind them.

“And you,” he finished, pointing at Hallward. “No freelancing.”

“Yes, sir,” the painter said, chagrined.

“Caretakers only?” Jack whispered to Charles. “But didn’t he just say that Hallward was completing a painting of Ransom?”

“Poe said apprentices, too,” Charles reminded him.

“May I have a word?” Defoe said to Poe. “I’d like to discuss the Kipling situation.”

“Don’t worry,” said Bert. “I’ll see the lads to their rooms.”

He led the companions back out of the atelier and closed the door. “Defoe and Kipling were close,” he explained. “This has got to be quite a blow for him.”

“For us all,” said Jack. “I just wish we’d said something earlier.”

“Not everything can be forecast,” said Bert. “Not even the things we already know will happen.”

“Isn’t it risky that so many future events are known and being acted on?” asked Jack. “Won’t that disrupt the future—or worse, corrupt the prophecies?”

“Jules and I decided some time ago to view everything as being the past,” said Bert. “That’s one advantage of having lived eight hundred thousand years in the future. If I view it all as history, then all we’re doing is trying to shape the best history possible. Sometimes that means keeping information, such as the prophecies, a secret. And other times it means sharing as much information as possible about the immediate future so that the right preparations can be made.”

“Or so that you can pinch books of American presidential quotations from thirty years hence, so you can sound erudite and wise,” John said, winking.

“Will you let that go?” said Bert irritably. “I tell you, if Milton had heard Kennedy speak, he’d have swiped it himself.”

“What do you mean by ‘immediate future’?” asked Charles.

“No more than a century or two,” said Bert, “but that’s one of the reasons we do use the knowledge. My own chronicle warned of that.”

“The Shape of Things to Come”

said John. “I read it, but it came out in the thirties and was written by

our

Wells, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” said Bert. “It was based on my own version, but with two major differences. While both predicted World War II, and both saw it as lasting for two decades and ending with a plague that nearly destroys the world, his ends with an eventual utopian society, and mine does not.”

“What’s the other difference?”

“His was fiction,” said Bert, “and mine is not; it is occurring as we speak.”

“So the Winter King is trying to create the Winterland,” said Jack.

“That’s why we hoped to start our countermeasures in 1943,” said Bert. “I fear he already

has

.”

The Adversary

The night passed quickly

, and when the Caretakers all gathered again in the conservatory for breakfast, the sun was still low on the horizon.

“The Caretakers keep Oxford hours, it seems,” Jack said, yawning. “Early to bed, early to rise. I can’t believe we’re the last ones awake.”

“I don’t think they have to sleep when they’re in the paintings,” said Charles. “Or if they do, it’s not because of exhaustion.”

“Maybe we’ll be paintings here someday,” said John. “Won’t that be a nice thing to look forward to in our old age? The chance to do it all again?”

Jack started to respond, but Charles scowled and walked away, waving a hand in greeting at some of the other Caretakers.

“What’s gotten under his hat?” said John.

“I think he’s just worried,” Jack replied. “There’s a lot to process, even for someone of Charles’s perception.”

The Feast Beasts had once again served an extraordinary repast. Fresh fruit, of varieties both identified and not; vegetables of unusual shapes and colors, which nevertheless exuded fantastically saliva-inducing aromas; eggs Benedict; milk from eight kinds of cows, three kinds of goats, and one more animal—the pitcher of which no one would touch. There were green eggs and ham, hashed brown potatoes, and country-style omelets.

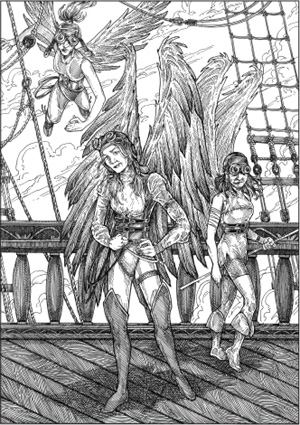

Three . . . glided close, then landed smoothly on the

deck.

“I’m normally as carnivorous as the next man,” Jack said to Bert, “but we have lots of friends here in the Archipelago who are talking animals, and there are at least three dishes on the table featuring ham. It’s making me a little uncomfortable.”

“Worry not,” Bert said as he sat at the table and tucked a napkin into his collar. “For one thing, there are certain dishes, such as my beloved eggs Benedict, that just aren’t the same without meat. And for another thing, it’s no one you know.”

“Very comforting,” said Jack.

The Caretakers were just finishing up the breakfast feast when Charles, Jack, and John pulled Bert into the corridor for a word in private.

“I hesitate to bring this up too loudly,” Charles said, looking around almost guiltily, “but you’ll understand, considering the reaction everyone had when Kipling couldn’t produce a pocket watch.”

Bert grinned. “You’re worried because you and Jack don’t have watches.”

“Precisely.”

“Understandable, my boy, totally understandable,” said Bert. “But you needn’t have worried. For one thing, you are current Caretakers. If we didn’t trust you, you would not have kept the job this long, especially given some of the, ah, hiccups of your tenure.

“For another, we believe you three to be the scholars mentioned in the Prophecy. No amount of precaution would prepare us if you chose to cross over to the other side.

“And lastly, it wasn’t until after 1936 that we realized we had to discover some way to identify our own agents—and we’d already used the watches to do so in a limited capacity. So in short, the reason you don’t have watches yet is because you disappeared for seven years, and we hadn’t had the chance to give them to you yet.”

“Whew,” said Charles. “I’m very relieved.”

“So am I,” said Jack. “Everyone here seems fairly civilized, but for an instant I flashed on the distressing notion that I might have to go toe to toe with Hawthorne.”

Bert led the three companions up a winding flight of stairs to a hallway that was so cramped and tiny that they had to crouch to make their way down to the door at the end, which was even smaller.

“Is this where the watches are made?” asked John. “The Watchmaker must be a very compact fellow.”

“This is just our storeroom,” Bert replied as he knelt on the floor. “The Watchmaker is a very secretive creature. Verne has met him more often than I, and the only other thing I know about him is that he’s an old friend of Samaranth.”

“So he’s a Dragon?” asked Jack.

“I asked the same question,” said Bert, “and all he would say was that he had declined the promotion.”

“What are you doing down there?” said Charles. “I don’t think we can even get through that door.”

“It’s a voice-released lock,” Bert explained, leaning low to the small wooden door. “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?” he said in a baritone voice. A pause. Then he added, “The Shadow knows!”

There was a click, and then the wall—not the door, but the entire wall—swung open into a stone-lined room.

“The Shadow knows?” said John.

“I got the idea from some radio dramas I gave to the Cartographer,” said Bert. “It’s a safety feature.”

Inside, the walls were lined with small drawers and shelves laden with silver watches.

“Many of them resemble my own,” Bert said, “but it was an earlier model. Most of the rest look very similar to yours, John.”

“I’d like one of those, if I may,” said Jack.

“And I’d like to have one like yours, Bert,” said Charles. “If you don’t mind, that is.”

Bert selected two of the watches and handed them to the Caretakers. “Remember,” he said as he placed the watches in their open hands, “Believing is seeing.”

“Believe,” John, Jack, and Charles said together.

“Don’t go yet,” Bert said quickly. “I have something else for you.” He handed each of the companions another watch.

“Spares?” asked John. “In case we lose the first one?”

“No,” Charles said, understanding. “These are for our own apprentices, aren’t they?”

“Exactly,” said Bert. “There may be a time when you will want to know, without doubt, that someone will be there to come to your aid—as I have always counted on you. You’ll choose your apprentices when you give them the watch.

“But be very careful about whom you choose to give them to,” he continued. “They are the only means of telling whether or not someone is a true emissary or apprentice of the Caretakers. They cannot be duplicated and cannot be bought or sold—only earned. If they are stolen, they will crumble into dust. If they are sold, they will crumble into dust. If they are used for evil purposes, they will crumble into dust. But if they are cared for, and used properly, they have the potential to become much, much more, as the wearer earns the right to learn of their powers.

“But if nothing else, value them for being what they are—a symbol that the wearer belongs to the most honored and honorable gathering of men and women who have ever drawn breath.

“So,” he said in conclusion, “choose wisely, and choose well, whom you give them to. Your very life may depend on it.”

“So if Kipling is in league with Burton,” John said as they returned to the conservatory, “his watch probably crumbled to dust.”

Bert nodded. “That was all the evidence we needed that the wrong choices were being made, and we had a cuckoo in our midst.”

As they approached the conservatory, they could hear the noises of a heated discussion taking place. Quickening their pace, they rushed into the room and found that a new arrival had come to Tamerlane House.

“Ransom!” Jack exclaimed. “It’s very good to see you!”

“You made it!” said Ransom with obvious relief. “When I lost the Yoricks, I tried jumping back to this time, but it took a few tries to nail the date. It’s all been a botch of things from start to finish.”

“We’re just happy to see that you made it away in one piece,” said Charles.

“Yes, yes,” Ransom said distractedly. “It’s good to see you alive and well too, all of you. I’m sorry if I’m a bit brusque, but something terrible has happened. I have to show you, right now.”

“Whatever you need,” said Chaucer, gesturing broadly. “Please.”

Ransom cleared a space on the table and hefted a small case onto it. He popped open the twin latches on top and spread it open to reveal a curious device. It had coils and lenses, and two sets of frames that held slides in front of a turntable.

“It’s called a Hobbes stereopticon,” Bert explained as Ransom assembled the machine. “You can use a lens built into the side of the case to record events, and then it replays them for you later.”

“A camera

and

a projector,” said Jack. “Very nice.”

“Better than that,” said Bert. “It projects images and sound in three dimensions, and you can walk through them to observe a scene from every angle.”

“Do you have somewhere I can plug this in?” Ransom said, holding up the cord. “I used up the batteries making the recording.”

Jakob Grimm took the cord from Ransom and scrambled under one of the tables, searching for an outlet. “Got it,” he called after a moment. “Give it a go, Ransom.”

The philologist flipped a switch on the back of the stereopticon, and suddenly an incredible light show blazed to life. As Bert had said, the projection was displayed in all three spatial dimensions, filling the room. It was the coastline of a massive island, reduced to the size of a play set—except the tin soldiers were real, as was the battle they were witnessing.

Because the projector was on the table, the ground level of the film was at the Caretakers’ waist level. And so, as they walked around examining the scene, they looked like leviathans wading through the channel.

There was a great deal of destruction evident past the coastline. Fires raged, and in the distance, they could see buildings being toppled. According to Ransom, it got worse.

“The island is called Kor,” he said, looking back at John. “Do you know it?”

“It’s one of the oldest and largest in the Archipelago,” John said. “But what would cause all this destruction?”

“This is a declaration of war,” stated Ransom. “And a message to us all. If Kor can fall so easily, then it bodes ill for the rest of us. But there is something else.”

He pointed to several small objects on the surface of the water that disappeared as they watched. “Seven ships,” he said grimly. “Seven ships—and an army comprised of children—caused all this damage.”

“This is not an event in the future history,” said Twain, “but a continuation from one

past”

.

“Agreed,” said Bert. “This

must

be the Winter King.”

“Were those ships what they appeared to be?” John asked with a rising feeling of dread. “Surely they couldn’t be. Not here. Not

now!”

“The Dragonships lost in time,” said Jack. “From the Underneath, in 1926.”

Ransom grimaced. “I can’t say for certain, but I believe so. And I think he’s put them to use in places other than in the Archipelago.”

“Then why wait so long to begin the war here?” asked Jack. “The Summer Country has been at war for years—what was he waiting for?”

“He hasn’t just been waiting to make a move in the Archipelago,” said John. “He’s been planning to conquer them

both

all along.”

“This must be discussed with Artus and Aven,” Bert said as he paced the floor. “We need to go to Paralon.”

“That’s a good idea,” said John. “We need to see what Artus’s plans are. He needs to know, if he doesn’t already, that the war has finally come to the Archipelago.”

“I’m sorry, John, but you must remain here,” Chaucer said, almost apologetically. “As Caretaker Principia, there are responsibilities to attend to with the Gatherum.”

“Rose and Quixote should also stay,” said Bert. “Until we have a plan of action, it’s safer for them here. But I’d like Jack and Charles to come with me, to advise the king and queen.”