The Shirt On His Back (35 page)

Read The Shirt On His Back Online

Authors: Barbara Hambly

27

The Omaha Dark

Antlers and two Crow warriors came into the tipi a few minutes later, to fetch

Veinte-y-Cinco. The woman rose, kissed Hannibal and Shaw ('Don't I get one for

luck?' inquired Goodpastor, and with a quick flicker of a grin she gave him one

that would have been grounds for divorce in most states of the Union), and

slipped out into the night.

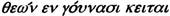

'

'

quoted

January softly. 'Now it lies upon the knees of the gods.'

Hannibal sighed.

'And we all know how trustworthy

they

are.'

Shortly after

that, a couple of Crow women came in with food - chunks of roasted

mountain-sheep, and a tin kettle of stew - and with them, Goodpastor's engages,

two young border-ruffians named Laurent and Tonio. They brought the news that

the remaining Omaha warriors were setting up lodges of dead wood and sagebrush

for the night, as if in a war camp, just beyond the tipis of the Crow, and that

the Crow were keeping guard on them. 'That Mexican trader was with them,' added

Tonio, the younger of the two - brothers, January guessed, by their looks, and

by the way Tonio kept close to the elder as if for protection.

'As a guest,

would you say?' Goodpastor poured out water from the skin hanging from one of

the tent poles, into the pewter cup that the young men shared. 'Or a prisoner?'

'A guest, looked

like. He sits with Iron Heart at his fire.'

'Well,' sighed

Goodpastor, 'consarn.'

'And are

you

a guest here,

sir?' inquired January as the two boys settled down with bowls of wild mutton

and stew. 'Or a prisoner?'

'And

did

you drop out of

the sky?' added Hannibal.

'Wish I had,'

retorted the Indian Agent. 'I am entirely too old for that ride up the Platte

in a wagon-train. No, I set out

from Fort Laramie like a respectable representative of the

United States Congress, with ten engages, a secretary and a half-breed guide

who couldn't find his way back from the outhouse. When we got to the Popo Agie

we heard from a couple of Shoshone hunters that there was a band of Crow -

eighty lodges - skulking around the mountains near the rendezvous without

comin' into it, which sounded downright fishy to me. I had the boys make camp,

took those two scoundrels with me, did some scouting on my own and here I am.'

'Here you are,'

agreed January. 'But could you leave if you wanted to?'

'I could, yes.

Or at least I think I'll be able to, once Walks Before has figured out what he

wants to do with you and with Iron Heart. I'm on his territory. I'm no more

than an envoy from the Congress to the Crow. And I wouldn't care to bet on it

that he'd let me leave the camp tonight - or that Iron Heart's boys wouldn't

find a way of making sure I didn't get to the rendezvous if I

did

leave, sort of

quiet like in the woods. We're a long ways from anywhere, here, and if they

plan on killin' any white men they're not going to leave an Indian Agent to go

tellin' the tale.'

'Ah,' said

January. 'Then all we've done is make your position here worse.'

'Hell, I been in

worse places. Though things could get damn sticky if that woman tries to make a

break when she gets near the rendezvous, and there's an attack made on this

camp. I ain't sayin' Titus wouldn't keep a lid on it if he could—'

'Titus?'

'That sourpuss

Controller the AFC's got with their factory there this year. He's the one paid

Walks Before thirty rifles and three barrels of gunpowder to come down here and

not let a soul see 'em. There's talk all over this camp of them attackin' the

smaller trains as they leave the rendezvous - an' of stagin' an attack on the

AFC train, for show, so word can be took back to Congress that it was the

Hudson's Bay Flatheads, an' that the military's needed to keep them pesky

British an' their Indian allies in line, just like back in 1812. I been workin'

on convincin' Walks Before that it ain't such a good plan.'

He pitched a

clean-picked sheep-rib into the fire, wiped his fingers on his bandanna.

'Another reason I'm not tryin' to leave this camp just yet. So I would

appreciate it,' he went on, 'if you boys would give me some idea of what's been

happenin' at the rendezvous.'

The white-haired

Indian Agent listened with interest to January's account of the trade in liquor

with the Indians ('Lord, Bill Grey made it sound like Sodom and Gomorrah,') and

the attempted scalping on the way back from the banquet ('That sounds like

Titus, all right . . .'). He grinned at the effort to convince Congress that

the dead man was himself, but his eyes narrowed sharply when January spoke of

Bodenschatz's plan to give away poisoned liquor.

'That's no

Indian plan,' he rumbled, and he stroked the milk- white stubble of his trail

beard. 'Mission Indians, maybe - that have learned how civilized folks go about

their business.'

'My brother

stumbled on a half-wrote letter from Bodenschatz to Iron Heart.' Shaw spoke up

from his side of the fire. 'I thought, myself, it mighta had somethin' to do

with the AFC tryin' to push Congress into sendin' troops to take Oregon

...

an' like the

young fool he was, I think Johnny just up an' asked Bodenschatz about it, an'

he was found dead not long later. Only when the Beauty up an' died, after

drinkin' the last of the liquor they'd found in the old man's coat, did we

start to put together that there was different game afoot. Worse game.'

'You still have

those letters from Boden to his father?'

'They were in my

hand when the Omahas attacked us on the quarantine island,' said Hannibal.

'Even had I had the chance to get my hand to my coat before running for our

lives, they wouldn't have survived the river. And if they

had

survived, I'd

have eaten them the following day.'

'An' you had no

idea Frank Boden - or Franz Bodenschatz - would be posin' as a Mexican trader

here?'

'We knew he'd be

here,' said January. 'The only man who could have recognized him for sure - er

- died the first day we were in camp . . .'

'And I'm not

entirely certain,' added Hannibal, 'that I'd recognize Jim Bridger or Robbie

Prideaux, if you scrubbed and clipped them. For that matter, Mr Goodpastor -

and I hope you'll forgive my making the inevitable inferences - it sounds as if

there are men at the rendezvous who should have known the body we found wasn't

you.'

'Make all the

inevitable inferences you please.' Goodpastor plucked another rib from the

fire, tore the meat from it with strong white teeth. 'They'd have known quick

enough the old man you found wasn't Medicine Lynx - which was the name I went

by when I was living with the Mandans in '09. When I was trapping down around

Taos later on, I still went by El Lince. Carson and Bridger and a dozen of

those boys

would

have

known me, if they'd seen me face to face. I only started using my right name

again when I went back to Missouri and met Mrs Goodpastor - Miss Milliken that

was - and got into politics. But Grey sure as hell knows me. How bad was the

old man tore up when he was found?'

'Bad enough,'

said January, and Manitou - silent on the other side of the fire - looked away.

'But obviously

Bodenschatz knew

you

.'

Hannibal turned to the trapper.

'I'm hard to

miss.'

Particularly,

reflected January, surveying that bear-like hulk, if a man of such massive size

had a reputation for ungovernable, murderous rage. Once Franz Bodenschatz had

reached the frontier, rumor of his quarry would not have been hard to find.

Manitou frowned

into the fire. 'And he'd seen me in the court. 1 musta seen him when he spoke

to the judges against me, but them weeks gets confused in my mind. An' he was

bearded at Fort Ivy. Nobody ever called him nuthin' but Frank in my hearin' -

an' now I think on it, I'm not sure I ever saw him in full daylight.'

His heavy

eyebrows drew down, trying to call back recollections of chance meetings,

years ago, in that dark little store. 'Give me a hell of a turn, to see old

Herr Bodenschatz's face in the lantern light. Near to cost me my life, too, for

I slacked my grip on him and he got his second pistol out. I figured he'd come

up with Franz, but it wasn't 'til you told me, Frank at Fort Ivy's name was

Boden, that I knew how they'd found me.'

Outside, the

camp had grown quiet. Somewhere, a woman sang to her children; elsewhere, a dog

barked, the irritable yip of confrontation with some insignificant beast.

January wondered if he'd be able to call all of this back to mind, to write it

down for Rose - smiled at the thought of her envious lamentations:

you actually stayed in an Indian encampment. . . !

And thought of

Veinte-y-Cinco, close enough to the rendezvous to deceive herself that she

could escape from her guards, swim the river, find her daughter . . .

And

who could blame her? January closed his eyes:

Mary, Mother of God, watch over her, who is trying to be the

best mother she can be

. . .

Much later in

the night, he was waked from a light sleep by the sound of scuffling and

whispering, close to the wall of the tipi. He thrust up the lower edge of the

lodge skins and in the starlight he saw, a few yards away, Franz Bodenschatz

struggling silently in the grip of two warriors, a knife in his hand. 'Is this

how you treat your brother,' the German whispered furiously, 'who did all he

could to help you avenge your people?'

The Indian - a

young Omaha warrior whom January did not recognize - replied, 'My people are

not avenged, and a man who seeks to do that which will cause the Crow to kill

us all is not my brother. Come back and sleep. If the lies of the white men

trap them tomorrow, the Crow will kill them, and you will be avenged.'

'Their lies will

poison the minds of the Crow, as they have begun to poison

your

mind, Kills

With A Rock. Else you would let me do what I have sought now for ten years to

do. And as for sleeping, there is no sleep, when my goal lies so near to my

hand.'

Not long after

noon on the following day January heard the camp-dogs barking, and he emerged

from the lodge to see everyone hurrying toward the ford. He and his fellow

prisoners followed the Crow to the river's edge, in time to see the five horses

come down to the opposite bank, with the sharp sun dappling them through the

pine boughs as they crossed. With Dark Antlers and the two Crow rode

Veinte-y-Cinco, in her torn and ragged red-and-green finery, and beside her, in

matronly calico and a sunbonnet, Moccasin Woman, with a battered leather

camp-chest lashed to the back of her saddle.

January

whispered a prayer of thanks, and another one requesting that he'd be able to

convince Walks Before - and Iron Heart - that what he suspected was true.

Warriors, women,

children surrounded the five horses, so closely that none of the prisoners

could push their way close,

but over the dark heads of the crowd, January saw Veinte-y-

Cinco's eyes seek him, then Hannibal, then Shaw. He smiled at her and raised

his hand.

Walks Before

Sunrise and his son, the warrior Lost, were sitting on a blanket before the old

shaman's lodge when the little cavalcade approached. He got to his feet, and

the Indians made way for him to approach the horses. In the crowd January

picked out Iron Heart, and Bodenschatz, in the center of the Omaha warriors.

Bodenschatz saw him, and for a moment their eyes met, a look of such hatred and

spite in the other man's that January was taken aback.

I'm

only here as Shaw's henchman

. . .

To Bodenschatz,

he realized, it was all the same.

He who is not

for me is against

me...

He saw the

German's face when Bodenschatz saw the luggage tied on Moccasin Woman's saddle

and felt his own twinge of spite at Bodenschatz's horror. Spite and triumph.

It's

in there

. . .

He suddenly felt

much better.

Walks Before

held out his hands. 'You are Moccasin Woman?'

'I am.' She

kicked her feet free of the stirrups, slid to the ground and shook out her

faded skirts.

'And have you

brought the clothing of the old white man whom you found dead in the woods, two

nights after the new moon?'

'I have.' She

touched the quillwork bag that hung at her side. Her broad, brown face was sad

but peaceful. 'I asked his forgiveness of him, for taking it away, and did what

I could to honor him. Yet I am a poor woman, and even the smallest pieces of

cloth can be turned to good account, in repairing clothing.'

Walks Before

Sunrise turned to January, motioned for him to step forward and speak.

Bridger and

Prideaux, and every trapper to whom January had spoken, had said the same thing

of the peoples of the plains and the mountains: that they valued speech-making

as a form of honor and would follow explanations and tales with avid interest,

the length of them and the shape of them a compliment to the listeners. He took

a deep breath, and turned to Iron Heart.

'When your

warriors surprised Tall Chief and the Beauty, at the place where they were

burying the dead in Dry Grass Coulee, did one of them take the black coat that

lay in that place?' He knew the answer was yes because he'd already seen the

coat on one of the Omaha warriors, a bizarre sartorial effect in combination

with the young man's leggings and breech cloth. Iron Heart signed the warrior

forward, and January motioned for him to turn around before the Crow shaman, to

show the knife hole in the back of the coat.

'And when you

attacked us on the island near the camp,' January went on, 'and killed the

young trapper who was with us, did you also take his clothing?' This question

also was rhetorical. No Indian in creation would pass up a black silk

waistcoat, and in fact he'd seen Boaz Frye's yellow calico shirt on one of the

warriors, and thought he'd glimpsed the black satin vest on someone else . . .

Which indeed proved to be the case.

But the question

was asked in the proper form, and there was a murmur of approval from the

assembled tribe.

'Listen, now.'

He turned again to Walks Before Sunrise and raised his voice to carry, his

gestures taking in all the tribe gathered around, as if he were telling a story

to Olympe's children. 'And I will tell you all that took place beside Horse

Creek, on the night of the rain just after the moon was new.'

'He lies!'

shouted Bodenschatz. 'He is lying to save his own skin, and that of his

murdering friend!'

Iron Heart

glanced sidelong at him, expressionless. 'Let the black white man speak.'

'Is it true what

you told me, Iron Heart,' said January, 'that the old medicine-man, Boden's

father, left the lodges of the Omaha on the day that I fought with Manitou,

with a bottle of poisoned liquor in his pocket? That he sought to poison

Manitou the Spirit Bear in his own camp, because he had decided he did not wish

to kill all the men at the rendezvous?'

'It was because

he saw the child,' replied Iron Heart. 'The little Mexican girl who played

cards at the liquor tent. She was out in the meadows near our camp that day,

looking for feathers in the long grass. The old man said that he accepted that

the women would die, who were harlots and had come here of their own accord to

lie with men for money. But the child was innocent, he said.'

January

reflected that Klaus Bodenschatz had obviously never seen Pia dealing faro, but

let that pass. Across the open ground, he saw Veinte-y-Cinco silently take

Hannibal's hand.

'He and I

quarreled over this,' Iron Heart went on. 'It had been agreed that Boden would

poison the liquor and give it away after the fight, but there was no victory.

Men came back to the camp and told the old man of this, and also that Manitou

had returned in anger to his own camp. When I came back to the tents of my

people, the old man was already gone.'

'And you, Manitou.'

January turned to the trapper, standing huge and silent among the warriors of

the Crow. 'Did you meet the old man in the woods near your camp?'

'I saw the light

of his lantern.' Manitou, also, had learned what the nations of the plains

considered the honorable way of speaking. 'I had not known the man Boden in the

camp, but his father I knew. The old man was the father of a woman that I

loved, a woman I killed in a fit of madness, many years ago. He fired a pistol

at me from hiding. I had my rifle, but I did not want to kill him. He had a

second pistol, and in the struggle to get it from him I hurt him - broke his

ribs, and broke his leg. I was angry already from fighting Winter Moon -' he

nodded toward January - 'and I could see the fire of my madness beginning to

flicker at the sides of my eyes. Still I remained long enough to tie up the old

man's wounds. I tore up the shirt he wore, to brace his ribs and to bandage my

own arm where his first bullet had struck me. I used his neck cloth, and strips

torn from my own shirt, to put a splint on his broken leg. Then I made a

shelter for him, knowing it would rain again, and built a fire to keep him safe

from animals. I knew his son must be nearby and would search for him before

long. I put my own shirt on him to keep him warm, and over it his waistcoat and

coat again. Then I went to the camp of the Blackfeet. My brother Silent Wolf

knows the ways to take the thunder spirit out of my brain, before I harm those

around me. I was in their camp—' He frowned, trying to remember.

'Two nights.

Then Tall Chief and Winter Moon came - Bo Frye, too, and the Beauty. They told

me that old Bodenschatz had been found dead. I returned to my own camp and left

the rendezvous.'

'So when you

left the old man,' reiterated January, 'he was wearing your shirt - was this

the shirt you had bought from Ivy and Wallach the day before?'

'It was. Black

and yellow checks, cotton. Of good quality.'

'And his own

shirt was torn up for bandages around his ribs?'

Manitou nodded.

'What was that

shirt made of? What color was it?'

'White,' said

the trapper immediately. 'Linen—'

'Like the one

his son now wears?'

All eyes went to

Boden, who snapped, 'This is all lies!' He turned to Iron Heart, caught him by

the arm. 'This man talks nonsense, about what color our shirts are and who

wears what. What does it matter? He will say anything—'

'And I will

listen to anything,' replied the Omaha chief, his voice deadly quiet. 'The

truth leaves its tracks, like a fox in the snow, for a wise man to follow. Be

silent.'

Boden started to

reply, then looked around him, at the warriors who had moved in closer.

'Moccasin

Woman?'

Still with her

air of serene sadness, the matriarch opened her quillwork pouch and brought out

a bundle of cloth. The garments had been washed of their bloodstains, leaving

only pale brown ghosts, and the hole in the back of the checked shirt had been

neatly mended. Its torn-off hems had been sewn back as well - she must have

found those in the bushes around the camp, where Poco had thrown them and the

black silk cravat when he'd untied the splints. There wasn't a man among the

warriors - hunters and trackers from birth - who hadn't been brought up making

inferences from such details, putting together evidence in order to survive.

January summoned

back the two Omaha warriors who wore the old-fashioned black coat and the satin

vest with its outdated collar, and he held the black-and-yellow shirt up first

to one, and then the other. Walks Before rose from his blanket and studied the

holes, which matched one another exactly. Then January handed him the last

garment, the torn-up sections of the white linen shirt.

The seams had

been ripped apart, and one sleeve was missing—

'I got that

here.' Manitou slipped his left arm free of his deer-hide hunting-shirt, to

show the filthy, bloodied white linen that bound the bullet wound in his own

arm. 'You can see the cloth's the same.'

The back of old

Klaus Bodenschatz's white linen shirt was intact.

'He was stabbed,

then,

after

Manitou's

black-and-yellow shirt was put on him,' said Walks Before Sunrise, holding the

two garments in his hands. 'There was a great bleeding here, more than he would

have bled had his throat been cut earlier . . . And indeed, if his throat had

been cut first, what need to stab him in the back? What have you to say to

this, Boden?'

'That he's

lying,' argued Boden frantically. 'That that lying monster came back and

stabbed him later—'

'Why would he

have done that?' asked Walks Before reasonably. 'The old man's leg was broken.

He was no danger to Manitou then. Why not kill him the first time, rather than

build a shelter for him and bind his wounds?'

January folded

his arms, looked steadily at Bodenschatz where he stood among the Omahas. 'But

that broken leg meant that your father was now a liability to

you

,' he said

softly. 'You knew where your enemy was - and you knew that, having seen your

father, he would flee. Yet you couldn't pursue him as long as you had to care

for the old man. You'd have to take your father back to the settlements.

Certainly, your Omaha brothers weren't going to do it—'

'I—I knew

nothing of it,' Bodenschatz stammered. 'I didn't know he was dead until they

brought him into the camp—'

'But it was your

hat that one of the camp whores found beside the body later that morning,' said

January. 'With your hair in it, dyed black except for the brown at the roots—'

Sharply, the

young Omaha Kills With A Rock put in, 'He renewed the false color on his hair

the day he left our lodges, to ride into the white men's camp as a trader! It

was, as you say, brown as a raccoon's fur where it grew from his head, to the

length of a child's knuckle.'

'And the old

man's pistols were in your pockets yesterday. None were found on the body by

the men who took his coat. Yet he'd shot Manitou with one of them, and the

other had fired, putting a bullet into a tree, so he had them that night. And

as well as all that, Boden,' added January grimly, '

no

one else had any reason to kill him.

He was harmless, he was crippled, he was in a foreign land. He needed help,

that only his son could give him—'

'He would never

have asked me to give up my revenge!' shouted Boden. 'He was as vowed to it as

I!'

'Maybe he mighta

changed his mind,' put in Shaw softly, 'whilst lyin' there listenin' to the

rain? Let's see what's in that camp chest, Maestro—'