The Sleeper in the Sands (7 page)

Painted in the corner, so far back in the shadows that I might easily have missed it, was the figure of a sun. But it was not in the style of the other frescoes: rather it had been painted roughly, as though in a great hurry, and had I not seen the same design before, I might never have recognised it. Yet as I stepped forward, I knew I was not mistaken: it was identical to the sun I had seen carved in the quarry, and below it were the same two squatting figures, and then a fine of Arabic script. Such resemblances, I knew, could not be mere coincidence; and it was with a shaking hand, and much excitement, that I reached for my pen to copy them out.

Once I had finished, I laid my drawing board aside and would have turned away, save that as I started to do so my torch caught something more, a touch of colour, very faint, upon the wall. I strained to inspect it more closely until I could just make out, beneath the rough strokes of the painted sun, the figure of a woman. As I studied it, and realised what it was, so again I felt a sudden shock. The portrait was clearly of a piece with the other artwork on the walls, for it had been painted in the familiar style of Akh-en-Aten’s reign; but, whether as a consequence of its obscure position or for some other reason, it had survived the fanatic zeal which had destroyed so much else within the tomb. Certainly, I thought, gazing upon the face of the woman, there was a quality which might well have served to hold a desecrator’s hand, for so great was her beauty, and so unsettling its nature, that it almost froze me to gaze upon it. Her head, impossibly massive upon a slender neck, seemed like a monstrous orchid swaying upon its stem; her black-rimmed stare was exalted and cold; her lips, half-formed between a smile and a frown, appeared to hint at deathly and unfathomable depths. Only these lips had retained their former brightness, for despite the passage of millennia they were still a fresh and vivid red - the same colour, I realised suddenly, as the graffito of the sun.

I had suspected at once whom the portrait portrayed. I bent down closer to search for a script, and found it, almost obliterated beneath a brush-stroke of red paint, by the side of the head. I had been learning the rudiments of hieroglyphics, and was able to trace, very haltingly, the syllables painted on the wall.

Nef-er-ti-ti.

I smiled to myself. So my supposition had been correct. ‘Nefer-titi’ -- ‘She-Who-Comes-In-Beauty’. Akh-en-Aten’s Queen.

There were more hieroglyphics running in a line down the wall. I permitted myself a second smile. Petrie, I knew, would be exceedingly intrigued, for Nefer-titi, like her husband, was a figure of great mystery, and I too, ever since my first glimpse of her carved upon the cliff, had found myself haunted by the image of the Queen. She had come in beauty -- so much her name had proclaimed; but almost nothing else about Nefer-titi was known. Although it had been the infallible custom for a Pharaoh to take his own sister as Queen, Akh-en-Aten as ever had trampled on tradition. Who Nefer-titi really was, and where she had come from, were questions still unanswered. Certainly, she had not belonged to Egypt’s royal line. Petrie, I knew, had his own ideas -- but there was a sorry lack of proof. I reached once again for my drawing board. I could not read the hieroglyphs, but if I copied them, Petrie would be able to. Who knew what information they might not prove to contain?

Who indeed? Even as I sit here almost thirty years later, in the afternoon warmth of the Theban sun, such a question must serve to chill me still. I am not, I think, by nature an over-imaginative man, and let me state, in mitigation of my youthful folly, that it taught me a lesson I have always remembered. It is all too easy for an archaeologist, eager in the pursuit of knowledge, to forget that a tomb is something more than a mere repository of historical details. It is also a place where the dead have been laid; and although, of course, I have no time for such fancies as ghosts, it is possible all the same for the dead to surprise those who would ignore them altogether.

Certainly, I was taught so that day. For I imagined, in the darkness of the tomb as I gazed at the face of Nefer-titi, that I saw her smile start to broaden, and her eyes to gleam; and I felt such a horror that I was paralysed. I thought suddenly how I had never seen a look so terrible; and even as I imagined that she was coming alive, so also I knew she was not human at all but something alien, and monstrous, and terribly dangerous. Of course I recognised, even as I conceived this, that such a fantasy was nonsense, and I forced myself to turn and rub my eyes. When I gazed upon the portrait of the Queen once again, all was as before, save that in the light of the torch her lips seemed somehow fuller than before. Intrigued despite myself, I brought the torch closer; yet even in the full glare of its beam, my hallucination persisted. So startled was I by this delusion, that I - God, but I blush even to set this down -- I bent down lower, as though to kiss the lips with my own, and reached out with my finger to touch the portrait’s cheeks. As I did so, the whole frieze seemed to shimmer before my gaze, like a true ghost indeed - a veil of infinite shimmering points, risen from the wall and hung upon the air. Then it collapsed and the image was gone, crumbled into a powder of fine dust upon the floor. Where the portrait had been there was only naked rock.

I never told Petrie. My sense of shame and guilt was too great. I sought instead, during the course of the following weeks, to make amends for my folly by uncovering something else -- some object of great beauty, perhaps, or historical worth; but alas, my efforts were to little purpose, and I found nothing to compare with the find I had destroyed. However, I did, towards the end of our excavations on the site, show Petrie my copies of the Arabic inscriptions. He was briefly intrigued by the image of the sun and its worshippers, but just as Newberry had done, he scoffed at the idea that an Arab might have copied the art of Akh-en-Aten’s reign. ‘Such a theory’ he told me, ‘although very original no doubt, has not the slightest foundation. Inspect the evidence more closely, Carter, and you will see how the idea must melt into air.’ Such a reproof was more painful than he could know, and so I pressed him no more. However, despite the brusqueness of Petrie’s rejection, I could not believe that the inscriptions were without significance at all -- and it amused me sometimes, in my more extravagant moments, to believe them a mystery of great significance indeed.

Two late discoveries in particular encouraged me to persist with this view. The first was the translation of the two lines of Arabic, which I had initially feared to be without meaning at all. Petrie himself, although reasonably versed in the language, had been unable to make sense of the copies I had made, and when he approached one of the nearby village elders and showed the two lines of Arabic to him, the old man had frowned and shrugged his shoulders. Such a disappointment might have seemed decisive -- save that I had observed how, when the old man had first gazed upon the lines, he had appeared to start and his face had grown pale. The next day, while Petrie was away elsewhere upon the site, I approached his foreman, and asked him if he could translate the two lines for me. The foreman, who spoke tolerable English, agreed willingly enough; but the moment he inspected them, he too grew pale and began to shake his head. But he could not, as the village elder had done, deny to me that he recognised the lines, and so I was determined to know what their meaning might be.

“Very bad,’ the foreman stammered. ‘Very bad indeed. Not good to know.’

‘Why not?’ I asked, growing more and more intrigued.

The foreman gazed about him as though searching for help, but none was forthcoming, and so he shook his head once more and breathed in deeply. ‘This,’ he whispered, ‘this is a curse.’ He pointed to the line I had copied from the quarry. ‘The curse of Allah. “Leave forever,” it says. “You are damned. You are accursed.” So it is written in the Holy Koran.’

‘And who is the object of Allah’s curse?’

Now the foreman began visibly to shake. ‘Iblis,’ he stammered. ‘Iblis, the Evil One, the angel who fell. And so, you see, please, sir -- it is not good to know.’

I ignored his plea and pointed to the second line. ‘And this one?’ I asked him. ‘Is this one too from the Holy Koran?’

The foreman’s nervousness now was almost painful to behold. He muttered something softly, then moaned and shook his head.

‘I am sorry,’ I pressed him. ‘I did not quite catch that.’

‘No,’ he whispered. ‘It is a very wicked verse. Not a verse from the Holy Koran at all. The Holy Koran was written by Allah. But this’ - he pointed -- ‘it was written by Iblis . . . written to deceive.’

What does it mean?’

Again he shook his head, but with the assistance of a considerable financial inducement, I was able to help him to overcome his qualms. He took the sheet of paper, and in a ghastly whisper he traced the meaning of the script. ‘“Have you thought upon Lilat,” he read, “the great one, the other? She is much to be feared. Truly, Lilat is great amongst gods.” ‘

He stared at me wide-eyed. ‘That is what it says.’

‘Who is Lilat?’

The foreman shrugged.

‘You must know.’

‘It is forbidden to know’

I tried to offer him more money, but this time he would not accept it, and again he shook his head. ‘Truly,’ he protested, ‘I do not know. A great demon -- much to be feared -- but otherwise, sir . . . truly -- I cannot say. I am sorry, sir.

I cannot say.’

I believed him; and indeed, hearing his talk of demons, I was suddenly gripped by a sense of the ridiculousness of it all. I dismissed the foreman and, left alone, smiled ruefully at the thought of how my careful investigations, pursued with such hope and with such high ambitions, had led me into nothing but a morass of superstition. Iblis! Lilat! Verses from the Koran! What had I to do with such mumbo-jumbo? The very thought of it served to fill me with shame. I returned to my excavations; and as I resumed the hard work of sifting fragments from the sands, I vowed to banish all wild conjectures from my mind for ever.

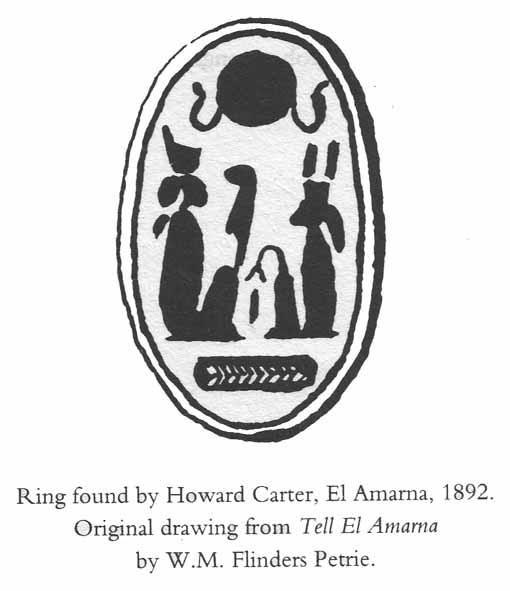

I stayed true to this resolution for the next few weeks -- and indeed, would willingly have continued to do so had I not made, in the final days of our excavations at El-Amarna, a second and far more startling find. I say it was I who made the find -- but that is not strictly true, for as summer came on and the temperatures rose, so also I began to suffer from the heat and then to grow quite ill. It was while I was seeking to recuperate one midday beneath the shelter of some palm trees that a workman came to me. He held out his hand and I saw, gleaming upon his palm, a beautiful golden ring. I took it with no especial show of enthusiasm, for I was still feeling faint, when suddenly, gazing upon it, all my strength was restored. I inspected the design on the ring with disbelief, rubbed my eyes, then inspected it again. Yet there could be no mistake -- I had recognised it at once: two figures crouching beneath the disk of the sun. I paid the workman, then hurried to my tent. I drew out my papers, and found the copies I had made of the two Arabic designs. I compared them with the ring. I breathed in deeply . . . they were the same in every way.

I returned to search out the workman. He led me to where he had made the discovery and I realised, inspecting the stratum of rubble, that the ring was certainly an artefact from the age of Akh-en-Aten, for it had been found amidst brickwork and shards of pottery all dateable to Akh-en-Aten’s reign. Yet despite the evidence before my own eyes, I could still barely credit it, even less explain what it appeared to suggest. For how

could

the designs - separated in time by more than two thousand years -- be so clearly identical? Was it just a coincidence? Or maybe, somehow, something more? I had no way of answering these questions -- yet at least I could now be certain that they needed to be asked.

Not at El-Amarna, though, for soon after the excavation was brought to a close, and with the end of the season I left the site for good. What I had learnt there, however, was to alter the entire course of my life. Under Petrie’s supervision, I had begun my transformation into an archaeologist, a true professional, able to dig and examine systematically, and to temper the wildness of my untutored enthusiasms. But I had also, so I thought, stumbled upon the evidence of a remarkable and puzzling enigma - one which was to haunt me, as it proved, for the length of my career.

After leaving El-Amarna, I was fortunate, in the autumn of 1893, to obtain a post which kept alive my concern with the mystery. Indeed, I was fortunate to obtain a post at all, for I had briefly feared that I would be left unemployed and with no alternative but to depart Egypt altogether. However, with the assistance and recommendation of my former patrons, I was able not only to continue at work in the country, but to do so in that part of it I had most desired to visit. Ever since Petrie had spoken to me of its magnificence, I had longed to behold the great temple of Karnak and to inspect the environs of ancient Thebes. The post I had obtained gave me just such a chance - and brought me to that place where I sit writing even now.

Nor, despite the many years I have spent here, has it ever ceased to excite my wonder. For it is the spot, perhaps, more than any in Egypt, where past and present can seem most annihilated; even the Nile, the palms, the very crops in the fields, when they are outlined by the brilliance of the midday sun can appear like the features of a timeless architecture, unchanging, unchangeable, so distinct and stilled they seem. I can remember being struck by this thought on my very first arrival at Thebes, leaning from the window of my train and then, a moment later, seeing a flash of stone above the distant palms, stone and yet more stone, and knowing that I was glimpsing the great temple of Karnak. I visited it that same afternoon and imagined, lost amidst its stupendous and grandiloquent bulk, that the centuries might indeed have learned to dread such a monument. Courtyard after courtyard, pylon after pylon, the temple appeared to extend without end, and I could not help but contrast it with the sands and barren waste of El-Amarna 200 miles away to the north. Certainly, I felt the mystery of Akh-en-Aten’s revolution all the more keenly now, for I could understand, gazing about me, that in seeking the destruction of Karnak, he had been attempting what Time itself is yet to achieve. What dreams could have inspired him to challenge so awesome a place? What dreams, what hopes -- or, it may have been, what fears?