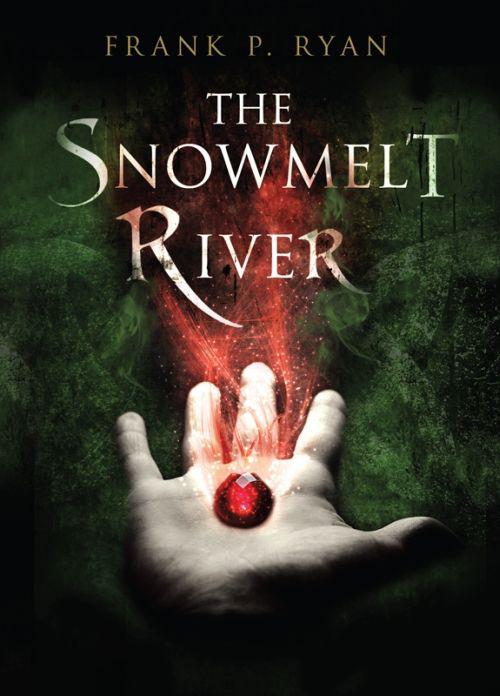

The Snowmelt River (The Three Powers)

The Snowmelt River

The Snowmelt River

Frank P. Ryan

Jo Fletcher Books

An imprint of Quercus

New York • London

© 2012 by Frank P. Ryan

First published in the United States by Quercus in 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57

th

Street, 6

th

Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to [email protected].

e-ISBN: 978-1-62365-049-0

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Random House Publisher Services

c/o Random House, 1745 Broadway

New York, NY 10019

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, institutions, places, and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons—living or dead—events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

For William

It is rumored from sources older than history that once these were happy lands, fruitful and bounteous as any heart might desire. The Arinn were the masters then, a race of magicians of unparalleled knowledge—but that very knowledge rather than wisdom was their undoing. In their arrogance, they wrought a malengin wondrous beyond understanding, yet so perilous that even today few other than the very wise or the very foolish dare utter its name. In such folly lay the seeds of our tormented world . . .

Ussha De Danaan: Last High Architect of Ossierel

Contents

The Enchantment

Part II:

The First Power

Part III:

Ossierel

PART I

The Enchantment

The Kiss

It was a beautiful Sunday morning, early and quiet, before most people were awake. A special day, so special the fifteen-year-old boy astride his stationary bicycle felt overwhelmed by it. Lately he had often dreamed about this day and his dreams always led him here, to the tree-shadowed lane outside the twin gates that led into the Doctor’s House. Alan Duval’s excitement centered on a mountain now out of sight but looming ominously in his imagination. Slievenamon was the name of the mountain. Beyond the small Irish town of Clonmel, over its streets and the decaying ramparts of its medieval walls, the mountain soared, shrouded in legend, two thousand, three hundred and sixty-eight feet above the horizon. And now, on this special morning, the mountain beckoned, casting an enchantment on the air like a thickening

scent, intoxicating and heavy, so he couldn’t help but be drawn to it even though it chilled the blood in his veins.

The left half of the gates was opening in the high ivy-covered wall. He listened attentively but heard none of the usual creaking. They had oiled the hinges last night, in readiness. He saw the front wheel of her bike roll through, then the flash of her auburn hair like a warm red flame, and even as his heart began to leap, he saw the excitement in her eyes, which were the soft green of evening light on the meadow that sloped down onto the far side of the river.

Kathleen Shaunessy lived in the Doctor’s House with her uncle, Fergal, and his housekeeper, Bridey. Nobody called her Kathleen except her uncle. Everybody else called her Kate.

Alan held her bike while she closed the half gate. Fourteen years old—she wouldn’t be fifteen until November 6—Kate wore blue jeans, tight-fitting overworn sneakers, and her upper body was hidden under a thick white sweater. This early in the morning, even at the close of a particularly hot summer, it would be cold. Over one shoulder she carried a denim backpack, just as he carried one on his back: a change of underwear, toothbrush and toothpaste, sandwiches and fruit. All they needed for a brief adventure.

“What did you tell Bridey?”

“I left her a note. Sure, she won’t believe the half of it anyway!”

She spoke with the soft singsong accent that had so bemused the American youth when he had first arrived

in Clonmel, an accent that in Kate he had come to love. Kate was so excited by the mission she didn’t appear to notice his own shakiness. He knew she had crept out through the first-floor bathroom window and climbed down the fall pipe with its convenient bends, as she had many a time before, because if she had left by the door her dog, Darkie, would have barked Bridey awake. He had no need to make furtive arrangements back at the sawmill since his grandad, Padraig, knew all about it. Padraig had helped them plan it. But Alan had worried about it all the same, tossing and turning through the night, with his bedroom window open to the cool night air, fitfully sleepless, as his puffy face now testified, and struggling to come to terms with his own fears.

He said, “Let’s check out the others. See if they’re ready!”

Kate switched on her cell phone, sending the text message:

RedyRNot

The answer flashed to her screen within moments, and with a shaking hand she held it out for Alan to see:

WotDyuTnkRevoltinGrl

Only Mark could have thought it through so quickly. Revolting had more than one meaning. It was typical of Mark’s sarcastic sense of humor.

So it was really happening. The excitement no longer bearable, Alan did something he had never done before, something at once shocking and wonderful: he hugged Kate across the bikes. Then he kissed her on the lips, feeling lost and weightless with the ecstasy of the contact, the quickness of her surprise. He could not have moved a muscle again until Kate, with the same blossoming of friendship into love, kissed him back there in the shadowed lane, the bicycles interlocking like a promise between them.

Now, his heart racing with the thrill of her response, he saw the flush invade her face, an expanding tide about the roots of her auburn curls and down into her throat above her sweater, with its monogram opening letter from the

Book of Kells

.

Wordlessly, they wheeled the bikes around so they faced the town. The road was empty and they cycled side by side, Alan’s jittery legs moving around in their own automatic motion, to the crossroads, with the slaughterhouse on the corner and the memory of animals bellowing in the trucks as they trundled in through the gates and the river tributary soon turning red with their blood. They wheeled right around the corner, picking up speed as they crossed over the first of the old stone bridges and then slowing momentarily at the second bridge, with the steps leading down to the river. With every turn of the pedals, the Comeragh Mountains loomed closer, their patchwork of green and yellow fields studded with whitewashed farm cottages,

and below them, extending southward and westward, the forests that fed Padraig’s sawmill. They rode on into the sunrise in silence. All of a sudden, time was running away with them. And there was the scary feeling that it might never slow back to normal again.

The Swans

It had begun only a few months earlier, although now it seemed more like years. Alan had been fishing the River Suir upstream of some small islands opposite the big fork in the river. The morning was misty and cool, and the water meadow, which the locals called the Green, was overgrown with grasses and rushes way higher than his knees. People said it was unusual. The plants were running wild that summer. The drier parts up close to the riverbank were dense with meadowsweet, floating over the ground in thick clouds and filling his nostrils with its sweet scent. In his hands was the old bamboo three-piece he had borrowed from his grandfather. He wasn’t expecting to get a bite. Just looking for some space away from the bustle of the sawmill—and away from Padraig’s intrusive fussing.

He hadn’t gotten any closer to finding answers since arriving in Clonmel two months earlier. If anything, the despair had relentlessly increased. It was there right now, as it was during every waking moment. Like the fire had gone out at the heart of him.

He had done his best to get it together. But he had nothing in common with the other kids here. He’d enrolled at the local high school thinking maybe he could connect with them through sports. He had always been pretty good at games. But even the games they played here were very different from back home. There was no football, no baseball, no basketball, nothing. Soccer here was Gaelic football, where, as far as he could make out, they just slugged the daylights out of one another. That or the hurling, which was an inexplicable combination of field hockey and lacrosse and if anything, even more violent. He must have looked half-crazy to the other kids at times, his thoughts going blank on him, just standing there in the playground or sitting at his desk, his eyes staring, his limbs suddenly weighted down, like he was wearing lead. He just couldn’t get his mind around the fact that Mom and Dad were gone, really gone, gone for good—period. How did you make sense out of something that couldn’t possibly make any sense? With their loss came a great anger. He wanted to know why they had died. There had to be a reason—somebody who was responsible. He must have drifted into another of his blank spells, his eyes wide open

but seeing nothing, when, abruptly, he came to with a sense of danger. There was a

homp-homp

noise from somewhere nearby, something strange cutting through the dreamy morning. And whatever it was, it was heading his way.

Then he saw the swans.

He had noticed their nest, with three huge eggs in it, on one of the small reedy islands that dotted the shallows. Something, maybe the toss of his line, had made the birds panic. The

homp-homp

was the beating of their wings as they took off, still only half out of the water and rising into the air like two white avenging angels. He saw every detail highlighted as if in slow motion: the pounding wings, the prideful black knobs on the upraised orange bills, the eyes all-black. He could hear the power in those webbed feet as they battered the surface. For several moments, as they cleared the water just thirty feet from where he was standing, he was overwhelmed by a sense of paralysis. He did nothing at all to save himself. He just stood still, returning, stare for stare, the rage in those alien eyes.

He felt a sudden blow, but from an altogether different direction to what he expected. He offered no resistance to being dragged to the ground in a confusion of bodies, arms and legs, hearing the fishing rod splintering into pieces, only distantly aware that he had ended up on his back with somebody else on top of him.

“Holy blessed mother—are you out of your mind?”

A voice, hot in his ear. A girl’s voice!

He glimpsed a face, pallid as goat’s cheese in striking contrast to the furnace of auburn hair. Immediately above them the swans clattered over their ground-hugging figures. His ears were full of a low throaty hissing. And then they were gone.

Alan just lay there for a while, the wind knocked out of him.

She spoke again. “Did you hear the sound of them hissing?”

He swallowed.

She added, “They’re supposed to be mute!”

His neck felt stiff. He had to turn his head through a painful ninety degrees to look at his savior, who was now sitting up beside him. He sat up himself and saw they were both covered by the creamy petals of meadowsweet.

All of a sudden she laughed, staring after the swans, which were sweeping low over the gentle rise of the Green, clearing the hedge by inches at the top and continuing the slow ascent until they dwindled to specks against the mountains.

“I . . . I guess it was my fault. My fishing must have spooked them.”

But she wasn’t even listening to him. He heard her whisper, as if to herself, “Sure, it’s a sign.”

“A sign of what?”

“Like maybe they sensed something different about you.”

He didn’t know what to say to that.

Climbing to his shaky feet, he must have looked even more awkward and gangly than usual. Alan had topped six feet on his fifteenth birthday, two weeks earlier. He kind of hoped he would stop growing soon so he wouldn’t end up having to bend his neck to get through doors like his beanpole grandfather. He thought about helping her up but he wasn’t sure she’d like it. Instead he extended his hand to shake hers.

“Hi. I’m Alan.”

She slapped his hand away instead of shaking it. She hopped to her feet with a grin and said, “Kate Shaunessy!”

What had he done that was funny? There was an awkward silence. He could see in her eyes that she was sizing him up.

Man! He was useless at dealing with girls. And that made him feel even more awkward than ever. And now he was looking at her, very likely staring, and it was making her blush a bright scarlet. She whistled to a small black-and-white sheepdog, which came bounding up. She plucked at its coat, brushing it free of grass stalks and petals, like she was getting ready to leave.

He said, “Anyway, thanks for that . . .”

He saw her eyes flash, like she had made up her mind about something. “I’ve seen you out here before. Pretending to be fishing.”

“I never noticed you.”

“Why would you notice me? I’ve been watching you, moping around, feeling sorry for yourself.”

“I—I wasn’t feeling sorry for myself.”

“I already know who you are. I know you’re an orphan.”

He shook his head, slowly, not knowing what to say.

Then he saw how she was trembling. She had been freaked out too. She blurted out, “Oh, you needn’t get embarrassed. I’m an orphan too.”

He stared at her for a long moment, wordless. Then he began to pick up the broken pieces of his grandad’s rod, making the best he could of the tangle of line, so he could hold the bundle together in his right hand.

She walked about a dozen paces but then she stopped and patted the dog. He had the feeling she was waiting for him.

Alan decided he would catch up with them. He was thinking about what she had just told him:

I’m an orphan too.

The way she had said it, kind of defiantly. It made him hope that somehow you really did come to terms with the bad things, even if they never made any sense.

She said, “I’m taking Darkie home. You can come with me, if you want. I’d like to show you something.”

“Show me what?”

“Are you interested in herbs?”

“I’ve never thought much about them.”

“Hmph!”

The mist had melted away from the morning and he hadn’t even noticed it going. It felt like maybe a little

of it had invaded his senses. His mind was groggy and his limbs felt numb, so he hardly registered the grassy bank under his feet as they passed by the island with the swans’ eggs.

“Well I’m very interested. I’ve been learning about them. Teaching myself, really. With some help from Fergal.”

They abandoned the Green to enter the beaten dirt track that ran southward along the riverbank.

“Fergal?”

“Fergal’s my uncle. But he’s a zoologist and not a botanist.”

They continued to chat and to stroll, following the dirt track, limited on their left by the slow-flowing River Suir and to their right by the hoary limestone wall that separated the river from the Presentation Convent School.

“Here, Darkie!”

Kate cracked open the right half of the gates, ushered the dog through, and then waited for Alan to follow after it into a big, overgrown garden. They were within sight of a very strange-looking house.

A woman paused after emerging from a stonewall outbuilding to take stock of them. Alan guessed that she must be the housekeeper for Kate’s uncle, Fergal. She was about mid-sixties, stocky and aproned, with thick gray hair held back in a bun. Under one brawny arm she carried an enamel basin filled with newly washed bedding.

Kate said, “Oh, Bridey—this is Alan.”

“Gor! I know who he is! Don’t I see for meself Geraldine O’Brien looking back at me!”

Alan caught Kate’s whispered, “Sorry!” Geraldine O’Brien was his mother’s maiden name. Dad had called her Gee.

“You knew Mom?”

He didn’t know if his question embarrassed Bridey, or if she heard it at all. She was suddenly caught up with shaking her fist into the sky. “Them blessed yokes, with their perpetual thundering!”

Alan glanced up at a jet passing high overhead. The sound might, in a pinch, be described as a thundering, however faint and distant.

Kate said, “I’m showing Alan around the place. But you could tell him more about the house.”

“Sure he’s not interested in this old ruin.”

“Ma’am, I am interested.”

Bridey peered back at him with a look of suspicion. “And why is that now? Because it looks so contrary?”

He couldn’t help but smile at her choice of word for the house, which captured the look of it perfectly. “Is it Victorian?”

“It started off as Georgian, but they went through a fit of overhauling it during Victorian times.” Bridey talked into the air, as if half-bemusedly to herself. “That was the time when it got its name, the ‘Doctor’s House.’ The Doctor in this case being the medical superintendent of what in them days was known as ‘the madhouse.’”

Kate tugged at his arm to haul him away from Bridey’s reminiscences. “We’re going to take a look at the garden.”

“Ah, be off the pair o’ you! Leave me to feed Darkie! But mind you keep clear of them greenhouses. Sure that uncle of yours is as stubborn as the tide.”

Kate waited until Bridey and Darkie had disappeared through a side door into the house before explaining. “My grandmother died when Fergal and Daddy were young. Bridey became their nanny. Then when Daddy died at the mission in Africa, she blamed the planes.”

“She blamed the planes?”

“For taking him to Africa.”

Alan shook his head.

“She’s convinced the house is cursed.”

“Cursed?”

“By what went on—in the old asylum.”

He smiled. “You’ve got to admit it’s a weird-looking house!”

“All the time I was growing up here I thought I was living in the same world that Lewis Carroll wrote about.”

The original house must have been compact and square, with sash windows divided up into small Georgian panes. But somebody, maybe the Victorian asylum keeper, had inserted an octagonal tower on one corner. Alan was standing right outside it, looking up at a structure of wooden frames filled with small glass panes, capped by an amazing minaret-style tower that soared to a tiny flagpole bearing the Irish flag. On

the gable ends of the house he saw other additions, very likely arising out of the same fantastic imagination. Ornate canopies topped fussy bay windows and porticos surrounded the front and back doors. There were additional dormer windows on the roof adjacent to soaring chimneys. The surrounding gardens were a labyrinth of arbors for roses, honeysuckle and other colorful flowering plants, contributing to a sort of fairyland of scents and colors.

They kept going around to the back, taking a course that avoided some large greenhouses with peeling paintwork and several broken panes.

He murmured, “Looks to me like Bridey had a point!”

“It’s nothing that a bit of fixing wouldn’t make right. They were properly cared for when Grandad was alive. He was interested in plants, an amateur like me. But Fergal is too busy to take proper care of them. Bridey wants to knock them all down. She’s terrified something bad will happen to us here. But we’re the only Shaunessys left of the family and the grounds are full of old memories from when Daddy and Uncle Fergal were growing up. So Fergal can’t bring himself to do it.”

She led Alan along a neglected path, overgrown with elderberry and nettles, which brought them face to face with a tunnel big enough to drive a car through. When they stepped inside, it was dank and gloomy. A hesitant light hovered around the entrance, as if fearful to penetrate deeper.

“I used to hide here from Bridey when we played hide-and-seek. It cuts right under the main road. Then there are all sorts of secret carriageways and tunnels before it finally comes out in the grounds of the hospital.”

“This still leads to the asylum?”

Kate nodded. “It’s called a mental hospital now. Once I saw a picture of the old superintendent. He had huge sideburns and a beard like Father Christmas. The whole place was arranged so patients could never leave, even when they came to work out here in the gardens.”

“Creepy!”

Kate hooted with laughter at the expression on his face. “Some of the mental cases still try to escape this way. Oh, I know I shouldn’t call them that. There are times I feel crazier than any of them myself. But Bridey could tell you stories. Those poor souls, they wade out into the river until it comes up to their chins. Then they shriek to the nurses that they’ll drown themselves if anybody tries to come and save them.”

“Shee—it!”

She led him back to the house where they did a tour of the downstairs rooms. Bridey appeared with two glasses of orange juice. They carried their drinks into a study filled with collections of tropical insects mounted in frames.

“Your uncle works with insects?”

“He’s an entomologist at University College Cork. He’s off right now counting new species in the African jungle before they become extinct.” Then, with what

seemed like a clumsy abruptness, she just came right out with it and asked him how his parents had died.