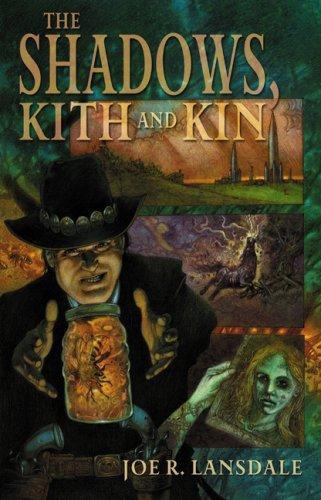

The Shadows, Kith and Kin

Read The Shadows, Kith and Kin Online

Authors: Joe R. Lansdale

| The Shadows, Kith and Kin | |

| Joe R. Lansdale | |

| Subterranean Press (2007) | |

| Értékelés: | **** |

| Címkék: | Fiction, Horror |

The endlessly inventive mind of Joe R. Lansdale whips up yet another batch of stories to amaze, surprise, and entertain you. His new offering covers a lot of territory, producing what may be his best short story collection yet. One tale concerns an East Texas mule race in the early 1900s that proves to be an unexpected turning point and learning experience for the main character, a lifelong loser. It also chronicles the unusual circumstances of the race, which include a friendship between a rare white mule that can run like the wind, and his friend, a loyal, spotted pig. Another tale drops us into the disturbed mind of a mass murderer and his friendship with the shadows. Two others stories reintroduce us to the supernatural adventures of Reverend Rains, the flawed hero from Lansdale's cult favorite novel, Dead in the West. Here ghouls prowl and werewolves howl. There's a poetic collaboration with Melissa Mia Hall about the nature of loneliness and loss that echoes back to science fiction stories of an earlier time, as well as a famous, award winning novella reprinted here for the first time in several years about a clutch of unusual crime solvers. Read about a world where the dead almost rule, and venture into an alternate universe that is the background for perhaps the strangest tale of all, an adventure concerning an earnest and horny steam shovel named Bill, and his challenge to do the right thing at all costs. It's the usual wild and crowd pleasing display of what has become a subgenre of modern literature as only Joe R. Lansdale can present it: Tales Lansdalien. Welcome to his world.

THE SHADOWS, KITH AND KIN

"…and the soul, resenting its lot, flies groaningly to the shades."

The Aeneid, by Virgil

There are no leaves left on the trees, and the limbs are weighted with ice and bending low. Many of them have broken and fallen across the drive. Beyond the drive, down where it and the road meet, where the bar ditch is, there is a brown, savage run of water.

It is early afternoon, but already it is growing dark, and the fifth week of the storm raves on. I have never seen such a storm of wind and ice and rain, not here in the South, and only once before have I been in a cold storm bad enough to force me to lock myself tight in my home.

So many things were different then, during that first storm.

No better, but different.

On this day, while I sit by my window looking out at what the great, white, wet storm has done to my world, I feel at first confused, and finally elated.

The storm. The ice. The rain. All of it. It's the sign I was waiting for.

––

I thought for a moment of my wife, her hair so blonde it was almost white as the ice that hung in the trees, and I thought of her parents, white-headed too, but white with age, not dye, and of our little dog Constance, not white at all, but all brown and black with traces of tan; a rat terrier mixed with all other blends of dog you might imagine.

I thought of all of them. I looked at my watch. There wasn't really any reason to. I had no place to go, and no way to go if I did. Besides, the battery in my watch had been dead for almost a month.

––

Once, when I was a boy, just before nightfall, I was out hunting with my father, out where the bayou water gets deep and runs between the twisted trunks and low-hanging limbs of water-loving trees; out there where the frogs bleat and jump and the sun don't hardly shine.

We were hunting for hogs. Then out of the brush came a man, running. He was dressed in striped clothes and he had on very thin shoes. He saw us and the dogs that were gathered about us, blue-ticks, long-eared and dripping spit from their jaws; he turned and broke and ran with a scream.

A few minutes later, the sheriff and three of his deputies came beating their way through the brush, their shirts stained with sweat, their faces red with heat.

My father watched all of this with a kind of hard-edged cool, and the sheriff, a man Dad knew, said, "There's a man escaped off the chain gang, Hirem. He run through here. Did you see him?"

My father said that we had, and the sheriff said, "Will those dogs track him?"

"I want them to they will," my father said, and he called the dogs over to where the convict had been, where his footprints in the mud were filling slowly with water, and he pushed the dog's heads down toward these shoe prints one at a time, and said, "Sic him," and away the hounds went.

We ran after them then, me and my dad and all these fat cops who huffed and puffed out long before we did, and finally we came upon the man, tired, leaning against a tree with one hand, his other holding his business while he urinated on the bark. He had been defeated some time back, and now he was waiting for rescue, probably thinking it would have been best to have not run at all.

But the dogs, they had decided by private conference that this man was as good as any hog, and they came down on him like heat-seeking missiles. Hit him hard, knocked him down. I turned to my father, who could call them up and make them stop, no matter what the situation, but he did not call.

The dogs tore at the man, and I wanted to turn away, but did not. I looked at my father and his eyes were alight and his lips dripped spit; he reminded me of the hounds.

The dogs ripped and growled and savaged, and then the fat sheriff and his fat deputies stumbled into view, and when one of the deputies saw what had been done to the man, he doubled over and let go of whatever grease-fried goodness he had poked into his mouth earlier that day.

The sheriff and the other deputy stopped and stared, and the sheriff said, "My God," and turned away, and the deputy said, "Stop them, Hirem. Stop them. They done done it to him. Stop them."

My father called the dogs back, their muzzles dark and dripping. They sat in a row behind him, like sentries. The man, or what had been a man, the convict, lay all about the base of the tree, as did the rags that had once been his clothes.

Later, we learned the convict had been on the chain gang for cashing hot checks.

––

Time keeps on slipping, slipping. . . Wasn't that a song?

––

As day comes I sleep, then awake when night arrives. The sky has cleared and the moon has come out, and it is merely cold now. Pulling on my coat, I go out on the porch and sniff the air, and the air is like a meat slicer to the brain, so sharp it gives me a headache. I have never known cold like that.

I can see the yard close up. Ice has sheened all over my world, all across the ground, up in the trees. The sky is like a black-velvet backdrop, the stars like sharp shards of blue ice clinging to it.

I leave the porch light on, go inside, return to my chair by the window, burp. The air is filled with the aroma of my last meal: canned Ravioli, eaten cold.

I take off my coat and hang it on the back of the chair.

––

Has it happened yet, or is it yet to happen?

Time, it just keep on slippin', slippin', yeah it do.

––

I nod in the chair, and when I snap awake from a deep nod, there is snow blowing across the yard and the moon is gone and there is only the porch light to brighten it up.

But, in spite of the cold, I know they are out there.

The cold, the heat, nothing bothers them.

They are out there.

––

They came to me first on a dark night several months back, with no snow and no rain and no cold, but a dark night without clouds and plenty of heat in the air, a real humid night, sticky like dirty undershorts. I awoke and sat up in bed and the yard light was shining thinly through our window. I turned to look at my wife lying there beside me, her very blonde hair silver in that light. I looked at her for a long time, then got up and went into the living room. Our little dog, who made his bed by the front door, came over and sniffed me, and I bent to pet him. He took to this for a minute, then found his spot by the door again, laid down.

Finally I turned out the yard light and went out on the porch. In my underwear. No one could see me, not with all our trees, and if they could see me, I didn't care.

I sat in a deck chair and looked at the night, and thought about the job I didn't have and how my wife had been talking of divorce, and how my in-laws resented our living with them, and I thought too of how every time I did a thing I failed, and dramatically at that. I felt strange and empty and lost.

While I watched the night, the darkness split apart and some of it came up on the porch, walking. Heavy steps full of all the world's shadow.

I was frightened, but I didn't move. Couldn't move. The shadow, which looked like a tar-covered human-shape, trudged heavily across the porch until it stood over me, looking down. When I looked up, trembling, I saw there was no face, just darkness, thick as chocolate custard. It bent low and placed hand shapes on the sides of my chair and brought its faceless face close to mine, breathed on me—a hot languid breath that made me ill.

"You are almost one of us," it said, then turned and slowly moved along the porch and down the steps and right back into the shadows. The darkness, thick as a wall, thinned and split, and absorbed my visitor; then the shadows rustled away in all directions like startled bats. I heard a dry, crackling leaf sound amongst the trees.

My God, I thought. There had been a crowd of them.

Out there.

Waiting.

Watching.

Shadows.

And one of them had spoken to me.

––

Lying in bed later that night I held up my hand and found that what intrigued me most were not the fingers, but the darkness between them. It was a thin darkness, made weak by light, but it was darkness and it seemed more a part of me than the flesh.

I turned and looked at my sleeping wife.

I said, "I am one of them. Almost."

––

I remember all this as I sit in my chair and the storm rages outside, blowing snow and swirling little twirls of water that in turn become ice. I remember all this, holding up my hand again to look.

The shadows between my fingers are no longer thin.

They are dark.

They have connection to flesh.

They are me.

––

Four flashes. Four snaps.

The deed is done.

I wait in the chair by the window.

No one comes.

As I suspected.

The shadows were right.

You see, they come to me nightly now. They never enter the house. Perhaps they cannot.

But out on the porch, there they gather. More than one, now. And they flutter tight around me and I can smell them, and it is a smell like nothing I have smelled before. It is dark and empty and mildewed and old and dead and dry.

It smells like home.

––

Who are the shadows?

They are all of those who are like me.

They are the empty congregation. The faceless ones. The failures.

The sad empty folk who wander through life and walk beside you and never get so much as a glance; nerds like me who live inside their heads and imagine winning the lottery and scoring the girls and walking tall. But instead, we stand short and bald and angry, our hands in our pockets, holding not money, but our limp balls.

Real life is a drudge.

No one but another loser like myself can understand that.

Except for the shadows, for they are the ones like me. They are the losers and the lost, and they understand and they never do judge.

They are of my flesh, or, to be more precise, I am of their shadow.

They accept me for who I am.

They know what must be done, and gradually they reveal it to me.

The shadows.

I am one of them.

Well, almost.