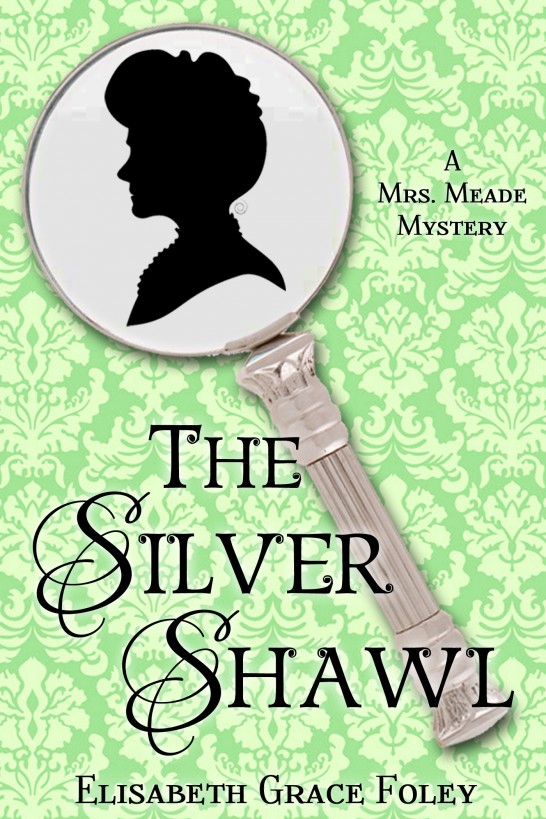

The Silver Shawl

Authors: Elisabeth Grace Foley

Tags: #historical mystery short mystery cozy mystery novelette lady detective woman sleuth historical fiction colorado

The Silver Shawl: A Mrs. Meade Mystery

By Elisabeth Grace Foley

Cover design by Historical Editorial

Silhouette artwork by Casey Koester

Photo credits

Victorian wallpaper © mg121977 | Fotolia.com

Magnifying glass © mvp | Fotolia.com

This e-book is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. This e-book may not be re-sold or given away to other people.

If you would like to share this book with another person, please

purchase an additional copy for each person. If you’re reading this

book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use

only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own

copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Copyright © 2012 Elisabeth Grace Foley

For a limited time, get the second book in the Mrs.

Meade Mysteries series for free when you subscribe to the Second

Sentence Press new release newsletter! Sign up here:

http://eepurl.com/biZJDb

Table of Contents

GLOUCESTER. In my opinion yet thou seest not

well.

SIMCOX. Yes, master, clear as day, I thank God and

St. Alban.

GLOUCESTER. Say’st thou me so? What colour is this

cloak of?

- William Shakespeare, Henry VI.

Mrs. Henney knocked lightly at the door. The

early morning sunlight was streaming in through the potted plants

in the window at the end of the hall, over the faded strip of

carpet down the middle of the floor, and gleaming on the polished

wood of the door by which Mrs. Henney stood. Having waited with

lifted hand, but received no answer, she knocked again.

“Miss Charity?” she said. “Breakfast is

ready.”

She listened with her head tilted toward the

door, but there was no sound. Mrs. Henney smiled indulgently to

herself and turned away. Sleeping a little late, she didn’t

doubt—Miss Charity’d been that busy these last few weeks, and down

to Miss Lewis’s last evening as usual. No harm in letting her get a

bit of rest, Mrs. Henney thought as she descended the back stairs

to the kitchen—she would take a tray up to Miss Charity’s room

after she had served breakfast to her other ladies and

gentlemen.

(There was, strictly speaking, only one

elderly gentleman among Mrs. Henney’s boarders, but Mrs. Henney

always pluralized him when she referred to them as a group. It made

her little establishment sound so much more flourishing.)

Breakfast was over, and Mrs. Henney had just

finished clearing away the dishes from the dining-room to the

kitchen, when the front door banged smartly and Randall Morris took

the main stairs to the upstairs hall two at a time, whistling

merrily, his quirt swinging from his left hand. He stopped at the

same hall door and knocked. “Charity?” he called.

He waited a few seconds, as Mrs. Henney had

done, and then knocked again. “Charity, are you there?”

The door across the hall opened and Mrs.

Meade looked out. Randall Morris glanced over his shoulder.

“’Morning, Mrs. Meade,” he said, a friendly smile flashing across

his handsome face. “Say, is Charity in? I’ve got to go over to

Jewel Point to see Hart about a yearling, and I just stopped by to

see her on the way.”

“Good morning, Randall,” said Mrs. Meade,

smiling pleasantly up at him in return. She was a widow lady of

middle age, but one whom age seemed to have softened rather than

hardened. Her graying hair still showed hints of the soft brown it

had once been, and all the lines of her face were kind. But behind

the kindness in her gray-blue eyes there was an expression of

quaint humor, as though she knew a good deal more about you than

you realized, but was too kind to let you know it.

“Charity hasn’t been down this morning,” she

said. “Mrs. Henney told us she knocked at her door before

breakfast, but she didn’t answer. Mrs. Henney supposed she must

have been sleeping a little late.”

“That’s odd,” said Randall. He tried the

doorknob and found it locked, and knocked once more. “Charity!” he

called in a louder voice.

Mrs. Meade had drawn nearer, and they both

listened attentively, Randall with his ear close to the door, but

neither could hear any sound.

Randall cast an alarmed glance at Mrs. Meade.

“You don’t think she’s ill or something!” he said.

Without waiting for an answer he pounded on

the door with his fist in a way that startled all the other

boarders in their respective rooms, and then would have immediately

forced the door with his shoulder had not Mrs. Meade laid detaining

hands on his arm and prudently suggested applying to Mrs. Henney

for the spare key.

She performed this office herself, and when

she escorted the short and puffing landlady to the top of the

stairs Randall was still listening outside the door with a look of

strained anxiety.

“I can’t hear anything,” he said, and the

look in his eyes as he thus appealed to Mrs. Meade was almost

desperate.

Mrs. Meade put her hand gently on his arm as

they watched Mrs. Henney fumble nervously with the keys and at last

manage to insert the right one into the lock. The door opened

inwards, and Randall pushed unceremoniously past Mrs. Henney into

the room. He stopped in the middle of it, looking about him in

bewilderment.

The two ladies, who had entered after him in

considerable apprehension, likewise looked with astonishment about

the room, which was neat, quiet, and empty. The window-shade was

drawn halfway down, blocking out most of the morning light and

leaving the room mildly dim; the bed was neatly made and had

evidently not been slept in.

Randall Morris turned around to stare at the

ladies. “Did she go out this morning?” he said.

“Why, no,” said Mrs. Henney, whose mouth and

eyes were wide. “I was up early as always, and her door was shut

when I opened the curtains in the hall. She hasn’t come out

since.”

“But how do you know that? Couldn’t she have

gone out when you were getting breakfast?”

“Why, no, sir. I can hear every step on those

stairs, front or back, when I’m in my kitchen, and nobody went out

of the house this morning, not Miss Charity nor anybody.”

“Well, then—where is she? When did you see

her last?”

“Why, she went out to Miss Lewis’s last

evening after supper, Mr. Randall, just as usual. I saw her go out

then, and I was in bed and asleep before she came back, as I’ve

often been. I let Miss Charity have an outside key so she can come

in without waking anyone if it’s late and I’ve already locked up

and gone to bed.”

“You mean you didn’t see her come back last

night? or hear her?”

“Why, no, sir.”

Mrs. Meade, in the meantime, had with a

thoughtful expression crossed the room to the wardrobe and opened

it, and stood looking at the simple dresses hanging there. “The

dress she wore yesterday is not here,” she said. “She was wearing

her light green gingham at supper—”

“Yes, I know that dress,” blurted Randall

feverishly, as if that would be some help.

Mrs. Meade lifted a hatbox a few inches from

the floor of the wardrobe and shook it gently, and set it down

again. “Her summer hat is missing—and her little silk purse, it

seems—but everything else appears to be in order. She was wearing

that hat when she went out, wasn’t she, Mrs. Henney?”

“Yes, yes, that and her shawl. That’s what

she had on when I saw her go out and—”

Randall interrupted the landlady’s trembling

recollections, speaking to Mrs. Meade: “Do you mean she didn’t come

back last night? Then where—”

Mrs. Meade countered the alarm rising in his

voice with a calm interruption of her own. “Perhaps she spent the

night with Miss Lewis, if their work went very late. Miss Lewis

stays at the shop herself some nights if she doesn’t feel equal to

walking home. You should go and ask her first of all.”

“I’ll do it,” said Randall breathlessly, and

plunged out of the room. In a few seconds he was outside untying

his horse from Mrs. Henney’s gate, and swung up into the saddle. He

brought his quirt down sharply across the horse’s glossy flank and

spurred out of the quiet side street into the main road.

* * *

Sour Springs, Colorado, misnamed by an early

settler who did not care for the taste of the mineral water he had

found on his land, was a pleasant little mountainside town nestled

among the wooded foothills, with pine forests on the crests and

lighter green stretches of cultivated farm and ranch land in the

valleys between. The snow-crested Rockies all around made a sharp

silver and white frame for the dome of clear blue sky arched over

it. The sunny main street was a double row of neat frame houses and

storefronts punctuated by fenced, tree-shaded side lawns and

gardens.

Randall Morris, the son of a Southern family

whose fortunes had suffered in the generations following the war,

had come West to make his own way in the world several years

before. Young, energetic and determined, he was already well on his

way to success, breeding and raising horses that bid fair to be as

fine as those of Kentucky or Virginia on the slopes of his land at

the foot of the mountains. Over the past few months, during his

courtship of Charity Bradford, he had spent much of his time

building and furnishing a house there. Half Western ranch house,

sturdy and square and practical, yet partaking of some of the

patrician elegance he remembered from his youth, with its

many-paned windows and wide veranda, it gleamed white and pristine

among the pines, with wild roses tumbling over themselves in the

rocky garden behind it, awaiting its mistress.

Charity was a relative newcomer to Sour

Springs, a girl without friends or relatives who had come there

seeking work, and had been employed as assistant postmistress at

the little post-office that shared a building with the railway

depot. Small and dainty, with a sweet voice and rich brown hair,

she had a modest, if not quite reserved demeanor, but to those she

trusted was capable of a warmth made all the more precious by being

hard-won. Randall Morris had fallen tumultuously in love at almost

his first sight of her, and immediately devoted his considerable

energies to wooing and winning her. Charity had been cautious at

first—perhaps as long as it took her to assure herself that his

impetuosity was in fact sincerity, though, truth be told, her heart

had succumbed almost as soon as his.

Within the year they were engaged, and for

the past month Charity had been busy preparing her trousseau, her

days passed in a near trance of serene happiness and enlivened by

flying visits from her fiancé at all hours of the morning and

evening. Randall was a great favorite with the ladies of the

boarding-house that had become Charity’s home. His manners were

both free-and-easy and charming, and he knew how to be attentive to

old ladies as well as young ones—though when Charity was present,

he was infallibly absorbed in her to the extent that he never saw

the knowing nods and smiles and twitters passed among the ladies as

they watched the pair. Some of the ladies went so far as to believe

they had made the match themselves, but Mrs. Meade, who had a

special place in her heart for young people—especially young people

in love—knew better.

Randall pulled up his horse in front of a

small dry-goods store on the main street and dismounted. The

seamstress who was making Charity’s dresses rented rooms above the

store, and Charity had been visiting her in the evenings for

fittings and to assist her in some of the work. With no dowry and

little money of her own, Charity had at first been hesitant to

accept Randall’s insistence on paying for everything himself, but

had eventually relented. She had, however, managed to override his

expressed opinion that nothing was too good for her, and earnestly

endeavored to keep her expenses as modest as possible.

Randall went up the steps to the store and

grasped the doorknob, but encountered an unexpected resistance. It

was locked. He rattled the door and knocked loudly, and then

looking over at the front windows, saw that the shades were drawn.

The storekeeper and his family lived at the back of the building,

and ordinarily the store was already open for business at this

hour. In Randall’s disturbed state this was yet another

circumstance for alarm. He pounded on the door again. Only silence

succeeded.

Randall was looking about him with a confused

idea of doing something desperate to attract attention, such as

throwing something at an upstairs window, when at last he heard a

faint noise. Someone was coming down the stairs inside. The locks

of the door scraped as they were turned, and it opened to reveal

Diana Lewis, the seamstress.