The Shipping News (16 page)

17

The Shipping News

“Ship’s Cousin, a favored person aboard ship …”

THE MARINER’S DICTIONARY

PHOTOGRAPHS

of the Botterjacht on his desk. Dark, but good enough to print, good enough to show the vessel’s menacing strength. Quoyle propped one up in front of him and rolled a sheet of paper into the typewriter. He had it now.

KILLER YACHT AT KILLICK-CLAW

A powerful craft built fifty years ago for Hitler arrived in Killick-Claw harbor this week. Hitler never set foot on the luxury Botterjacht,

Tough Baby

, but something of his evil power seems built into the yacht. The current owners, Silver and Bayonet Melville of Long Island, described the vessel’s recent rampage among the pleasure boats and exclusive beach cottages of White Crow [142] Harbor, Maine during Hurricane Bob. “She smashed seventeen boats to matchsticks, pounded twelve beach houses and docks into absolute rubble,” said Melville.

The words fell out as fast as he could type. He had a sense of writing well. The Melvilles’ pride in the boat’s destructiveness shone out of the piece. He dropped the finished story on Tert Card’s desk at eleven. Card counting waves, fidgeting through wishes.

“This goes with the shipping news. Profile of a vessel in port.”

“Jack didn’t say anything to me about a profile. He tell you to do it?” His private parts showed in his polyester trousers.

“It’s extra. It’s a pretty interesting boat.”

“Run it, Tert.” Billy Pretty in the corner rapping out the gossip column.

“What about the

ATV

accident? Where’s that?”

“That’s the one I didn’t do,” said Quoyle. “Wasn’t much of an accident. Mrs. Diddolote sprained her wrist. Period.”

Tert Card stared. “You didn’t do the one Jack wanted you to do and you did one he don’t know you did. Hell, of course we’ll just run it. Proper thing. I haven’t seen Jack in a flaming fit for a long time. Not since his fishing boot fell onto the hot plate and roasted. Tell you what, you better leave your motor running when you come in tomorrow morning.”

What have I done, thought Quoyle.

“Don’t get your water hot about Edith Diddolote. She’s in Scruncheons with her sprained wrist and her fiery remarks.” Billy’s diamond pattern gansey unraveling at the cuffs. The blue eyes still startled.

¯

“Bloody hell, about time you got here. Billy’s up at the clinic getting his prostate checked and Jack’s on his way down. He wants to see you.” Tert Card snapped open a fresh copy of the

Gammy Bird

. Shot black looks from his gledgy eyes. At his desk, Nutbeem lit his pipe. The smoke came up in white balls. Outside the window fog and a racing wind that could not carry it away.

“Why?” said Quoyle apprehensively. “Because of the piece?”

[143] “Yep. He probaby intends to tear your guts out for that Hitler yacht piece,” said Tert Card. “He don’t like surprises. You should have stuck to what he told you to do.”

The roar of the truck engine, the door slam; Quoyle went sweaty and tense. It’s only Jack Buggit, he thought. Only terrible Jack Buggit with his bloody knout and hot irons. Reporter Bludgeoned. His sleeve caught on the bin of notes and papers on his desk; paper sprayed over the desk. Nutbeem’s pipe twisted in his teeth, tipped out a nugget of burning dottle as he unkinked the telephone cord by letting the receiver hang low and spin. Looked away.

Jack Buggit strode in, ginger eyes jumped around the room, stopped on Quoyle. He hooked his hand swiftly over his head as though catching a fly and disappeared behind the glass partition. Quoyle followed.

“All right, then,” said Buggit, “This is what it is. This little piece you’ve wrote and hung off the end of the shipping news—”

“I thought it’d perk the shipping news up a little, Mr. Buggit,” said Quoyle. “An unusual boat in the harbor and—”

“ ‘Jack,’ ” said Buggit.

“I don’t have to write another one. I just thought—.” Reporter Licks Editor’s Boot.

“You sound like you’re fishing with a holed net, shy most of your shingles standin’ there hemming and hawing away.” Glared at Quoyle who slouched and put his hand over his chin.

“Got four phone calls last night about that Hitler boat. People enjoyed it. Mrs. Buggit liked it. I went down to take a look at it meself and there was a good crowd on the dock, all lookin’ her over. Course you don’t know nothin’ about boats, but that’s entertaining, too. So go ahead with it. That’s the kind of stuff I want. From now on I want you to write a column, see? The Shipping News. Column about a boat in the harbor. See? Story about a boat every week. They’ll take to it. Not just Killick-Claw. Up and down the coast. A column. Find a boat and write about it. Don’t matter if it’s a long-liner or cruise ship. That’s all. We’ll order your computer. Tell Tert Card I want to see him.”

But no need to say anything to Tert Card who heard everything [144] over the partition. Quoyle went back to his desk. He felt light and hot. Nutbeem clasped both hands over his head and shook them. His pipe twisted. Quoyle rolled paper into the typewriter but didn’t type anything. Thirty-six years old and this was the first time anybody ever said he’d done it right.

Fog against the window like milk.

18

Lobster Pie

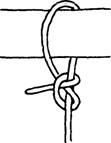

“The lobster buoy hitch ... was particularly good

to tie to timber.”

THE ASHLEY BOOK OF KNOTS

THE BOY

in the backseat had plenty to say in wide, skidding vowels that only his mother understood. Quoyle got the sense, though; adventures ran through Herry’s talk, a kind of heady exultation in such things as a blue thread on his sweater cuff, the drum of ocherous rain into puddles, a cookie in a twist of tissue. Anything bright. The orange fishermen’s gloves. He had a wild sense of color.

“Gove! Gove!”

Or the blue iris in Mrs. Buggit’s garden.

“Vars!”

“Nothing wrong with his eyesight,” said Quoyle.

Here was a sudden subject for Wavey. Down’s syndrome, she said, and she wanted the boy to have a decent life. Not his fault. [146] Not to be stuffed away in some back room or left to cast and drool about the streets like in the old days. Things could be done. There were other children along the coast. She had asked about other children, found them, visited the parents—her brother Ken took her in his truck. Explained things could be done. “These children can learn, can be taught,” she said.

Fervent. A ringing voice. Here was Wavey on fire. Had requested books on the condition through the regional library. Started the parents’ group. Specialists from St. John’s up to speak. Tell what could be done. Challenged children. Got up a petition, called meetings, ah, she said, they wrote letters asking for the special education class. And got it. A three-year-old girl in No Name Cove had never learned to walk. But could learn, did learn. Rescuing lost children, showing them ways to grasp life. She squeezed her hands together, showing him that anyone alive could clench possibilities.

What else, he thought, could kindle this heat.

She asked Quoyle for a ride to the library. Friday and Tuesday afternoons the only time it was open. “See, Ken takes me when he can, but he’s fishing now. And I miss my books. I’m the reader. And I read to Herry, just read and read to him. And get for Dad. What he likes. Mountain climbing, hard travels, going down to the Labrador.”

Quoyle got ready Friday morning, put on his good shirt. Cleaned his shoes. Didn’t want to be excited. For God’s sake, giving someone a ride to the library. But he was.

¯

The library was a renovated old house. Square rooms, the wallpaper painted over in strong pistachio, melon. Homemade shelves around the walls, painted tables.

“There’s a children’s room,” said Wavey. “Your girls might like to have a few books. Sunshine and Bunny.” She said their names tentatively. Her hair combed and plaited; a grey dress with a lace collar. Herry already at the bookshelves, pulling at spines, opening covers into flying fancies.

Quoyle felt fourteen feet wide, a clumsy poisoned pig, and [147] every way he turned his sweater caught on some projecting book. He tumbled humorous essayists, murderers, riders of the purple sage, sermonizing doctors, caught them in midair or not at all. Stupid Quoyle, blushing, in a tiny library on a northern coast. But got into the travel section and found the Erics Newby and Hansen, found Redmond O’Hanlon and Wilfrid Thesiger. Got an armful.

They went back by way of Beety’s kitchen to get his girls. Who didn’t know Wavey.

A ceremonious introduction. “And that’s Herry Prowse. And this is Wavey. Herry’s mother.” Wavey turned around and shook their hands. And Herry shook everyone’s hand, Quoyle’s, his mother’s, both hands at once. His fingers, palms, as hot as a dog’s paws.

“How do you do,” said Wavey. “Oh how do you do, my dears?”

Pulled up in front of Wavey’s house to the promise of tea and cakes. Sunshine and Bunny fighting in the station wagon to see the yard next door, menagerie of painted dogs and roosters, silver geese and spotted cats, a wooden man in checked trousers grasping the hand of a wooden woman. A wind vane that was a yellow dory.

Then Bunny eyed the plywood dog with its bottle-cap collar. Mouth open, fangs within the lips, the nose sniffing the wind.

“Dad.” She gripped Quoyle’s collar. “There’s a white dog.” Whimpered. Quoyle heard her suck in her breath. “A white dog.” And caught the subtle tone, the repetition of the awful words, “white dog.” Then he guessed something. Bunny was inducing a thrill—working herself up. Girl Fears White Dog, Relatives Marvelously Upset.

“Bunny, it’s only a wooden dog. It’s wood and paint, not real.” But she didn’t want to let go of it. Rattled her teeth and whined.

“I guess we’ll come for tea another time,” said Quoyle to Wavey. And to Bunny he gave a stem look. Nearly angry.

“Daddy,” said Sunshine, “where’s their father? Herry and Wavey?”

¯

On the weekend Quoyle and the aunt patched and painted. Dennis started the studding in the kitchen. Sawdust on everything, [148] boards, two-by-fours stacked on the floor. The aunt scraping another cupboard to bare wood.

Quoyle chopped at his secret path to the shore. Read his books. Played with his daughters. Saw briefly, once, Petal’s vanished face in Sunshine’s look. Pain he thought blunted erupted hot. As though the woman herself had suddenly appeared and disappeared. Of course she had, in a genetic way. He called Sunshine to him, wanted to take her up and press his face against her neck to prolong the quick illusion, but did not. Shook her hand instead, said “How do you do, and how do you do, and how do you do again?” Invoking Wavey, that tall woman. Made himself laugh with the child.

¯

One Saturday morning Quoyle went in his boat down to No Name Cove for lobsters. Left Bunny raging on the pier.

“I want to come!”

“I’ll give you a ride when I come back.”

Put up with the No Name witticisms over his boat. It was an infamous craft that they said would drown him one time. On the way back he skirted a small iceberg drifting down the bay. Curious about the thing, a lean piece of ice riddled with arches and caves. But as big as a bingo hall.

“More than four hundred icebergs have grounded this year so far,” he told the aunt. He couldn’t get over them. Had never dreamed icebergs would be in his life. “I don’t know where they went ashore, but that’s what they say. There was a bulletin on it yesterday.”

“Did you get the lobsters?”

“Got them from Lud Young. He kept shoving extras in the basket like they were lifesavers. Tried to pay for them but he wouldn’t take it.”

“Season will be over pretty soon, we might as well eat ‘em while we can get ‘em. If he wants to give lobster to you, take them. I remember the Youngs from the old days. Hair hanging down in their eyes. You know, the thing that’s best,” said the aunt, “is the fish here. Wait until the snow crab comes in. Sweetest meat in the world. Now, how do we want to do these lobsters?”

[149] “Boiled.”

“Yes, well. We haven’t had a nice lobster chowder for a while. And there’s advantages to that.” She looked toward the other room where Bunny was hammering. “We won’t have to hear that screeching about ‘red spiders’ and fix her a bowl of cereal. Or I could boil them and pull out all the meat and make lobster rolls. Or how about crêpes rolled up with the meat in a cream sauce inside?”

Quoyle’s mouth was watering. It was the aunt’s old trick, to reel out the names of succulent dishes, then retreat to the simplest dish. Not Partridge’s style.

“Lobster salad is nice, too, but maybe a little light for supper. You know, there’s a way Warren and I used to have it at The Fair Weather Inn on Long Island. The tail meat soaked in saki then cooked with bamboo shoots and water chestnuts and piled into the shells and baked. There was a hot sauce that was out of this world. I can’t get any of those things here. Of course, if we had some shrimp and crabmeat and scallops I could make stuffed lobster tails—same idea, but with white wine and Parmesan cheese. If I could get white wine and Parmesan.”

“I bought cheese. Not Parmesan. It’s just cheese. Cheddar.”

“Well that settles it. Lobster pie. We don’t have any cream, but I can use milk. Bunny will eat it without roaring and it’ll be a change from boiled. I want to make something a little special. I asked Dawn to come over to supper. I told her six, so there’s plenty of time.”

“Who?”

“You heard me. I asked Dawn to come over. Dawn Budget. She’s a nice girl. Do you good to talk to her.” For the nephew did nothing but work and dote.

There was a prodigious pounding from the living room.

“Bunny,” called Quoyle. “What are you making? Another box?”

“I am making a

TENT

.” Fury in the voice.

“A wooden tent?”

“Yeah. But the door is crooked.” A crash.

“Did you throw something?”

[150] “The door is

CROOKED

! And you said you would give me a ride in the boat. And didn’t!”

Quoyle got up.

“I forgot. O.k., both of you get your jackets on and let’s go.” But just outside the door Bunny invented a new game while Quoyle waited.

“Lie down on your back, see, like this.”

Sunshine thumped down on her back, stretched out her arms and legs.

“Now look up near the top of the house. And keep looking. It’s scary, it’s the scary house falling down.”

And their gazes traveled up the clapboards, warped crooked with storms, to the black eaves. Above the peak of the house the thin sky and clouds raced diagonally. The illusion swelled that the clouds were fixed and it was the house that toppled forward inexorably. The looming wall tipped at Sunshine who scrambled up and ran, deliciously frightened. Bunny stood it longer until she, too, had to get up and tear away to safe ground.

Quoyle made them sit side by side in the boat. They gripped the gunwales. The boat buzzed over the water. “Go fast, Dad,” yelled Sunshine. But Bunny looked at the foaming bow wave. There, in the snarl of froth, was a dog’s white face, glistering eyes and bubbled mouth. The wave surged and the dog rose with it; Bunny gripped the seat and howled. Quoyle threw the motor into neutral.

The boat wallowed in the water, no headway, slap of waves. “I saw a dog in the water,” sobbed Bunny.

“There is

no

dog in the water,” said Quoyle. “Just air bubbles and foam and a little girl’s imagination. You

know

Bunny, that there cannot be a dog that lives in the water.”

“Dennis says there’s water dogs,” sobbed Bunny.

“He means another kind of dog. A real live dog, like Warren”—no, Warren was dead—“a live dog who can swim, who swims in the water and brings dead ducks to hunters.” Christ, was everything dead?

“Well, it looked like a dog. The white dog, Dad. He’s mad at me. He wants to bite me. And make my blood drip out.” The tears coming now.

[151] “It’s not a true dog, Bunny. It’s an imaginary dog and even if it looks real it can’t hurt you. If you see it again you have to say to yourself, ‘Is this a real dog or is this an imaginary dog?’ Then you’ll know it isn’t real, and you’ll laugh about it.”

“But Dad, suppose it

is

real!”

“In the water, Bunny? In a stone? In a piece of plywood? Give me a break.” So Quoyle tried to vanquish the white dog with logic. And headed back to the dock very slowly so there was no bow wave. Getting fed up with the white dog.

¯

In the afternoon Quoyle set the table while the aunt squeezed and folded piecrust.

“Put on the red tablecloth, nephew. It’s in the drawer under the stairs. You might want to change your shirt.” The aunt stuck two white candles in glass holders although it was still full sunlight outside. The sun would not set until nine.

Bunny and Sunshine were tricked out in white tights, their velvet Thanksgiving dresses with lace collars. Sunshine could wear Bunny’s patent leather Mary Janes, but Bunny sulked in grimy sneakers. And her dress was too small, tight under the arms and short. Hot, as well.

“Here she comes,” said the aunt, hearing Dawn’s Japanese car curving toward the house. “You girls mind your manners, now.”

Dawn came up the steps, balancing in white spike heels big enough to fit a man, smiling with brown lips. Her nylon blouse glowed; the hem of the skirt hung low behind. She carried a bottle. Quoyle thought it was wine but it was white grape juice. He could see the Sobey’s price tag. The toes of her shoes jutted up at a painful angle.

He thought of Petal in her dress with the fringe, the long legs diving down to slippers embroidered with silver bugles, Petal, darting around in a cloud of Trésor, shooting glances at her reflection in mirror, toaster, glass, flicking her fingers at Quoyle’s openmouth desire. He felt a pang for this poor moth.

The conversation dragged, Dawn saying the bare floors and hard windows were “striking.” Sunshine heaped grimy bears and [152] metal cars in her lap, it’s a bear, it’s a car, as though the visitor came from a country where there were no toys.

At last the aunt thumped the fragrant pastry in front of Quoyle. “Go ahead and dish it up, Nephew.”

She lit the candles, the flames invisible in the cylinder of sunlight that fell across the table, but the smell of wax reminding them, brought the dish of peas and pearl onions, the salad.