The Shameful Suicide of Winston Churchill

Read The Shameful Suicide of Winston Churchill Online

Authors: Peter Millar

of

WINSTON CHURCHILL

PETER MILLAR

Title Page

Praise

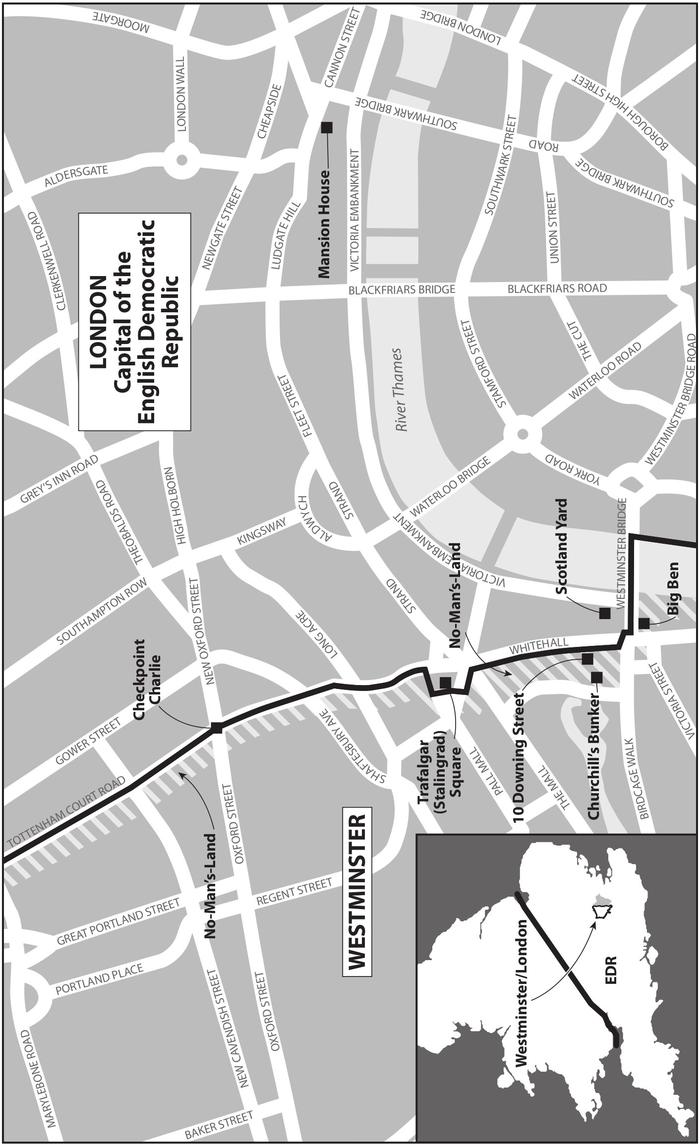

Map

OVERTURE: Zero Hour

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Author’s Note

About the Author

Copyright

‘Should the German people lay down their arms … over all this territory, which, with the Soviet Union included, would be of enormous extent, an Iron Curtain would descend.’

Joseph Goebbels

Das Reich

newspaper, 23 February 1945

‘I must tell you that a socialist policy is abhorrent to British ideas on freedom. There is to be one State, to which all are to be obedient in every act of their lives. This State, once in power, will prescribe for everyone: where they are to work, what they are to work at, where they may go and what they may say, what views they are to hold, where their wives are to queue up for the State ration, and what education their children are to receive. A socialist state could not afford to suffer opposition – no socialist system can be established without a political police. They would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo.’

Winston Churchill

Election address, 1945

‘History will be kind to me, because I intend to write it.’

Winston Churchill, 1948

‘… though God cannot alter the past, historians can; it is perhaps because they can be useful to Him in this respect that He tolerates their existence.’

Samuel Butler

Erewhon Revisited

, 1901

Downing Street, London, September 1949

The house that sat at the heart of the world had no name, just a number like any other. And had long since been reduced to rubble. Like every other. War was the real great leveller. But even in destruction the semblance of similarity between this house and any other was false.

From the centre of a global web of countless colonies, domains and dependencies, a local filigree network spread beneath the ground. Beneath the fallen masonry, the eighteenth-century brickwork that had crumbled into dust, the shards of marble from staircases and fireplaces, emerging from what once had been cellars for wine and coal, a labyrinth of debris-littered tunnels still survived, leading like a choked artery to the

crippled

body politic’s residual nerve centre, which stubbornly still functioned even though its life support system was slowly, surely, failing.

Even here the dust permeated; the last tangible traces of grandeur ground to grit stuck to the skin and irritated the eyes. Dust to dust. The old man closed his eyes to shut out reality. But he could not shut out the noise, though it was more felt than heard: a dull, persistent rumbling, broken by intermittent juddering thuds. As if the earth was shaking. As well it might.

All eyes were on him, if only surreptitiously. In the specially designed, one-piece, grey pinstriped ‘siren suit’ that he referred to as his ‘rompers’, he had so long resembled a big, bumptious,

cigar-puffing baby. But not any more. He looked shrunken, wizened, as though he had surrendered at last, if only to his years. He no longer paced, not even with the aid of his stick, but emerged from his sleeping quarters to stalk the Map Room sombrely, oblivious to the flickering light from the caged safety light that with every advancing shock wave swayed above his head like on the deck of a ship in a storm.

The telephone lines were silent now, the red, white and black on the centre table no longer linked their attendant lieutenant colonels to distant command centres that had long since

collapsed

. In the radio room pretty girls with drawn faces and tremblingly rigid upper lips, eavesdropped on the end of the world: a high-pitched, scratchy, chimpanzee chatter of distant voices interspersed with crackle and the soaring, dipping banshee howl as they chased up and down the frequencies for the ghosts on the airwaves. In an ever more alien ether.

Tortuously

twisted hairclips beside the mugs of half-drunk, cold, weak tea testified to the terrible tension that gnawed at their innards.

Occasionally, increasingly rarely, contact would be made. And held. Sometimes, only sometimes, the voices in the ether asked for orders. The answer they were given was always the same. The same as it had been for days now: ‘Hold on as long as you can.’ No one dared address the follow-up: ‘And then?’ Just as no one dared approach the old man. The rule had, in any case, always been ‘speak when you’re spoken to’. And he hadn’t spoken now for more than twenty-four hours. The man famed for holding forth for hours on end, with no more

audience

than a pet dog, had been reduced to a sinister silence. At least in what passed for public.

In recent days he had retired only rarely to the little bed in his cramped quarters off the Map Room, armed as ever

with whisky, though even that was now in short supply. The champagne had long gone, the empty magnums of Pol Roger a mocking memory of better times. He slept, if at all, for no more than an hour or two at a time, emerging, glass in hand, to stare at the ‘big board’, watching bleakly as one piece after another was removed. Like a giant chess game. An endgame.

Except that while the enemy had been playing chess, he had been playing poker. Bluffing to the end. He had taken the big gamble, and seen the cards fall against him, just as they had done more than thirty years ago at Gallipoli, on the Turkish coast. In another war. Another lifetime. Lady Luck favoured those who dared, he had believed. But Lady Luck was just another tart. All he had got was the quick fuck. And now it was his back against the wall. He almost smiled at the coarse metaphor, but the time for smiles was past. As was the time for metaphors.

Fine phrases had not been enough. The blood had run dry. The sweat had been wasted, the toil in vain. There was nothing left but the tears. He had been defeated on the beaches, defeated on the landing grounds, defeated in the fields and in the streets. He, and those who had put their trust in him.

On the wall next to his bed the great map of the British Isles, with its shoreline, cliffs and beaches colour-coded according to their defensiblity, was defaced with the string and pins that charted the inevitable encroachment of the red tide.

In the Map Room itself the great geophysical charts that had once allowed him to watch his erstwhile allies’ expansion from the depths of the steppes to Berlin and beyond had been torn down long before they became his enemies and reached the English Channel. The scale had changed by then; the global had become personal. The map now was one with which he had been familiar all his life – the map of London – one on

which he had hoped he would never have to play the terrible game of war, let alone see his playing chips reduced to this. The markers with the familiar emblems of proud regiments represented little more than remnants, huddled together like sheep in a pen.

He could barely bring himself to think of the reality they represented, the reality above his head: London’s familiar streets transformed into a battleground with bus shelters turned into barricades, taxi ranks become tank traps, the last ditch defenders – little more than boys some of them –

crouching

with bazookas behind Regency balustrades and East End dustbins, from Peckham to Piccadilly, in burnt-out pubs and the smoking remains of Pall Mall clubs. All equal at last, in their final hours.

With a brusque, angry gesture he swept the markers away.

The old man took the smouldering stub of his fat Havana cigar reluctantly from his mouth and ground it out on the

fine-tooled

leatherwork of his desk. Then he stood for a moment transfixed by the sight of the crumbling ash. Ashes to ashes. Like the taste in his mouth. His heart was heavy as he took down the Sam Browne belt and the holstered semi-automatic Colt that had served him so well. He knew what he had to do. There was only one way out now.

The girls on the silent switchboard peeked out silently as he pulled on his khaki greatcoat and his peaked cap. Then, leaning heavily on his stick, he made for the door that he had not used for nearly three weeks. The door that led upstairs, to the world above, to Armageddon.

One of the girls made to go and help him, but her colleague held her back with a restraining arm and tears in her eyes. No, her look said, though like the rest of them she said nothing. If words failed even him, what could anyone else say? Let him

go, her eyes said. To do what he has to do. It’s over. For all of us. Nonetheless, the girl got up to go and wash her face, to dry her tears.

Behind the eyes that held back tears, there was, for the first time, also fear. They had heard the stories, of the butchery, the wanton savagery and the wholesale rape. Of the women in Dover, Hastings and Brighton who had blackened their faces with coal dust, dressed in drab overcoats and pulled their grandfathers’ darned woollen socks over their legs. And still had not been spared.

As the old man passed them, those he was leaving to their own fate, he wondered if he ought to make a gesture, to say goodbye. But he no longer knew how to face them. He prayed they would escape the worst, though he doubted it.

Disguises would do him no good. His face was familiar the world over. Even in the benighted ranks of the ignorant enemy. He let his hand reach inside the greatcoat, settle on the familiar pistol grip. Then he turned the handle on the

reinforced

steel door and took the first step on the staircase that led up to what was left of the world, and to his own

appointment

with destiny.

And those that watched him go, or for form’s sake pretended not to notice, knew that what they were witnessing was a death. Not the death of a man – what was one more amid so many? – but of an empire. And an era. From now on there would be a new world order.

Already the world above looked changed beyond

recognitions

,

a world turned on its head. His tired, bloodshot eyes blinked beneath the weary wrinkled lids and smarted from the cordite in the acrid air. A cacophony assaulted his ears, of screaming sirens, howling aircraft engines, the staccato chatter of distant machine-gun fire and the dull oppressive

persistent percussion of artillery. Closer to hand, he could hear the mechanical screech of cogs and cranks that hauled heavy armour across the fallen brickwork and shattered Portland stone facades, the T-34s and the new, monstrous Stalin tanks, remorselessly grinding their way over the ruins. Coming closer by the moment.

Stumbling, frightened – he admitted it to himself as he would have done to no one else – he peered through the

dust-choked

air past the remnants of Downing Street to the ruins of

Whitehall, then turned his gaze in the other direction. Winston Spencer Churchill, First Lord of the Treasury, 41st Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Commander-in-Chief of imperial forces drawn from five continents, the man who had once boasted that the British empire and its

Commonwealth

might last a thousand years, wiped a tear from his eye. As he stumbled towards what had once been the green oasis of St James’s Park, its trees long since felled for firewood, he hefted the weighty revolver in his hand. He knew he no longer had a choice.

Behind the plinth of the Clive statue, peering over the toppled bronze statue of the empire’s first great hero, the

insignificant

little figure, with her woolly hat and tear-streaked cheeks could not believe her eyes but the image remained imprinted on her retinae forever.