The Silver Spoon (22 page)

Authors: Kansuke Naka

10

The school subject I hated above all else was ethics. In the senior classes they gave up the hanging scrolls and used a textbook instead. But for some reason it had a grubby cover, clumsy illustrations, and both its paper and the printing were coarse and bad. It was such a shoddy book, it made you feel creepy just picking it up in your hands. The stories it carried were worse, all about such things as a son full of filial piety given an award by the lord of his domain or an honest man becoming rich, every one of them told with no taste or flair. On top of this, the teacher had no ability beyond adding utilitarian explanations in the basest sense of the word. In consequence, ethics not only utterly failed to make me good-natured in any way but even created exactly the opposite result. Even in view of what meager things a mere eleven- or twelve-year-old child had seen and heard or experienced on his own, I could not believe these stories as they were. I thought ethics books were there to deceive people. So, during this fearful hour in which bad manners were said to deserve reduced marks for conduct, I deliberately behaved as poorly as I could to let my irrepressible resentment be knownâpropping up my chin with a hand, looking around distractedly, yawning, or humming.

After I started school, I must have been taught the phrase “filial piety”

37

a million times. However, their “Way of Filial Piety,” when all was said and done, was based on gratitude, that it was our supreme happiness to be given life in this particular fashion and to continue that life in this particular fashion. How could that have any authority for a child like me who had begun to feel the pain of life early on? Wanting to know clearly what the reason was, I once asked the following question on filial piety, which everyone had swallowed whole and been afraid of touching as though it were a malignant abscess.

“Sir, why should anyone show filial piety?”

The teacher rounded his eyes in astonishment. “Because you are able to eat when you are hungry, take medicine when you are ill, thanks to your father and mother,” he said.

“But I do not want to live all that much.”

His displeasure became pronounced. “Because it's higher than the mountain and deeper than the sea.”

38

“But my filial piety was much greater before I knew any such thing.”

The teacher flared up. “Those of you who understand filial piety, raise your hands.”

All the buffoons raised their hands at once and stared rudely at me even while I, almost bursting with fury at this unreasonable, treacherous ruse, was unable to raise my hand, blushing with embarrassment that I was the only one who couldn't. Chagrined though I was, I could not say anything further and fell silent. After this the teacher always used this effective means to shut off my questions. On my part, to avoid this humiliation, I began to not go to school whenever there was an ethics class.

11

One night someone suddenly suggested we go to the ShÅrin temple to play, so we did. In the temple lived a boy called Sada-chan who was one year below me both in age and grade, and even though I had seen him and knew him, time had passed with no opportunity for me to make friends with him or to hope to do so. Because it was my first time like this, I passed through the doorless main gate with considerable anxiety and curiosity. We went to a spot under the magnolia tree near a well I remembered seeing before and took turns calling his name until Sada-chan opened the door into the inner foyer with a clatter and guided us into the dining room.

For me, an unexpected guest, Sada-chan's family had taken out a hanging lamp that they saved for just such an occasion. An old model one seldom saw even in those days, the lamp was in a square glass box. Under the bright light that it cast dazzlingly above and below, to the left and right, we became absorbed in games such as Dominos

39

and Traveling with Dice.

40

I remember how the latter had a picture of a bonito-seller at the Nihon Bridge

41

that was the game's starting point and how Sada-chan's family laughed when I read the two characters for Goyu

42

as

“o-abura.”

It was the first night game I had ever played in my life, and I was also happy that Sada-chan's family, merry and apparently fond of children, played with us. Even though it was the first time I'd met them, I became quite excited playing with them.

True, with my sickliness as an excuse, I was, among my siblings, treated the most generously and had indeed behaved in a very spoiled manner. Nevertheless, worried as I was about all the restrictions posted up in every direction, no matter what I didâwhether I walked, breathed, sat, or lay down to sleepâI had never played in the way a child should and did not have a place to play, either. As a result, that space inside the doorless main gate, which seemed liberated for the sort of child I was, became, to me, a place of freedom that I cannot possibly forget. With this first visit as impetus, I began going there to play every three days or even oftener. Indeed, as a place where an unchildlike child, who for a variety of reasons had lost many of the happy characteristics that an ordinary child is supposed to have, such as innocence and cheerfulness, was able to spend joyful, unselfconscious moments like a truly childlike child; as a place where a withdrawn, melancholy child could store childlike knowledge about nature that could be endowed only out in the sunshine; and as a place where I was able to nurture and develop a certain innate characterâa character that to my brother was quite disreputableâthat shaped what I would later become, the precincts of the ShÅrin temple have a special meaning for me.

The temple once counted shogunate aides-de-camp among its chief parishioners and was famous enough to be in a pictorial guide to Edo. But after the Restoration most of those people scattered away, and even the few who happened to stay on had declined in fortune. Naturally, the temple had fallen into worse difficulties than had been expected and was deteriorating every year. Even so, it retained most of the features it had when I used to visit it on my aunt's back: The peacock on the screen in the foyer still proudly drooped his gorgeous tail and, around the peony flowers variously blooming, butterflies continued to dance as if intoxicated with the dreams of the past.

Beyond a tall hedge covered with Chinese hawthorns and to the left was the kitchen. And if you went there and turned right, there was a courtyard with flowerbeds and strawberry patches and old trees left uncut, casting large dark shadows here and there. If you turned right there again to make an L shape, in one corner of the garden of the main hall facing west stood a large black pine with its rock-knob-like roots rioting into the middle of the garden and its branches extending every which way, forming, for hundreds of pilgrim monks, a green heavenly cover and, for us, a shelter from evening showers and cool shade from the summer sun. Daikon radishes and rape would flower in the bluff-side vegetable patch further down. And in a thicket all jumbled up with snake-gourds and sorrel vines was an old well from the bottom of which mosquitoes sometimes would glide up toward you. If, from behind the black pine, you took the dog's path on the embankment covered with bear grass,

43

you popped out suddenly on the north side, into an open space, which was a cemetery with chestnut trees growing all over the place, everything buried under chestnut flowers, leaves, and burrs, and on the brownish stained grave stones you could often see land planarians

44

crawling about.

Sada-chan was a good-natured boy and a clown and he happily complied with whatever wishes I made, while I hadn't done much playing outdoors before and totally lacked the knowledge it needed. So he served as my teacher in such things, and the two of us became good playmates.

12

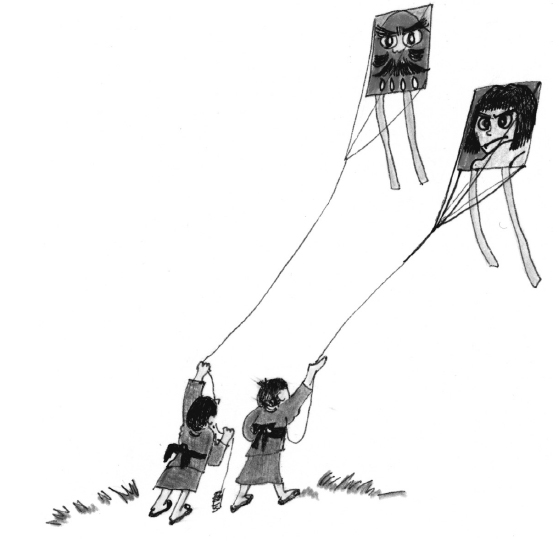

In spring we would go to the spacious field over a hill and fly kites. Sada-chan's was a bearded Dharma, and mine a KintarÅ on a square-latticed frame. At first a kite, with its string held down, utterly submits itself to your whims, but as it rises, it begins to behave haughtily, in the end controlling you the flyer who, via a single string, is gazing up at the sky rapturously. Humming, swaying its tail languorously, the kite looks as if it is swimming in the ocean of the big sky. When the tautness becomes strong enough to start pulling you, or when the kite, annoyed by something, begins to turn round and round, you become scared and, calling out, Forgive me! Forgive me!, give out more string from the spool until it regains its good mood.

What was terrifying was the Boy's-Lattice

45

with eight parts that the son of the head of a construction crew

46

flew. Its jutting-whistle made of rattan let out a thrilling sound while the end of the kite's long tail leapt powerfully up and the rasp attached to the balancing strings glistened, glistened. Everyone disliked the two-part kite with a Hangya

47

that a bully from a lower part of town flew. This fellow's intention was to fight others from the start, for his was a

motten

48

without even a tail and he raised it jerkily, threateningly, as it made a disgusting peeping noise with its paper-whistle. The Hangya, frowning even more horribly than usual with its central balancing strings drawn tight, madly snapped at her neighboring kites, in no time chewing apart their threads with a newly invented anchor-rasp.

TAKOAGE:

KITE-FLYING

Before setting off, we would check to see that there weren't any fighting kites. As you walk with the heavy spool in one hand, the other hand holding the balancing strings as if on to a bit, your kite, jumpy as a racehorse, tries to leap out and away. Among the kites up in the windy spring sky with self-assured vigor, my KintarÅ on its shoji frame, perhaps because of my own conceit, looks particularly conspicuous. While flying kites, you become oblivious to everything else. The other children all go home, leaving only the two of you in the darkening field. Noticing this, you're suddenly scared and start pulling the strings, but it is just at such times that the strings seem particularly taut and the more pressed you feel, the less able you are to bring your kite down. The sun continues to sink, and all you see in a sky that is growing darker minute by minute are the KintarÅ and the Dharma's glaring eyes. Each of you knows how the other is feeling but, hating to give in, you maintain your careless miens even while worrying, What'll I do if I can't bring my kite down until after nightfall, I shouldn't have let out all the string, and so on. When you bring down your kites at long last and finish winding up the strings, you feel what's been filling up your chests dissipate suddenly and, looking at each other, you burst out laughing, Ha-ha-ha-ha. Still, one of you will admit the truth: “A minute ago I didn't know what to do.”

“Let's not tell anybody,” you promise firmly before going home.

13

In summer we frittered away our carefree lives catching cicadas. Saying, You spoil their wings if you catch them with birdlime, we would attach a sugar-cube bag to the end of a pole and walk from the garden to the cemetery looking for them. With so many trees, we caught a disgustingly large number of them just by going through the place once. The “oily cicadas”

49

are merely noisy and don't look nice, so catching them doesn't particularly elate you. The “

minmin

cicadas”

50

are roly-poly fat and their chirps are clownish. The “monk cicadas”

51

have an interesting song; besides, they're so swift you chase them as if they were your mortal enemies. You can't do anything with “darkening cicadas.”

52

The “mute cicada”

53

struggling in your bag without uttering a sound breaks your heart.

Also, in each season we would move from one fruiting tree to another like birds looking for food. After a Japanese plum

54

scatters its flowers, pale-blue, you impatiently watch its bean-sized fruit swell from day to day, until they grow to the size of a sparrow egg, then to that of a pigeon egg, acquiring a yellow tint, then a reddish one like your cheeks, branches finally bending to touch the ground. Then, though you know you'll get permission “as long as you don't get a bellyache,” you secretly, and continuously, pluck and eat them until you have a plum belch. Even then you can't eat them all, and those that turn purple, overripe, splotch down. Crows come over for them and peck at them swaying their tails hatefully.

What we looked forward to were the chestnuts in their prime. One of us holding a bamboo pole, the other carrying a basket, we would walk in the cemetery “with a cormorant eye, a hawk eye.”

55

What a joy it was to find ripened ones as if ready to drop like dew. Rap it lightly with the tip of your pole and the burr shakes its head giving a truly delicious response. So you give it a hard knock. The chestnuts patter down. You rush to them and pick them up. And eat at least one of the three just to see. Strawberries. Persimmons.