The Shell House (17 page)

‘Someone you can look at the stars with and swim in the sea with at dawn?’

‘Yes,’ Jordan said. There was a pause, then: ‘That’s why I told you. To see if you like stargazing.’

Another expectant silence; Greg’s vocal cords felt numbed. He cleared his throat, stalled: ‘So it’s only your dad who knows, then?’

‘Oh no,’ Jordan said, matter-of-factly. ‘We decided it was best to tell Mum and Michelle as well.’

‘

Michelle

knows?’ For one squirming second, the idea of telling Katy floated into Greg’s head.

‘Why not?’

Greg threw out both hands—

It’s obvious

. But it was not obvious to Jordan.

‘It’s like—when someone nearly dies, when Michelle nearly did, it puts things into perspective,’ Jordan explained. ‘What does anything else matter, as long as we’re all alive and together? What’s the point of hiding things? I didn’t want Michelle asking me about girlfriends—didn’t want to pretend. It’s better that she knows. And she’s mature enough to be fine about it.’

‘Hang on a minute. Do you mean to say—that time I came round for Michelle’s birthday, and last night—they were all looking at me as your boyfriend? A candidate for your Special Someone?’

‘If you want to put it like that. They like you.’

Greg huffed out his breath. ‘Oh, great!’

‘Why does that annoy you?’

‘You really need me to spell it out? Your mum said I could stay the

night

, for Christ’s sake! Is that what you meant just now, about going round yours? Come and stay the night? What, share your bed, with everyone’s approval? I suppose even your little brother knows? You wouldn’t want to leave anyone out of confession time—’

‘Not Mark, of course not, he’s much too young to understand. And Mum didn’t mean share my bed. They’re open-minded, but not

that

open-minded.’ Jordan was starting to assume the closed-off look he often wore at school:

Private, keep out.

‘Why are you annoyed? I’m not putting any pressure on you. I don’t want anything unless you want it too.’

‘It’s obvious, isn’t it? Everyone knowing. Everyone watching.

Christ

—’

‘You don’t believe in him.’

‘No, and you know what?’ Greg shifted his feet. ‘I don’t believe this, either. Any of it.’ Abruptly he stood up. ‘Forget it—just forget it, this whole conversation!’

Jordan looked up at him: reproachful, dismayed. ‘You know that’s impossible.’

‘Not for me it isn’t.’ Greg shook his head, thrusting his hands into his jeans pockets. ‘See you.’

‘Greg—’

‘Leave me alone!’

Greg turned and walked away fast, slamming through double doors, hearing them clack shut behind him in the emptiness of the corridor. He did not look back.

The Intensive Care sign loomed in front of him; he was back in the maze. He pushed open the door and marched in. By the far window, he saw Dean Brampton’s mother slumped in a chair with her back to him, beside the farthest bed. Dean lay on his back, his face still, so young—just a desperately injured boy, not the mouthy yob Greg knew.

A nurse came towards him, both hands held up:

Stop

. She shepherded Greg back into the waiting area, out of sight.

‘What do you want? I can’t let you into the ward. Mrs Brampton’s very upset.’

‘I want to know how he is. Dean.’ Greg’s voice came out gruffly.

‘You’re not family—’

‘No.’ Greg couldn’t bring himself to say

friend

either, repeating Jordan’s lie. ‘But I want to know.’

‘Well, he’s very poorly. As comfortable as can be expected. Not much change. That’s all I can tell you.’

Nothing, in other words. Nothing, wrapped up in hospital euphemisms.

‘He’s not paralysed, is he? Will he be able to walk?’

‘I’m sorry, it’s too early to tell.’

‘OK. Thanks.’

‘Go straight back to Reception and out that way,’ the nurse told him. ‘You shouldn’t be wandering round the hospital at this time of night.’

The ward doors opened to his shove. He half-wanted Jordan to have followed him, and was both relieved and disappointed that he had not. The corridor stretched both ways, polished and blank. Greg grimaced, clenching his fists till his nails dug into his palms; he bit his lip hard, wanting to hurt someone. Himself, most of all.

‘Jesus

Christ

!’

He had to get out of here. He walked fast, blindly, hardly noticing where the signs led him, till he found himself back at Accident and Emergency, with double doors leading out. The cool air welcomed him. He started to jog up the long entrance drive, then settled into a steady run, the rhythm of his feet pushing all thought from his head. A blur of lights from the streetlamps danced in his head, traffic noise snarled at his heels; he ran till his teeth ached and his lungs were sore. He had to keep running.

‘I’m recommending you for a week’s home leave,’ Captain Greenaway had told Edmund, ‘during which time I expect you—in fact I order you—to put this behind you, and come back with your mind properly on the job.’

Edmund stood in the garden at Graveney Hall, looking over the ha-ha. It was April; the air smelled of spring and new growth; the trees were bursting into leaf. A mockery.

Alex was dead.

Alex was a name on a Casualty list.

Alex had Died of Wounds.

Alex was buried in a shallow grave near mine-workings.

Alex was nowhere.

Alex had gone, and God had not kept his bargain.

God, if he had listened at all, had shown Edmund that he would not be bargained with. He had taken revenge on Alex—not just by letting him die, but by making him suffer a protracted, agonized death. Reducing him, at the end, to something less than human: a tormented animal, twisted and distorted with pain. Surviving the first night against all expectations, Alex had lasted two more, merely to give Edmund false hope and to endure two days and nights of torture from his internal injuries. Unable to bear it, Edmund had begged the nurse for morphine until at last Alex, never once recognizing him, had slipped away to wherever he was now.

‘His suffering’s over now,’ the nurse had said, soft-voiced, drawing the sheet over Alex’s face.

Somehow, in that squalid front-line hospital that reeked of pus and excrement and disinfectant, she managed to keep herself neat, her apron and cuffs shining white. Edmund looked at her through a dazzle of tears. She might as well have been speaking Chinese for all the sense her words made to him.

At the burial service he stood rigid and cold, unable to let himself think or feel. Six others were buried at the same time: two officers, three privates and a sergeant. A brief, impersonal prayer did for all. When it was finished Edmund was overcome by a fit of shuddering, feverish and violent. Back in the dug-out, Faulkner brought him hot coffee laced with whisky. Afterwards he drank the best part of a bottle of whisky, seeking oblivion, and found it temporarily in a drunken sleep.

For the next interminable days he was half-mad with grief. People spoke to him and he did not hear. He felt his eyes rolling in their sockets like marbles, his brain was a scrambled mess of disconnected wires. He couldn’t eat, couldn’t sleep. He courted death: he took risks, stuck his head above the parapet, waiting for a German sniper to despatch him, sending him after Alex. No rifle-crack obliged. He was sentenced to live, if this could be called life. He must continue to fight a war whose outcome meant nothing to him. He would gladly have welcomed the chance to accompany his unit into some hopeless, doomed attack that would obliterate the lot of them. A futile death would be the fitting end to his futile life.

After a few days of this, Captain Greenaway called Edmund into his dug-out and told him to remember his responsibilities. ‘I know you’ve taken Culworth’s death very hard, as indeed we all have. He was one of our best officers, and I liked him immensely. But you can’t let yourself dwell on it. You’ve become slack in your duties—you’re letting your men down. They need leadership, not this mawkish lingering on something that can’t be changed.’

Put this behind you. Be a man. Smarten up.

Easy commands; impossible to obey. The stark fact of Alex’s death was constantly before him; there was nothing else. After Alex, an empty void, an airless vacuum. What was the point of going on breathing? Yet he must, because his body stubbornly insisted on taking in oxygen, circulating blood, repairing damaged cells. Was it possible simply to will yourself to die, tell your body to stop functioning? On the front line he had seen how vulnerable human flesh was: how blood, brains, intestines could be spilled and scattered, how fit young bodies could quickly become festering flyblown gobbets for rats to feed on. A shell-blast, a bullet, a bayonet wound could do that. How could his own body remain healthy, oblivious to his reeling brain?

Since God had let him down, Edmund would believe in Alex. Cling to him. Remember every word he had said, every look, every touch. God had not agreed to the bargain and Edmund was freed from his part in it. If God had obliged, he would be faced with the impossibility of keeping his promise. He now had no choice to make, and permission to love Alex for ever. He felt ashamed of how easily he had been tricked into betrayal in a moment of blind repentance. It was another instance of God’s cruelty.

Here at Graveney it was as painful to remember Alex alive as it was to think of his miserable death. The greening fields and trees reminded Edmund of the week they had spent at the farmhouse in Picardy, talking of their future. He wandered along to the Pan statue. Pan, on his pedestal, raised his pipes to his lips; around him cavorted three naked infants carrying a garland of leaves. As a child Edmund had liked Pan, with his dancing goat legs and the two small horns sticking out of his hair. He had pretended to hear Pan’s flutey music, had looked out of his bedroom window in summer dusks, imagining he might see the god and his cherubic attendants leap off their pedestal to cavort round the fountains and flower-beds. Pan had been more interesting than God; he had more fun, and made no demands. Now he was frozen in a dance of pointless merriment, mocking Edmund and his sorrow, as everything seemed to.

His parents, inevitably, had decided to add to his torment by arranging a dinner party for this evening. He closed his eyes, thinking of the ordeal awaiting him. The Fitches, of course, were the principal guests. Philippa would be coiffed and simpering, her parents watching avidly for any symptom of concealed passion on Edmund’s part. His own mother had already hinted that this leave, coming unexpectedly, would be the ideal time to

put things on a proper footing

, as she expressed it. She meant that he should propose to Philippa, engage himself to her. It would give everyone something nice to look forward to as a change from this horrid war, she said. Not that the horrid war made much impression that Edmund could see on Graveney Hall. Dinner parties were a little less frequent, the range of dishes less extensive, and the table-talk was likely to refer to the latest

Times

headlines, with deferential nods towards Edmund, representative of England’s brave soldiers; but otherwise daily life went on as normal, fixed in its routines. Other big houses had been transformed into convalescent hospitals, but Graveney Hall kept itself aloof, isolated on the edge of the forest like a remnant of a past age. The century was moving on, the war taking place out of Graveney’s sphere.

Edmund would not marry Philippa, would not sire an heir for Graveney. He had been released from his duty, and Alex had been the price. But only he and God knew that.

Slowly, reluctantly, he walked across the garden and up the steps, indoors and upstairs, though he could hear the voices of guests in the drawing room, where they had gathered to drink sherry. In his room he looked at himself in the cheval mirror, straightened his tie, gazed into the frightening blanks of his own eyes. Then he lay on his bed and took out his pocket-book, unwrapping it from the scrap of oilskin he used to protect it from dampness. Tucked inside the notebook he kept the letters Alex had written him. There were not many, as for most of their time they had been together with no need to write letters, though sometimes in the front line, cramped and constrained by the presence of others, they had written notes and slipped them into each other’s hands or pockets. Alex’s crumpled notes, too, were in the notebook. It had occurred to Edmund that if he were killed, these letters and notes, plainly love-letters, would be sent home along with his other belongings, and his secret would be known; but he could not bear to part with them, and that meant always carrying them on his person, since there was nowhere safe to hide them. Now they were his most precious possessions.

He knew their contents almost by heart. Alex was there in the sweep of black ink, in the splaying of fountain-pen nib, in the characteristic letter

g

s, in the swoop-tailed capital

A

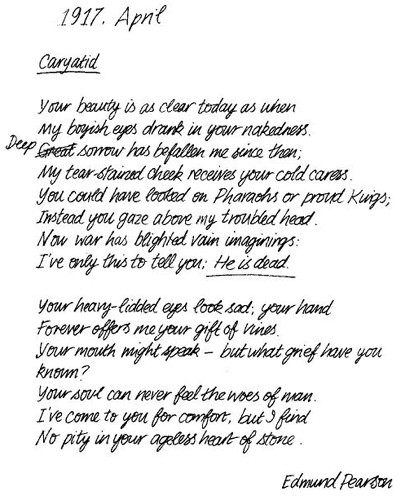

with which he signed himself. Among the letters there was a poem, closely-written on a sheet of lined paper, which Alex had copied out and given him last Christmas Eve.

‘I read this in

The Times

last year, before I knew you,’ Alex had told him. ‘I think you will like it.’