The Short Reign of Pippin IV (13 page)

Read The Short Reign of Pippin IV Online

Authors: John Steinbeck

“These paintingsâ” Uncle Charlie began.

“You say Boucher. I halfway remember him from Art Appreciation. Suppose I buy a Boucher with no signature. Know what will happen? Father will get an expertâhe's hell on experts. And suppose this Boucher is a phony. You see the position I'd be inâhustling my own father.”

“But a signature would save you that difficulty?”

“It would help. Understand, it wouldn't be certain. My father is no dope.”

“Perhaps we had better look at something else,” said Uncle Charlie. “I know where I can put my hand on a very nice Matisse

with

a signature. There is a âTête de Femme' of Roualt, very fineâor maybe you would like to see a veritable swarm of Pasquins. These will have a great future value.”

with

a signature. There is a âTête de Femme' of Roualt, very fineâor maybe you would like to see a veritable swarm of Pasquins. These will have a great future value.”

“I'd like to look at everything,” said Tod. “Bugsy said you were doing something wrong with the martinis.”

“They do not taste the same.”

“Are you getting them cold enough? Mac Kriendler once told me that the only good martini is a cold martini. Here, let me mix you one. Will you have one too, sir?”

“Thank you. I should like to discuss with you your father, the king.”

“Egg King.”

“Exactly. Has he been this for a long time?”

“Since the depression. He hit bottom then. That was before I was born.”

“Then he invented his kingdom as he went along?”

“You might say that, sir. And in his line there is nobody who can touch him.”

“He has a principality, your father?”

“Well, it's a corporationâkind of the same thing if you control the stock.”

“My young friend, I hope you will come to see me very soon. I wish to discuss the king business with you.”

“Where do you live, sir? Bugsy wouldn't ever tell me. I thought she was ashamed.”

“Perhaps she was,” said the king. “I live at the Palace at Versailles.”

“Holy mackerel!” said Tod. “Wait till my old man hears thisâ”

As though in celebration of the king's return, the summer slipped benignly over Franceâwarm, but not hot; cool, but not cold.

The rains waited until the flowers of the vines exchanged their pollen and set their clusters densely, and then gentle moisture stirred the growth. The earth gave sugar and the warm air breed. Before a single grape ripened, it was felt that, barring some ugly trick by nature, this would be a vintage year, the kind remembered from the time when an old man was young.

And the wheat headed full and yellow. The butter took an unearthly sweetness from the vintage grass. The truffles crowded one another under the ground. The geese happily stuffed themselves until their livers nearly burst. The farmers complained, as their duty demanded, but even their complaints had a cheerful tone.

From overseas the tourists boiled in and every one of them was rich and appreciative so that the porters were seen to smileâwhether you believe it or not. Taxi drivers scowled in a good-humored way, and one or two were heard to say that perhaps ruin would not come this year, an admission they will not care to have repeated.

And what of the political groups now firmly rooted in the Privy Council? Even they had an era of good feeling. Christian Christians saw the churches full. Christian Atheists saw them empty.

The Socialists went happily about writing their own constitution for France.

The Communists were very busy explaining to one another a shift in the party line which seemed to place leadership in the hands of the people, a subtlety later to be explained and exploited. Besides this, the collective leadership in the Kremlin not only had congratulated the French Crown but had offered a tremendous loan.

Alexis Kroupoff, writing in

Pravda,

proved beyond question that Lenin had foreseen this move on the part of the French and had approved of it as a step in the direction of eventual socialization. This explanation put the French Communists under an obligation not only to tolerate but actually to support the monarchy.

Pravda,

proved beyond question that Lenin had foreseen this move on the part of the French and had approved of it as a step in the direction of eventual socialization. This explanation put the French Communists under an obligation not only to tolerate but actually to support the monarchy.

The Non-Tax-Payers' League was lulled to a state of bliss, since American and Russian loans made it unnecessary to collect any taxes at all. A few pessimists argued that there would come a day of reckoning, but these were laughed to scorn as prophets of gloom and pilloried by caricatures in nearly all the French press.

The French Rotary Club grew to such proportions that it achieved the strength and influence of a party itself.

The landlords prepared their plan for government subsidy in addition to a rise in rent ceilings.

Right and Left Centrists were so confident of the future that they freely suggested a rise in prices together with a lowering of wages, and no riots ensued, which proved to most people that the Communists had indeed been defanged.

To such a stable government there was no end to the loans America was happy to advance. The outpouring of American money had the effect of strengthening the Royalist parties of Portugal, Spain, and Italy.

England looked dourly on.

At Versailles the nobility happily quarreled over an honors list of four thousand names while a secret committee went forward with plans for restoring the land of France to its ancient and obviously its proper owners.

As Marie was one of the first to point out, it was the king this and the king that . . . No one will ever know what the queen went through. Being a queen takes some doing, but you are never going to make a man understand this. Marie had ladies in waiting, certainly, but just ask a lady in waiting to do something and see where you get. And it wasn't as though there were nearly enough servants and what there were were public servants who would argue for an hour rather than turn a dust cloth and then complain to the privy councilor who had procured the appointment.

Consider, for a moment, that gigantic old dustbox Versailles. How could any human being keep it clean? The halls and stair-cases and chandeliers and corners and wainscoting seemed to draw dust. There had never been any plumbing worth mentioning inside the place, although there were millions of pipes to the fountains and the fish ponds outside.

The kitchens were miles away from the apartments, and just try to get a modern servant to carry a covered tray from the kitchens to the royal apartments. The king could not eat his meals in the state dining rooms. If he did he would have two hundred dinner guests, and the royal family were just managing to scrape by as it was. In dividing the royal monies nobody gave a thought to the queen. She ran from morning until night, and still the housekeeping kept ahead of her. The extravagance was enough to drive a good Frenchwoman insane.

Besides all this, there were the nobles in residence. Their bowings and scrapings and grand manners disgusted Marie. They were always deferring to her opinion and then not listening, particularly when she asked themâasked them nicely, mind youâplease to turn out the lights when they left a room, please to pick up their dirty clothes, please to clean the bathtub after themselves. But it was worse than that. They ignored her requests that they stop breaking up the furniture to burn in the fireplaces, stop emptying their chamber pots in the garden. It was impossible for Marie to figure to herself how such people could live with themselves.

And would the king listen? King indeed! He had his head in the clouds even more than he had when he played at being an astronomer.

Clotilde was no help to her. Clotilde was in love, not in love like a well-brought-up French girl, but in slob-love like an American student at the Sorbonne. And Clotilde had gotten so grand or so forgetful that she no longer made her bed or even washed out her underthings.

Worst of all, Marie had no one to talk to, to complain to, to gossip with.

There is no doubt that every woman needs another woman now and then as an escape valve for the pressures of being a woman. For her the man's releases are not available, the killing of small or large animals, vicarious murder from a seat at the prize ring. Flight into the hidden kingdom of the abstract is denied her. The Church and the confessor can let out some of the tensions, but even that is sometimes not enough.

Marie needed the sanctuary of another woman. Her good sense revolted against the ladies in waiting and the intolerable corps of nobles. Being queen, she was fearful of old friends of her Marigny days, because they could not fail to use their fancied influence in the interest of their husbands.

Queen Marie, casting in her mind, thought of her old friend and schoolmate Suzanne Lescault.

Sister Hyacinthe was perfect as a companion to the queen. Her order was able to change a rule and to uncloister the nun upon recognition of certain advantages which might accrue to itself as well as the natural satisfaction of knowing that the dear queen was in good hands. Sister Hyacinthe was removed to Versailles and encelled in a lovely little room overlooking box hedges and a carp poolâa few steps, indeed, from the royal apartments.

It may never be known exactly how much Sister Hyacinthe contributed to the peace and security of France. For example:

The queen closed the door firmly, put her fists on her hips, and breathed so tightly that her nostrils whitened. “Suzanne, I'm not going to put up with that dirty Duchess of Pââanother minuteâthe insulting, insufferable slut. Do you know what she said to me?”

“Gently, Marie,” said Sister Hyacinthe. “Gently, my dear.”

“What do you mean gently? I don't have to sufferâ”

“Of course not, dear. Hand me a cigarette, will you?”

“What am I going to do?” the queen cried.

Sister Hyacinthe slipped a hairpin around the cigarette to keep stain from her fingers, and she blew the smoke from lips pursed to whistle. “Ask the duchess if she ever hears from Gogi!”

“Who?”

“Gogi,” said Sister Hyacinthe. “He was a high-wire man, very handsome, but nervous. So many artists are.”

“Ha!” said Marie, “I understand. I'll do it! Then we'll see what she does with her lifted face.”

“You mean those scars, dear? No. Her face was not lifted. It was, you might say, dropped. Gogi was very nervous.”

Marie charged for the door, her eyes shining. Under her breath, as she searched the long painted halls, she muttered, “My dear Duchessâhave you heard from Gogi lately?”

Or again:

“Suzanne, the king is being a bore about this mistress business. The Privy Council has appealed to me. Do you think you could talk to the king about it?”

“I have just the mistress for him,” said Sister Hyacinthe. “Grand-niece of our Superiorâquiet, well-bred, a little stocky, but, Marie, she does beautiful needlework. She could be valuable to you.”

“He won't consider her. He won't even discuss it.”

“He won't have to see her,” said Sister Hyacinthe. “In fact, it might be better if he didn't.”

Or again:

“I don't know what I'm going to do with Clotilde. She's sloppy and listless. She won't pick up her clothes. She's selfish and inattentive.”

“We have this problem in the order sometimes, dear, particularly with young girls who confuse other impulses with the religious.”

“And what do you do?”

“Walk calmly up to her and punch her in the nose.”

“What good will that do?”

“It will get her attention,” said Sister Hyacinthe.

The queen never regretted calling in her old friend. And in the palace the wayward nobility began to be nervously aware of a force, of an iron influence which could be neither ignored nor sneered out of existence.

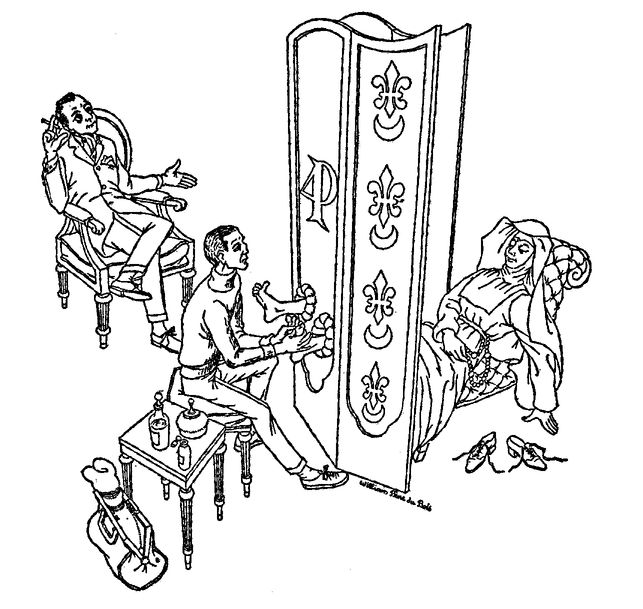

For her birthday, Marie presented Sister Hyacinthe with a daily foot massage by the best man in Paris. She ordered a tall screen with two holes near the bottom, through which Suzanne's feet and ankles could protrude.

“I don't know what I would do without her,” said the queen.

“What?” the king asked.

Â

Â

Pippin was in a state of shock for a long time. He said to himself in wonder and in fear, “I am the king and I don't even know what a king is.” He read the stories of his ancestors. “But they wanted to be kings,” he told himself. “At least most of them did. And some of them wanted to be more. There I have it. If I could only find some sense of mission, of divinity of purpose.”

He visited his uncle again. “Am I right in thinking that you would be glad if you were not related to me?” he asked.

Uncle Charlie said, “You take it too hard.”

“That's easy to say.”

“I know. And I'm sorry I said it. I am your loyal subject.”

“Well, suppose there were a revolt?”

“Do you want truth or loyalty?”

“I don't knowâboth, I guess.”

Other books

The Anvil of Ice by Michael Scott Rohan

Brother to Brother: The Sacred Brotherhood Book I by A.J. Downey

William W. Johnstone by Massacre Mountain

From Ashes by Molly McAdams

Good Girls Don't by Claire Hennessy

Green Darkness by Anya Seton

Beyond the Rules by Doranna Durgin

1,000-Year Voyage by John Russell Fearn

The Invention of Murder by Judith Flanders

Bad Games by Jeff Menapace