The Shell House (26 page)

‘Why good?’

‘It brings everybody inside. And when they’re inside they’ll spend money.’

For the next hour and a half, while it rained steadily, the Coach House was packed. ‘Like the Harrods sale!’ Margaret beamed, pushing her way through to collect the notes from the bottom of the cash-box. ‘Our extra publicity this year has certainly paid off.’ Quite why wet weather should provoke a rush for green tomato chutney Greg had no idea, but he and Faith were fully occupied with taking money, sorting change and replenishing their tables from the boxes underneath until there was little more to be sold. When the rain eased and the visitors began to drift outside or back to their cars, Margaret came to take over the stall. ‘Go and have a wander round. You’ve done well here.’

Outside, under the dripping trees, there was just a straggle of people, some smugly clad in Goretex and boots, others less suitably in shorts and open sandals. Automatically, Greg and Faith made their way across the orchard and down the steps to the lake. The last guided tour was making its way ahead of them, led by Faith’s father. He gathered his group around the grotto, where Greg and Faith caught up; they heard the exclamations of people seeing it for the first time.

‘This is the grotto,’ Mike Tarrant informed them. ‘One of the last features to be added to the grounds, in the late nineteenth century. Henry Pearson—the owner of Graveney at the time—had it made in memory of his baby son, Edmund, who died in infancy. We think he did the tile decorations himself. It’s not obvious at first, but when you look you can see EP, for Edmund Pearson, again and again in the pattern—here, and here. His surviving son, of course, was the next Henry, the last owner, who lived here until the fire in 1917. Sadly, he had no heir—his only son died in the First World War . . .’

The old lie, Greg thought. People said that so often that they believed it.

The people stared and touched and exclaimed, some of them taking photographs, some gazing blankly, chewing gum. Mike Tarrant looked up at the darkening sky. ‘I think we’d better hurry if we don’t want to get drenched again. We’ll just do a quick walk round the lake, then up to the sunken garden . . .’

As soon as the crocodile moved on, Faith darted inside the grotto and sat on the marble bench, reclaiming it for her own.

‘I keep forgetting about that other Edmund Pearson—the first one.’ Gently she touched the tile pattern. ‘How weird if our Edmund really did drown himself here. I bet he came in here first, don’t you? And saw his own ready-made memorial. Perhaps that’s what gave him the idea.’

‘No grave, but a grotto. It’s better than most people get, isn’t it?’ Greg stood looking out at the ruffled water.

‘We’d have to drag the lake—that’s the only way we could ever prove anything.’

Greg shook his head. ‘No. Let him stay.’

‘I wasn’t

serious

!’

The line of visitors had reached the farthest end; one of them, a boy, skimmed a flat stone that pinged across the surface. Then a fresh spatter of rain sent them all scurrying up the log path into the shelter of trees. The water was steely-grey, pitted with raindrops. Greg retreated into the grotto and stood looking as the last straggler disappeared, and the lake and its trees became theirs again. There was something very peculiar about the light, dull but intense, as if gathering itself; about to remark on this, Greg saw that the rain had stopped as suddenly as it had begun, and the lake was lit almost theatrically by vivid sunlight. Half a rainbow appeared in the retreating rain; from where they stood it looked as if it touched the ground precisely where the shell of the Hall was hidden from sight by the rise of ground. Greg stood looking at the eerie, beautiful light, wishing he had his camera. The trees opposite looked spotlit, every leaf and stalk and branch clear. And the rainbow—according to the Bible, hadn’t God used that as a promise, after the Flood, setting his seal in the sky? It was the nearest thing to kneeling oxen Faith was likely to get.

‘Can you see the rainbow’s end?’ he said.

‘Nearly. But is the rainbow really there? Or do we only think we’re seeing it?’

‘It’s an illusion, and we’re both seeing it, but we’re not seeing exactly the same because of the distance between us. I’d have to see through your eyes to see exactly the same rainbow you’re seeing.’

‘Are you saying more than you’re saying?’

‘I’m not sure. I’m a Physics student and I know that what we’re seeing is sunlight refracted by moisture in the air. But can you believe that’s

all

it is?’

‘What, then?’ Faith said. ‘You’ll be telling me next you think there’s a pot of gold buried at the end.’

‘Did you know that it wasn’t till Isaac Newton that we understood about rainbows—about how light gets dispersed into different colours? And then he was criticized for spoiling the mystery of it.’

Faith nodded. ‘Understanding isn’t the same as wondering. It’s fading—look. Going, going . . . gone.’

‘There’s still a bit left, if you want it,’ Greg said, looking towards the trees. ‘Anyway, I don’t believe that. When you understand something you get something else to wonder at. We know now what makes a rainbow, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth looking at. Looking properly. And we ought to think

Wow!

and say thank you, because the world is arranged the way it is.’

I sound like Jordan, he realized; that’s a Jordan thought. For the first time he understood the meaning of the word

gutted

. He felt a physical pain deep inside, as if his intestines were being slowly pulled out, leaving him hollow.

‘But the world has evil things in it as well, not just sunshine and rainbows. You gave that as a reason not to believe. And anyway,’ Faith said, ‘who should I thank?’

‘Who do you think you should thank?’

‘You want me to say that God’s put this show on just for me? And therefore I have to believe in Him again?

Except you see signs and wonders, you will not

believe

. That’s what Jesus said to the man at Capernaum whose son He had healed.’

‘OK, so that means you might not get signs and wonders—it doesn’t tell you to take no notice when you

do

get them. Jesus performed miracles, didn’t he?’

‘Yes, for healing! Not conjuring tricks.’

‘OK then. Dean’s going to take up his bed and walk, and we’ve just seen a rainbow. What more do you want—loaves and fishes?’

‘You’re making it too simple,’ Faith objected.

‘And you’re making it too complicated.’

‘But if I believe, then you have to believe as well,’ Faith said, ‘because of your bargain. I have to drag you with me. And you don’t want that.’

‘But I do want

you

to believe,’ Greg said, with certainty.

‘Why?’

‘I want to know it’s possible.’

‘You want me to save you the effort of believing for yourself? Sorry, I can’t decide to believe because you want me to. And you can’t decide to believe because of a bet.’

‘No, but I can be a—a wondering agnostic.’

‘There’s nothing stopping you from being that. It doesn’t depend on whether I believe or not.’

‘OK, then.’ Greg moved nearer to the shore and felt in his jeans pocket for Faith’s crucifix. He leaned out over the water, dangling it. ‘A rainbow’s just particles arranging themselves in a certain way. Dean’s getting better because he was going to get better anyway. So neither of us believes. Either there is a God behind everything or there isn’t—there’s no half-way, a God who’s only partly there, or a God who can’t make up his mind whether he exists or not. And we’ve both decided he doesn’t. In which case you won’t be needing this tacky piece of jewellery. There’s no point hanging on to it, is there?’

‘Wait—’

‘Let’s donate it to Edmund.’

God doesn’t make bargains, he thought, but I can make one with myself. If Faith gets her faith back, I tell the truth—to myself, to everyone who matters. And if she doesn’t, I don’t have to. Simple.

He glanced at Faith. Intensity sharpened his actions as he whirled the chain around like a lasso, preparing. Faith watched him uneasily. Taking an exaggerated breath, he swung his arm back, watching her from the corner of his eye. Like an Olympic discus-thrower, he balanced himself for the throw.

‘No!’

Faith grabbed his arm at the moment of lunging. The crucifix whirled over the water, catching the light.

See the next page for a preview of

Linda Newbery’s evocative novel

Sisterland

Available in hardcover from

David Fickling Books

Excerpt from

Sisterland

copyright © 2004

by Linda Newbery. All rights reserved.

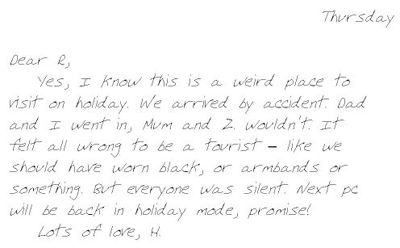

Only a Visitor

They came across Natzwiller-Struthof by chance. Not at all sure that she wanted to go in, Hilly knew she would, as the road had brought her to the gates. It wasn’t the sort of opportunity you could miss.

With their baguettes and Camembert and other picnic items stowed in the boot, they had been looking for a place to stop for lunch. It was another hot day, too relentlessly hot for walking round villages or for visiting Strasbourg. The forest offered coolness and shade, trickling streams and grassy clearings. Hilly, in the front passenger seat with the road atlas on her lap, had noticed the roadside signs with the three crosses indicating some sort of war memorial.

‘Natzwiller-Struthof?’ her father said, changing to a lower gear for a sharp uphill bend. ‘It’s a concentration camp. Was. Open to visitors now, I think.’

‘In

France

?’ said Zoë, in the back seat.

‘Zoë, this part of France was taken over by Germany at the start of the war.’ Her father glanced back. ‘You know, the Occupation of the Rhineland! We were talking about that yesterday, remember?’

Zoë lifted her chin and stared out of the side window, haughty and withdrawn.

Hilly said, ‘I know, though—it does feel a bit peculiar, doesn’t it? Here in the hills—the signs pointing up and up. It’s like we’re not in any particular country—as if the mountains are a sort of barricade between the Rhine and the rest of France.’

‘Barricade against British tourists, as well,’ her father said. ‘Anyone noticed how few Brit number plates there are? Dutch, German, but very few GBs—I’ve only seen one or two since we got here. Looks like Alsace is a well-kept secret.’

‘No beaches, that’s why,’ said Rose, the girls’ mother. ‘Lots of people want beaches.’

‘So why do we have to be different?’ Zoë said, still huffy. She hadn’t wanted to come on this holiday, and was making sure everyone knew. She complained about the room she was sharing with Hilly; she complained that self-catering meant they were forever shopping for food; she complained that it was too hot.

‘

I

wish you’d stayed at home, too!’ Hilly had told her earlier, in a fierce, muttered conversation in their bedroom, before their parents were awake. ‘It’s Dad’s birthday today, so you might make a slight effort.’

How many more times would they go on holiday like this, all four of them? Hilly wondered. This was possibly the last time. For their parents, this Alsace trip was revisiting the past; they’d come here nineteen years ago, the summer they got married. Although she had seen photographs, Hilly was surprised by the wooded slopes of the Vosges mountains, the deep valleys, the almost ridiculously picturesque villages along the wine-growing route. It was as she imagined the Swiss Alps: high meadows rich in wild flowers, remote farmsteads with logs stacked under the house eaves.

As they followed the memorial signs the road narrowed between stands of spruce, the young trees clustering so thickly that the farther slopes looked furred in green. Through the open window Hilly smelled warm grass and the resinous tang of pine; she saw verges bright with the purply mauves of wild thyme and harebells. It seemed an unlikely journey to a concentration camp, she thought, remembering documentaries she’d seen at school: bleak industrial areas, windswept flatlands, and those terrible railway tracks that led one way.

A sign to the left took them to a levelled parking area. The Craigs’ car nosed into line next to a Peugeot with a French number plate, facing trees and a grassy slope. The large car park was two-thirds full; there was a blockish building that looked like toilets, and a sign asking visitors not to picnic or play ball games. Looking towards the entrance, Hilly saw iron gates, a high wire fence.

‘You must be joking,’ said Zoë from the back seat. ‘You’re not seriously expecting us to go in?’

‘You can wait here if you like,’ their father told her. ‘I’d like to see inside. Anyone coming?’

‘Me,’ said Hilly.

‘You would.’ Zoë was sliding out of the car, trailing the lead of her Walkman. ‘Just up your street, isn’t it?—holiday combined with doom and gloom. Why be happy when you can be miserable?’

‘You’d know all about that!’ Hilly stood up, stretching. ‘Coming, Mum?’

Rose glanced towards the gates. ‘You go with Dad. Don’t think I will. I’ll wait with Zoë.’

Zoë reached for her magazine, slammed the car door and moved into the shade of a silver birch, settling herself on the grass. ‘I hope you’re not going to take ages—I’m starving! Can’t we start on the lunch, Rose?’

Zoë had recently taken to calling her mother by her first name; although Rose didn’t mind, Hilly couldn’t do it without feeling self-conscious. She noticed, too, that Zoë always called their father Dad, even Daddy: never Gavin.

‘We can’t picnic here.’ Rose nodded in the direction of the sign that urged Silence and Respect.

‘No one’s going to tell us off, are they?’

‘We’ll wait for Dad and Hilly,’ Rose said firmly. Zoë sighed, rolled over onto her front and flicked open her magazine with the martyred air she was so practised at conveying; Hilly gave her a disparaging glance, which went unnoticed.

‘Get a shift on, then, if you’re going,’ Zoë said, while Hilly hesitated about whether or not to take her camera. ‘Great choice for your birthday outing, Dad.’

‘Take as long as you like.’ Their mother was delving in the glove compartment for her paperback. ‘There’s no rush. We’ll be fine here, reading in the shade.’

Walking towards the ticket office, Hilly had the sense of stepping out of the sunshine and into cold shadow. Her father nudged her and nodded towards a sign in French: Entry free to children under sixteen. ‘That’d put Zoë in an even worse mood,’ he remarked, sorting Euros, ‘being classed as a child. Deux adultes, s’il vous plaît.’ The woman in the booth glanced behind him to see where the other adult was, before realizing he meant Hilly; quickly she covered up her mistake. ‘Voilà.’ She handed them their tickets. ‘

Bonne journée

.’

They passed through gates into a large wire enclosure, surrounded by a high double fence with watchtowers at intervals on the perimeter. It was incongruous, high on the hillside: rather like coming across a floodlit football pitch in the middle of a forest. The area inside, on a downhill slope, was terraced steeply; there was one barrack-style building at the top, with a sign saying MUSÉE, and two others at the lower end. Hilly felt a constriction of fear at her throat, and her heart beating. But I can walk out again, she thought, whenever I want to. She felt all wrong, dressed for the heat in cut-off jeans, a purple T-shirt and wide-brimmed hat; but everyone else was similarly clad. She saw crop-tops, painted toenails, sun-dresses; men in shorts, with hairy legs. We might be on a beach, she thought, or visiting a theme park. But this was real. And in spite of their holiday clothes, people were subdued, speaking to each other only in whispers. Seeing a woman in front remove her straw hat as she entered the museum, Hilly did the same.

TU N’ES QUE VISITEUR DU PALAIS DE LA MORT, she read on a framed card inside: YOU ARE ONLY A VISITOR IN THE PALACE OF DEATH.