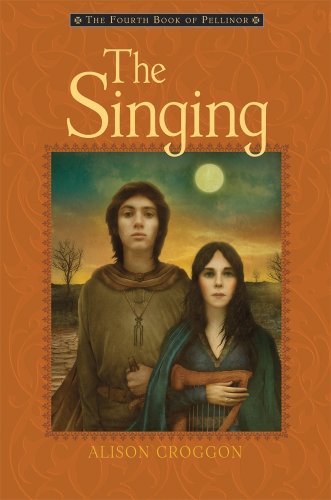

The Singing

Authors: Alison Croggon

THE SINGING

THE FOURTH BOOK OF PELLINOR

ALISON CROGGON

CANDLEWICK PRESS

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author's imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2008 by Alison Croggon Maps drawn by Niroot Puttapipat

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher.

First Candlewick Press edition 2009 First published by Penguin Books, Australia Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Croggon, Alison, date. The singing / Alison Croggon. —1st U.S. ed. p. cm.—(The fourth book of Pellinor) Summary: The bard Maerad and her brother Hem hold the key to the mysterious Singing, and each of them must overcome terrible obstacles before they can unite and together unlock the Tree of Song, release the music of the Elidhu, and defeat the Nameless One. ISBN 978-0-7636-3665-4 [1. Brothers and sisters—Fiction. 2. Orphans—Fiction. 3. Supernatural—Fiction. 4. Magic—Fiction. 5. Fantasy] I. Title. II. Series. PZ7.C8765Si 2009 [Fic]—dc22 2008017494

2468 10 97531

Printed in the United States of America

This book was typeset in Palatino.

Candlewick Press 99 Dover Street Somerville, Massachusetts 02144

visit us at

www.candlewick.com

One

is the singer, hidden from sunlight Two is the seeker, fleeing from shadows Three is the journey, taken in danger Four are the riddles, answered in treesong: Earth, fire, water, air Spells you OUT!

Traditional Annaren nursery rhyme Annaren Scrolls, Library of Busk

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

It is with mixed feelings that I have at last finished my task of translating the

Naraudh Lar-Chane,

the

Riddle of the Treesong.

On the one hand, I write this with the intense relief, not to say euphoria, that attends the end of any long labor; on the other, its completion will leave a large gap in my life. I will miss Maerad, Cadvan, Hem, Saliman, and their many friends; in the past seven years they have become as real to me as anyone in my life. I feel as if I have journeyed with them and shared their joys and sorrows, and now I must leave them behind and turn to the more sober demands of my academic profession, from which this has been the most pleasurable diversion imaginable.

The past three volumes translate the first six books of this great epic of Annaren literature.

In

The Naming,

we follow Maerad's adventures as she meets the Bard Cadvan of Lirigon, learns her destiny and true identity, and journeys to Norloch, the great citadel of the Light in Annar, discovering her lost brother, Hem, on the way. In Norloch, Maerad and Cadvan find the Light is corrupted and are forced to flee as civil war breaks out among the Bards of Annar.

In the second volume,

The Riddle,

Maerad travels with Cadvan to the frozen wastelands of the north in search of the Treesong. After a skirmish in which she believes Cadvan is killed, she journeys to the deep north, where she is told that half of the Treesong is written on her own lyre. On her way back, she is captured by the powerful Elidhu, Arkan, the Winterking, but escapes his clutches and is reunited with Cadvan.

The Crow

shifts focus to follow Hem's story. Hem travels with the Bard Saliman to the city of Turbansk and is embroiled in the great battles in the south, when the Nameless One marches on the Suderain and lays siege to Turbansk. Hem's dark journey to the Nameless One's stronghold, Dagra, in the heart of Den Raven, is the nadir of the story.

In

The Singing,

which consists of the final two books of the

Naraudh Lar-Chane,

the story of the quest for the Treesong reaches its end. I will leave it to the reader to discover the story; but I will say that I probably enjoyed my task most in these final books.

In the course of the books, we encounter some of the diverse cultures of Edil-Amarandh, and we learn a lot about the place of Barding in this society, further details of which I have endeavored to provide in the appendices in the three previous books. I have always considered this story more than just a source of information about these cultures; in its own time, I have no doubt that it was treasured as much for its delights as its usefulness.

The

Naraudh Lar-Chane

was, according to popular tradition, written by Maerad and Cadvan themselves, although some scholars dispute this authorship and claim it was written decades after their deaths, drawing from oral traditions. I have little interest in these arguments myself, just as I am not very concerned about the disputes regarding the authorship of Shakespeare's plays; what has always excited me most is the story itself.

For reasons that scholars can only guess, the histories come to an abrupt and unexplained end in about N1500, around five hundred years after the events of the

Naraudh Lar-Chane.

The most popular theory is that the civilization of Edil-Amarandh was destroyed by a major cataclysm caused by a meteor striking the earth. Like so many aspects of Annaren lore, the truth remains a teasing mystery. All that is known for sure is that this fascinating society vanished, leaving nothing behind except the strangely enigmatic traces preserved in the Annaren Scrolls.

I owe thanks to so many people that I do not have the space to acknowledge them all here. Firstly, as always, I want to thank my family for their patience and help over the years while I was working on this translation—my husband, Daniel Keene, for his support of this project and his proofing skills, and my children, Joshua, Zoe, and Ben. I am again grateful to Richard, Jan, Nicholas, and Veryan Croggon for their generous feedback on early drafts of the translation. I owe a special debt to my editor, Chris Kloet, whose sharp eye and good advice have improved on my own work beyond measure; it has been an unfailingly pleasurable collaboration. My debt to the generous and creative contributions of my colleague Professor Patrick Insole, now Regius Professor of Ancient Languages at the University of Leeds, is also beyond measure. Equally, I would like to thank my many colleagues who have so kindly helped me with suggestions and advice over what has now been many years of delightful conversations; they are too numerous to name, but I am grateful to them all—their help has been beyond priceless, and any oversights or errors that remain after such advice are all my own. Lastly, I would again like to acknowledge the unfailing courtesy and helpfulness of the staff of the Libridha Museum at the University of Queretaro during the months I spent there researching the

Naraudh Lar-Chane.

Alison Croggon Melbourne, Australia

A NOTE ON PRONUNCIATION

M

OST Annaren proper nouns derive from the Speech, and generally share its pronunciation. In words of three or more syllables, (e.g.,

invisible)

the stress is usually laid on

the second syllable: in words of two syllables, (e.g.,

lembel)

stress is always on the first. There are some exceptions in proper names; the names

Pellinor

and

Annar,

for example, are pronounced with the stress on the first syllable.

Spellings are mainly phonetic.

a

—as in

flat. Ar

rhymes with

bar.

ae

—a long

i

sound, as in

ice. Maerad

is pronounced

MY-rad.

ae

—two syllables pronounced separately, to sound

eye-ee. Maninae

is pronounced

man-IN-eye-ee.

ai

—rhymes with

hay. Innail

rhymes with

nail.

au—

ow. Raw

rhymes with

sour.

e

—as in

get.

Always pronounced at the end of a word: for example,

remane, to walk,

has three syllables. Sometimes this is indicated with

e,

which indicates also that the stress of the word lies on the

e

(for example,

He, we,

is sometimes pronounced almost to lose the

i

sound).

ea

—the two vowel sounds are pronounced separately, to make the sound

ay-uh. Inasfrea, to walk,

thus sounds:

in-ASS-fray-uh.

eu—

oi

sound, as in

boy.

i

—as in

hit.

ia

—two vowels pronounced separately, as in the name

lan.

y—

uh

sound, as in

much.

c—always a hard c, as in

crust,

not

ice.

ch—soft, as in the German

ach

or

loch,

not

church.

dh—a consonantal sound halfway between a hard

d

and a hard

th,

as in

the,

not

thought.

There is no equivalent in English; it is best approximated by hard

th. Medhyl

can be said

METH'l.

s

—always soft, as in

soft,

not

noise.

Note:

Den Raven

does not derive from the Speech, but from the southern tongues. It is pronounced

Don RAH-ven.

I

am the Lily that stands in the still waters, and the morning sun

alights on me, amber and rose; I am delicate, as the mist is delicate that climbs with the dawn; yea, the

smallest breath of the wind will stir me. And yet my roots run deep as the Song, and my crown is mightier

than the sky itself, And my heart is a white flame that dances in its joy, and its light will

never be quenched. Though the Dark One comes in all his strength, I shall not be

daunted.

Though he attack with his mighty armies, though he strike with iron

and fire, with all his grievous weapons, Even should he turn his deadly eye upon me, fear will not defeat me. I will arise, and he will be shaken where he stands, and his sword

will be shivered in the dust, For he is blind and knows nothing of love, and it will be love that

defeats him.

From

The Song of Maerad,

Itilan of Turbansk

I