The Shadow Dragons (23 page)

Read The Shadow Dragons Online

Authors: James A. Owen

“Thank you,” replied the professor. “Bert used to refer to it as my ‘shield of charisma.’”

“She seemed to remember you,” said Quixote, “and very fondly at that.”

“And now you know one of the reasons that Bert could not be your guide,” said the professor. “The Queen of Entelechy would never have allowed him to pass.”

“Why not?” asked Rose.

“Because,” explained the professor, “when we came here before, the first words out of his mouth were, ‘You’re the largest woman I’ve ever seen in my life!’”

Both Johnson and Quixote groaned. “A terrible mistake,” said Quixote.

“Awful,” said Johnson.

“I don’t get it,” said Rose.

“You’re still very young,” Quixote told her, “but I will tell you what my grandfather wisely told me. Never, ever mention a woman’s size, or her age. Women are timelessly young and eternally beautiful.”

“Always?”

“Yes, always,” Quixote and Johnson said together.

“That’s part of the reason it took Bert eight hundred thousand years to find a wife,” said the professor. “No tact.”

The fifth gate was a trio of tall, spikelike rocks standing only yards apart from one another. The professor lit the tallow candles and instructed Archimedes to place the first one atop the center stone, the second on the stone to the right, and the third on the stone to the left.

“That’s it?” said Quixote.

“That’s it,” said the professor. “We may now pass.”

“What would have happened if we hadn’t placed the candles there?” asked Quixote.

The professor shivered and drew his coat closer. “I don’t even want to think about it,” he said. “I’ve been dead for a quarter century, and the idea

still

gives me nightmares.”

After the fifth island gate, they passed into what must have been night. The haze was replaced by complete darkness, and then, eventually, a night sky full of stars.

“Do you recognize any of them, Professor?” asked Rose. “I don’t see any of the constellations!”

“I don’t believe those are stars, per se,” said the professor in a hushed voice. “I believe those are the

dragons

themselves.”

It was a sobering, fantastic thought: that they were actually somewhere underneath thousands upon thousands of dragons— and so, the companions slept.

In a few hours, still under the night sky, they came to the sixth island.

Broad, with no hills or cliffs on the beaches, it was not a small island, but it had been completely overbuilt with temple after structure after edifice, until it was practically a city. And the city must have been deserted for countless years, because it was all but ruined.

The crumbling remains were more ancient than those they’d seen on Avalon, and even more ancient than the islands of the Underneath.

Standing among the ruins was a man, dressed in rags and clutching a book. He was staring up at the stars.

“Ah, me,” said the professor quietly. “It’s the last of the society pirates.”

They pulled the

Scarlet Dragon

onto the beach, and the professor took a few steps toward the man, who had not yet acknowledged their presence.

“Hello, Coleridge,” said the professor.

The man looked up at the mention of his name. He squinted at the boat on the beach, then at the passengers who were now standing in front of him.

“Sigurdsson?” he asked eventually. “Is that you? What are you doing here at the end of all that is?”

Rose wrinkled her brow at the question, but Quixote’s discreet touch on her arm signaled her not to speak. This man should be dealt with by the professor.

“This isn’t the end,” the professor said, his voice calm and soft. “This is just one more stopping place.”

“Dreams come true here, you know,” said Coleridge. “I’ve seen it happen. But no one told me . . .”

His voice trailed off, and he turned away again.

“No one told you what?” the professor asked.

“Nightmares come true here as well,” said Coleridge.

“Are you all right?” asked the professor.

“She took my arm,” Coleridge said simply, “but she let me go past. I had to come here. I had to see . . .”

“Come with us,” said the professor. “There’s no reason for you to stay. Do come. Please.”

The emaciated figure turned to look at him. “I cannot, for it may yet change. And there is nowhere else to go. There is nothing further. This was the last place in the world. This was the great city I saw in my vision, and it’s all a shambles. Destroyed.”

“You know it was once great,” said the professor. “You know how it began.”

“I did not know how it ended,” Coleridge said, looking up at the sky. “I did not know.”

He did not turn around again. The professor motioned for the others to get on the boat, and they sailed around and past the city.

“What a sad man,” said Quixote. “What happened to him?”

“On this island, dreams do eventually come true,” said the professor, “but true things are also real, and real things eventually fade. What we saw was the end of his particular dream.”

“What was this island called?” asked Rose.

The professor smiled, but it was a melancholy smile. “Xanadu,” he said. “It was called Xanadu.”

The waters after the Ruined City were placid, with no indication of currents or tides. Above them, disturbingly, the stars began to go out—but soon they realized it was because the light was coming up again. Strangely, it appeared that the sun was rising in the west—until they realized that it was not the sun at all, but the last of the seven island gates.

The island, emerald green with a thick blanket of grasses, was smaller than the last, and had no structures on it—only a ring of standing stones.

A Ring of Power, virtually identical to that on Terminus, save that the stones were larger.

They were pristine, and spread far enough apart that the areas between were paved with smooth stones. In the center was a long stone table draped with a crimson cloth, and seated at the table was a tall, silver-haired man.

As the companions approached, he rose to greet them. His tunic was also silver, shot through with crimson down the left side of his chest, and he was almost as tall as the Quintessence had been.

“Greetings,” said the professor. He introduced himself and the others, then asked if the tall man had a name.

“I am a star,” he said with an air of haughtiness, “or at least, I once was. I think I may be still, but it is difficult to say. However, when I was still in the sky, those who worshipped me called me Rao.”

“Is this a Ring of Power?” Rose asked. “Like the one used to summon the Dragons?”

Rao frowned. “Dragons? I know of none here who may be called to this place, save that I call them. And I would not deign to call Dragons, for they would not come for one such as I.”

“A Dragon would not come at the call of a star?”

“One, perhaps,” said Rao. “He would not look down upon me as the others might, for not having ascended. He himself chose to descend to the office of Dragon for the sake of a city, so he is, as you might think, different.”

“What was his name?” asked Rose.

“Samaranth,” said Rao. “But enough of this. Will you settle the dispute?”

“What dispute is that?” asked Quixote.

“There is a dispute between some of my children,” said Rao. “Have you come to arbitrate for them? To judge which is in the ascent, and which must descend?”

“We have not come to judge anyone,” said the professor. “We have merely come seeking someone who may have passed this way. He is called Madoc.”

Rao’s eyes narrowed. “None come here save that they fell. Are you saying you have come seeking one of the fallen?”

Before the professor could answer, Rose stepped forward again. “Not everyone must fall, great star,” she said, bowing her head respectfully. “We have come here of our own accord, and we did not fall. We flew.”

“Hmm,” Rao mused. “This I see, Little Thing. But take a caution—others before you have chosen a similar path, and fared the worse for it. Flying is not always ascending.”

“Are you one of the fallen?” Rose asked.

Professor Sigurdsson winced. That was not a question he thought would get a good response from a former star.

Strangely enough, Rao looked at her with gentleness, and even touched her head. “I was not,” he said. “I had not yet ascended, and thus did not have to choose. But soon, soon.”

“If I may,” said the professor.

“Little Thing,” Rao said bluntly. “Why have you come here?”

“We seek passage beyond your island,” said the professor, “in search of the man Madoc. May we pass?”

“You may not,” Rao said blithely. “None may pass save that one must stay. That is the Old Magic, and the old rule.”

“Then I offer myself,” said the professor. “I will stay, so that the others may pass.”

“No!” Rose cried. “You can’t!”

“That, dear Rose, is the other reason Bert could not come,” he replied. “Years ago, we turned back when another star made the same request. And we both knew it would be made again. A life for the passage. That’s the rule.”

“But we need you!”

“No,” he said gently, “you don’t. You needed me to get you to your father—and you’re nearly there. Quixote is your guardian—I was merely your guide.”

“We still have to convince him to repair the sword,” said Rose. “We can’t do that without you.”

“Rose,” the professor began.

“I’ll stay,” said a voice behind them. “I’ll do it.”

It was the portrait of Captain Johnson. “I’d be willing,” he stated, “if the fact that I’m essentially an oil painting doesn’t count against me.”

“Can you arbitrate?” asked Rao. “Will you arbitrate the disputes of my children?”

“I witnessed more than seventy pirate trials,” said Johnson. “I could give it a go, I suppose.”

“Little Thing,” Rao said, “this is acceptable to me. You shall stay, and the others may pass.”

Rose took the portrait from the boat, kissed it quickly, and handed it to Rao.

Quickly, before the star could change his mind, the companions hurried back to the boat and put her to sea.

“Thank you, Captain Johnson,” Rose called out.

“Farewell, Captain,” Quixote said.

“I’d rather have left the Caretaker,” said Archimedes. “There’s an entire

houseful

back in the Archipelago.”

“Remember,” Johnson called out, his voice growing faint as the island vanished behind the mist, “don’t trust Daniel Defoe!”

The Bargain

“Absolutely not,”

said Dickens. “It’s the most insane thing I’ve ever heard of in my life.”

“I concur,” said John. “He’s caused us more grief than almost anyone except for the Winter King himself, and he almost single-handedly brought about the Winterland when he tricked Hugo Dyson through that door. Letting him have asylum here, in Tamerlane House . . .” He paused and took a deep breath. “Well, it’s just unthinkable.”

“I think it’s worth at least a debate,” said Defoe. “He knows a great deal about the Shadow King’s plans.”

“Because he was his chief lieutenant until just a few hours ago!” said John. “We should consider him a prisoner of war, not a refugee seeking asylum.”

“I think he should be flogged,” said Shakespeare.

“But just yesterday,” Chaucer pointed out, “weren’t we debating whether or not his beliefs about the Archipelago and the

Imaginarium Geographica

were in fact superior to our own? That alone should change our perception of him.”

John rubbed his temples. This discussion was not progressing in a reasonable direction. “All right,” he said finally. “Bring him in.”

In one hand he held a hammer. The other was not a hand at all . . .

Richard Burton entered the conservatory, flanked by Nathaniel Hawthorne and Daniel Defoe. He grinned and nodded at John as he took a seat at the table.

“You should realize, Burton,” John began, “that none of us here trusts you in the least.”

“I don’t trust you any more than you trust me, John,” Burton said, “but desperate times make for strange bedfellows, and you don’t have to trust me—just my motives.”

“Which are?”

Burton raised his hands and smiled. “The same as they’ve always been,” he said simply. “No more secrets. My goals and those of the Caretakers have seldom been far apart—we just differ in how we approach them. But I’ve realized that the goals of the Chancellor are not mine—and whatever he is, he is not the man I would willingly serve. I believed he was. I was wrong.”

“Would you be willing to give us the information we need to defeat him?” asked Chaucer.

“I will share what I know,” said Burton.

“We haven’t yet decided whether to give you what you’re seeking,” said John, “but we’re considering it. In the meantime, you’re not to be left alone at any time. Either Charles and Fred will be with you, or Defoe and Hawthorne.”

“Fine.”

“You won’t be allowed to go near the docks,” John continued. “You must not leave Tamerlane House under any circumstance, and your men must remain within the bounds of their quarters. No exceptions.”

“Agreed.”

“Very well,” said John. “Do you have any questions?”

“Yes,” said Burton. “Where’s the kitchen? I’m starving.”

Charles, Defoe, and Fred took the first shift watching Burton, as the Caretakers continued the debate; and the kitchen was as secure a room as any other in Tamerlane House.

“You’re eating quite heartily for a prisoner of war,” said Charles.

“Asylum seeker,” said Burton, “depending on which way your friend’s wind blows.”

“Has anyone seen Jakob?” Hawthorne asked, peering around the corner. “I was supposed to help him with some notations an hour ago, and his cat is looking for him.”

“There’s a hall of mirrors in one of the rooms here,” Defoe said. “I think he wanted to go have a look at them, maybe see if there are any trapped princesses or lost treasures in them.”

“Very well,” said Hawthorne, sighing. “I’ll tell Grimalkin.”

“What the devil are you eating, Burton?” asked Charles.

“Aardvark,” he replied, chewing. “Will you have some? It’s delicious.”

“It looks a bit greasy to me,” said Charles. “Where did you get it? It isn’t something the Feast Beasts usually bring out for the banquets.”

“Oh, we brought them ourselves,” Burton said. “We didn’t want to impose on—or expect—your hospitality. The northern lands are crawling with them, and they’re easier to hunt than a baby deer.”

“How’s that?”

“Well,” explained Burton, tearing off another piece of flesh with his teeth, “do you know the old joke about how you can hunt deer with an apple and a hammer? Aardvarks are even less trouble than that, mostly due to their sensitive natures, and the fact that they’re very slow.”

Burton leaned over the table and spoke in a conspiratorial whisper. “To catch an aardvark,” he said, grinning, “all you have to do is find one, then start insulting it.”

“Really?” said Charles.

“Yes. Instead of running away, it gets offended and sits down, whining about how no one likes it and everyone just wants to be mean to aardvarks.”

“And then what?”

“Then, WHAM!” Burton exclaimed, slamming his fist to the table. “We wallop it with a hammer and marinate it in garlic and butter.”

“That’s positively barbaric,” said Charles.

“I

am

a barbarian,” said Burton, stroking his scarred cheeks with a bowie knife. “And besides, what else are aardvarks good for?”

“Good point,” said Charles.

The loss of their newfound friend was sobering to all four of the companions. In an unfamiliar place, Captain Johnson had been a comforting voice of reason and tact. Granted, being an oil painting, he had less to lose overall, but a life is a life, Sigurdsson told them, and his sacrifice was as meaningful as anyone else’s would be.

Past the island of the star, the waters grew still, but they remained cloudy, so it was difficult to estimate their depth. There were no other islands in sight in any direction, and only a smudge of color on the horizon, which hinted at thunderstorms. Other than continuing in the direction they were going, there was no strategy or plan of action they could employ. There was not even an expectation, said the professor, of what they might encounter next.

“Haven’t you been here before?” asked Rose.

The professor shook his head. “Remember, we only got as far as the star. When we had to leave someone behind just to go on, Bert and Ko and I decided that we’d gone far enough, and returned to the Archipelago.”

“So,” said Quixote, “we are truly journeying into an unknown region. This is truly the quest to end them all.”

“I know it’s just a turn of phrase,” said Sigurdsson, “but that really isn’t a comforting thought.”

“Professor,” Rose said gently. “Can you tell me what time it is?”

Professor Sigurdsson opened his mouth to reply, then saw the look on her face and stopped. He turned back to look out over the water and sighed. “Third time’s the charm, eh, Rose?” he said quietly.

He reached into his pocket and removed his silver pocket watch. Flipping the lid open, he took a quick glance and snapped it shut again, swallowing hard as he did so.

“How long have we been gone, Professor?”

“It took less than a day for Bert to fly us to Terminus,” he said matter-of-factly, “but more than a day to descend the falls. And from the time we discovered the

Aurora,

we have traveled for two full days. All told, we’ve been gone for just over a hundred hours.”

Rose closed her eyes as she realized what that meant. They were past the halfway mark that would allow the professor to return to Tamerlane House and the safety of the Pygmalion Gallery.

The professor reached an arm around her shoulders and gave her a comforting squeeze. “No time to worry about the trip back when we’ve yet to reach our destination, hey? Let’s see to that first, and we’ll worry about the rest when we have to.”

“Wall ho,” Quixote called out.

“Land ho, you mean,” said Archie.

“Land is land and a wall is a wall, and I know the difference between them,” Quixote retorted. “Look.”

In the near distance, what they had assumed to be storm clouds on the western horizon was now revealed to be more substantial than clouds, and taller besides.

It was, as Quixote said, a wall.

As high as the waterfall at the world’s edge had been, the wall was tall, and it stretched away in both directions, north and south, to the vanishing point on each horizon.

“I wonder what’s on the other side?” Professor Sigurdsson mused, squinting as he looked up for a glimpse of the wall’s summit. “I wonder if there’s a way over?”

“This is how people are chosen as Caretakers of an atlas like the

Geographica,”

Quixote said to Archimedes. “They can’t escape it. It’s in their blood.”

The wall was so massive that even once they had sighted it, it took another two hours to reach the base. It stood on a narrow beach that was perhaps thirty feet wide and, as far as they could tell, ran the length of the wall. It was as if an infinite barrier had been placed on an equally infinite sandbar.

They pulled the

Scarlet Dragon

into the shallows and clambered out to examine the wall. It was made of stones that were placed so closely and precisely that Quixote could not get his sword point between any two of them.

“Impressive,” he said with grave sincerity. “I would not have believed such a wall was possible.”

“I can’t find a top,” called Archie, who was spiraling back down to the others. “I could fly higher, but the air was getting too thin to keep me aloft.”

“Is this the end of our journey, Professor?” asked Rose. “If we can’t get over it or through it, then how do we go on?”

“It is the end of all that is,” a voice said from farther down the beach. The words were spoken calmly, but were tinged with menace, and perhaps . . . fear?

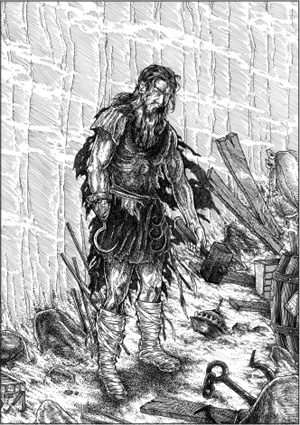

The companions turned around to see a man standing about twenty feet behind them. In one hand he held a hammer. The other was not a hand at all; his arm ended in a hook, which was tarnished and rusty. He was heavily bearded, and his clothing was in tatters. And on his face was a look that was almost indescribable, a mix of fury and what might be relief.

“Hello, Father,” said Rose. “It’s nice to finally meet you.”

There was none among them, other than the professor, who might say how the fall over the water’s edge had changed the man called Madoc.

Rose had seen him only once before. At the time he was known as Mordred; he had just tried to kill her uncle Merlin, and had lost his hand to her cousin Arthur. Quixote had also never seen him, but knew of him only through stories about the Winter King, as his enemies had called him. Archimedes had known him when he was still called Madoc, but that had been many centuries earlier. Only Professor Sigurdsson had seen him as the man he was now—and that was moments before Madoc, Mordred, the Winter King, had killed him in his study.

Madoc’s hair and beard were long and greasy. His arms were thick and corded with muscle, and he watched the new arrivals with suspicion. Slowly he paced back and forth across the width of the sand, never taking his eyes off them. Finally he decided to speak—to the owl.

“Hello, Archimedes,” he said. “You’re looking well.”

“You’re not, Madoc,” Archie replied, lighting onto Quixote’s shoulder. “You look like you’ve been hit by a train.”

“Actually, I was dropped over a waterfall,” said Madoc, “but the net result is probably the same.”

“How did you bypass the gates, then?” asked the professor. “And once below, why didn’t you try to return to the Archipelago?”

“I was compelled,” Madoc said, “and I remain so. I briefly thought of trying to repair that ship, the

Aurora,

but I was unable to even pause to appraise the vessel’s damage. I may have been swimming, or walking, or otherwise moving perpendicular to the waterfall, but make no mistake—I was always falling, and am falling still.”

“Until you reached this wall,” said the professor.

“Yes,” said Madoc. “Until I came here. As far as I can determine, it is endless. I spent years doing nothing but walking, first in one direction, then the other. After a while, I began to hallucinate. I dreamed that as I slept, all my progress was undone, and I had been returned to the place I started. Even if that had been true, there was no way to know for certain.

“It’s impossible to climb—believe me, I’ve tried. I wasted a year on

that.

Then I considered trying to dig my way through, but other than this,” he said, holding up his hook, “I had nothing that was capable of even scratching it. I built a forge and created several tools, using metals I’ve scavenged from the beach, but they’ve all proven too soft for the stone as well. That was almost two years ago. I’ve spent all of my time since planning my revenge.”