The Sinking of the Bismarck (7 page)

Read The Sinking of the Bismarck Online

Authors: William L. Shirer

The truth was, as the German admiral realized, that he was still too far from land for the German bombers to be of any help to him. Even the longer-range German reconnaissance planes could not find the British pursuers in the low visibility of the storm. The

Bismarck

herself had had to reduce speed in the rough seas for fear of worsening the damage to her side and to her oil tanks.

Still, she was plowing along at twenty knots and her big guns were in tip-top shape. She had finally given the slip to the shadowing British ships.

Admiral Luetjens realized this now. That enemy craft were still looking for him and might not be far off, he of course knew. But give him another few hours—until darkness of that day of May 26. Then during the ensuing night he would arrive well within the protective cover of the famed Luftwaffe bombers and the U-boats. The German Fleet Commander, though by nature rather pessimistic, could not help but believe that he had a fairly good chance of escaping British detection during the rest of the daylight hours. The low clouds, the thick mist, the heavy seas would help cover him until night fell. Then the danger would be all but over. By daylight of May 27 he would be in safe waters.

His hopes were very shortly to be dashed.

***

At 7:00

A.M.

on May 26 the

Ark Royal

sent out her dawn patrol. The scouting planes were to look for the German battle cruisers

Scharnhorst

and

Gneisenau

coming out of Brest and for any U-boats that might be near by. An hour and a half later ten Swordfish planes, minus their torpedoes, were brought up on the flight deck. At 8:35, after

the carrier had turned into the wind, they began to take off in search of the

Bismarck

.

The

Ark Royal

was still tossing in the rough seas. It was touch-and-go whether the pilots would be able to get their little biplanes off the deck without cracking up or plunging into the waves. Vice-Admiral Somerville on the bridge of the

Renown

watched anxiously through his binoculars as the Swordfish careened off the pitching deck. To his relief, all got off safely. The aircraft had fuel for a three-and-a-half-hour search.

There now began for the men on the British ships a long and nerve-wracking wait. Somerville had radioed all the vessels in the area that the vital aerial search, on which they believed all now depended, had begun.

The

King George V

was some 300 miles to the northwest of Somerville’s squadron, zigzagging southeast at 24 knots. On her port bow, but still out of sight, was the

Rodney

with three destroyers. Neither ship knew exactly where the other was because they had been observing radio silence. They calculated, however, that they were not far apart and sailing on pretty much the same course.

Both battleships took in Somerville’s signal that he had launched ten planes from the

Ark Royal

to search for the

Bismarck

in an area between the two British naval forces. Admiral Tovey aboard the

King George V

, Captain Dalrymple-Hamilton on the

Rodney

, Vice-Admiral Somerville on the

Renown

and Captain L. E. H. Maund, the determined skipper of the

Ark Royal

, counted the minutes and waited nervously for some word from the scouting planes.

These British commanders would have agreed with Admiral Luetjens on one thing. If the

Bismarck

could not be located this day then she was safe. A great German naval victory would have been completed. With the

Hood

unavenged the British would have suffered a complete defeat—in fact, a disaster.

Nine o’clock came. Nine-thirty. Ten. There was no news at all from the searching planes. Soon they would have to turn back to refuel.

Then at 10:30

A.M.

a British plane began transmitting a message by radio. Excited wireless operators on a dozen British ships began writing it down.

…ONE BATTLESHIP… SIGHTED… POSITION 49 30 NORTH… 21 50 WEST… STEERING 150 DEGREES [Roughly southeast by east]… SPEED… 20 KNOTS…

One battleship! Was it the

Bismarck

? Admirals and captains went quickly to their chart rooms and marked the given position on their maps. So far as they knew no British battleship was in the immediate vicinity. It must be the

Bismarck

!

The Bismarck Is Found Again

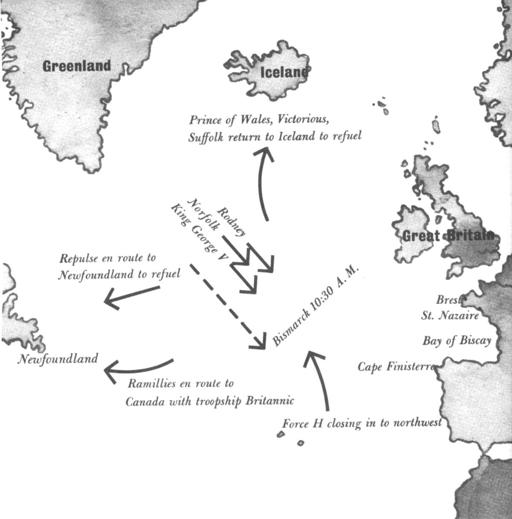

The situation at 10:30 A.M., May 26.

And what British aircraft had found her? The radio message did not come from any of the

Ark Royal

’s Swordfish planes. Instead the sender identified his plane as “Z/209.” That would be a Catalina—“Z” of the 209th Squadron, R.A.F. Coastal Command. It was one of the two flying boats which had been sent out that morning to make the long flight from Northern Ireland to the area of search.

It had been in the air over seven hours when, in the words of one of the pilots:

“George” [the automatic pilot] was flying the aircraft at 500 feet when we saw a warship. I was in the second pilot’s seat when the occupant of the seat beside me, an American, said: “What the devil’s that?”

I stared ahead and saw a dull black shape through the mist which curled above a very rough sea.

“Looks like a battleship,” he said.

I said: “Better get closer. Go round its stern.”

I thought it might be the

Bismarck

because I could see no destroyers round the ship and I should have seen them had she been a British warship.

Actually, as we know, the

King George V

no longer had any destroyers with her. If the pilot had happened to see the British ship, he undoubtedly would have made her out to be the

Bismarck

. But luck was with the British this day.

The pilot continued his report:

I left my seat, went to the wireless operator’s table, grabbed a piece of paper and began to write out a signal. The second pilot had taken over from “George” and gone up to 1,500 feet into broken cloud.

As we came round he must have slightly misjudged his position. Instead of coming up astern we found ourselves right over the ship in an open space between the clouds!

Two black puffs appeared outside the starboard wing tip. In a moment we were surrounded by black puffs. Stuff began to rattle against the

hull. Some of it went through and a lot more made dents in it.

I scribbled: “End of message.” and handed it to the wireless operator….

It was this message, crackling over the air waves, that electrified the officers and crew of every British warship engaged in the chase which up to this fateful moment had been so frustrating.

And the message had come from one of the two planes which had been sent out as a result of Air Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill’s hunch. The Z/209 had flown the southerly course of search on Sir Frederick’s gamble that the German battleship was steering first for Spain. And indeed the

Bismarck

’s position as reported at 10:30

A.M.

on May 26 showed that Admiral Luetjens had kept on a direct course not for Brest, as the Admiralty had predicted, but for Cape Finisterre. This was what Sir Frederick had felt certain of all along.

Acting on his hunch had paid off. After being lost for thirty-one and a half hours, the

Bismarck

had been found again!

Chapter Eight

The British Attack the Wrong Ship!

So intense was the

Bismarck

’s anti-aircraft fire that the Catalina quickly ducked into the clouds to escape being blown to pieces. When it came out again it could find no trace of the German battleship.

The

Bismarck

was again lost. But this time she was not lost for long. Half an hour later, one of the reconnaissance planes from the

Ark Royal

sighted her. The pilot mistook her for a cruiser and reported her as such to his carrier. The pilot of a second Swordfish arriving on the scene ten minutes later was sure the vessel was a battleship.

Which was it: a battleship or a cruiser, the

Bismarck

or the

Prinz Eugen

? On their return to

the carrier the fliers were closely questioned by Captain Maund. They were not quite sure which German ship they had seen. Identification in the murky weather was not easy. From a distance the two German war vessels looked very much alike. In fact, two days earlier Vice-Admiral Holland on the

Hood

had mistaken the

Prinz Eugen

for the

Bismarck

and directed his first salvos on her. If a veteran naval officer of high rank who had spent most of his life at sea found it almost impossible to distinguish the German cruiser from the battleship, it was not surprising that airmen had some difficulty.

Vice-Admiral Somerville on the

Renown

impatiently signaled over to the carrier for definite word. Captain Maund replied that his pilots were not sure which ship they had seen. They rather thought it was the

Prinz Eugen

. Somerville asked what Captain Maund himself thought. Maund replied that he was certain it was the

Bismarck

. What was his evidence? He had none. But like Air Marshal Bowhill he had a strong hunch. It too proved right.

Early that afternoon other planes from the

Ark

Royal

hovered over the phantom German warship and confirmed that it was the

Bismarck

.

Though the rediscovery of the

Bismarck

brought relief and joy to the British naval commanders, it also presented them with some serious problems.

Unfortunately the main British battleships, the

King George V

and the

Rodney

, were too far away from their intended prey. And they were the only ones which could engage the

Bismarck

in a gun battle. Admiral Tovey on the

King George V

calculated that the enemy ship had a lead on him of at least fifty miles if she steered directly for Brest. If the

Bismarck

veered southward toward the center of the Bay of Biscay, the lead was about 100 miles. Since the latter course was the one which would most quickly bring the German battleship within the cover of German shore-based bombers, she would very likely steer for it.

The problem that the British commander in chief faced was how to get at the

Bismarck

with his heavy guns before dawn the next day. By that time she would reach air cover from German bombers based on the French coast. He would

have to catch up with her before dark, or risk losing her again in the night. But this was obviously impossible at the slow rate he was gaining on her. Admiral Tovey saw that his only chance was to drastically reduce the

Bismarck

’s speed.

He had only two means of accomplishing this. Neither was very promising. One was by a destroyer torpedo attack. The other was by an assault from the torpedo-carrying Swordfish of the

Ark Royal

. Torpedoes, in fact, represented his only hope. But he was experienced enough to know that a ship built as stoutly as the

Bismarck

could probably withstand several torpedo hits without losing much speed.

Admiral Tovey, knowing his commanders as he did, had no doubt that Vice-Admiral Somerville would launch a torpedo attack from his carrier as soon as he could. No specific orders from the Commander in Chief would be needed to spur him on. And none were given. Nor were any orders given to the commander of a destroyer squadron which had now turned at full speed toward the reported position of the

Bismarck

.

This particular commander the Germans knew

well. And they did not like him. His name was Captain Philip Vian. On the night of February 16, 1940, he had taken his destroyer

Cossack

into a Norwegian fiord, boarded a German auxiliary supply ship, the

Altmark

, and liberated 300 British seamen who were being taken as prisoners of war to Germany. In the scuffle four Germans were killed and five wounded, with no British losses. The German navy was humiliated. Her admirals were furious. Captain Vian became their pet hate.

On the morning of May 24, when the

Hood

was sunk, Captain Vian had been well out to sea west of the British Isles. Still on his favorite

Cossack

he was in command of five destroyers escorting Troop Convoy WS8B. This was all the protection the precious convoy of 20,000 British troops had. The battle cruiser

Repulse

and the carrier

Victorious

, which originally were to have escorted it, had been detached to strengthen Admiral Tovey’s squadron.

On the 25th, as the Commander in Chief searched desperately for the lost

Bismarck

, he became aware that his battleships

King George V

and

Rodney

were in dire danger of U-boat

attacks because of their lack of destroyers. At 10:30 that night Admiral Tovey therefore sent an appeal to the Admiralty for an escort of these smaller ships.