The Song of Troy

Authors: Colleen McCullough

To read this book as the author intended – and for a fuller reading experience – turn on ‘publisher’s font’ in your text display options.

For my brother, Carl, who died in Crete

on September 5th, 1965, rescuing some

women from the sea.

Death can find nothing to expose in him

that is not beautiful.

Homer,

Iliad

22.73

click or touch to enlarge image

NARRATED BY

Priam

There never was a city like Troy. The young priest Kalchas, sent to Egyptian Thebes during his novitiate, came back unimpressed by the pyramids built along the west bank of the River of Life. Troy, he said, was more imposing, for it reared higher and its buildings housed the living, not the dead. But then, he added, there was an extenuating circumstance: the Egyptians owned inferior Gods. The Egyptians had moved their stones with mortal hands, whereas Troy’s mighty walls had been thrown up by our Gods themselves. Nor, Kalchas said, could flat Babylon compete, its height stunted by river mud, its walls like the work of children.

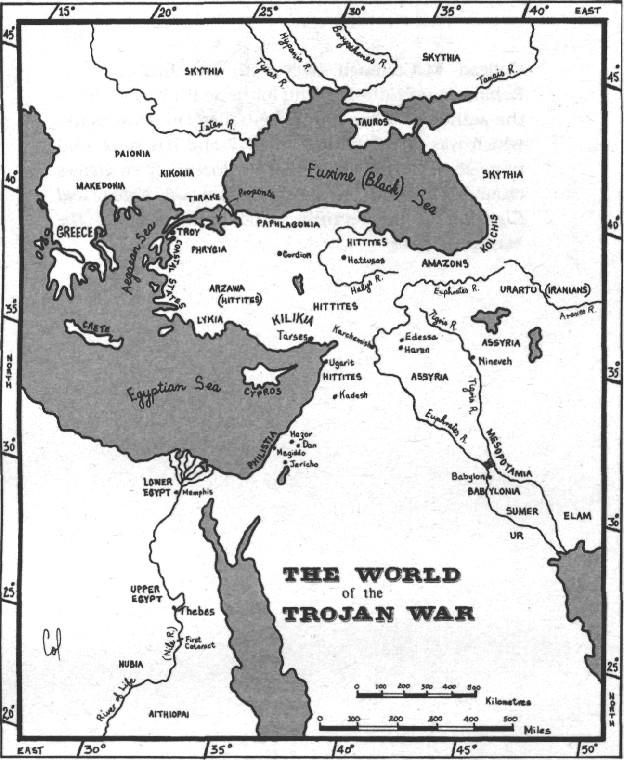

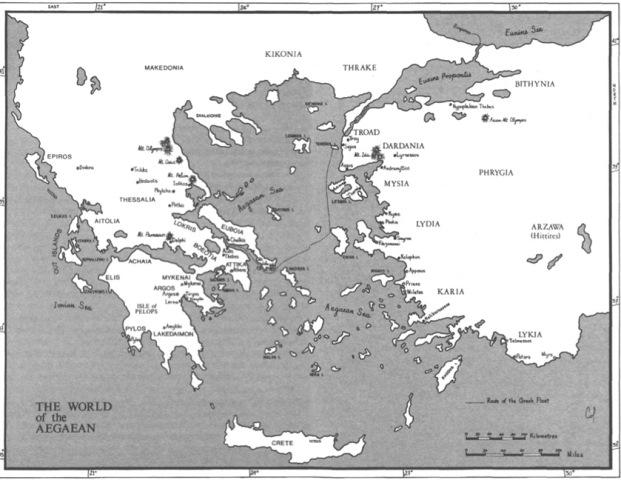

No man remembers when our walls had been built, it was so long ago, yet every man knows the story. Dardanos (a son of the King of our Gods, Zeus) took possession of the square peninsula of land at the very top of Asia Minor, where on the north side the Euxine Sea pours its waters down into the Aegaean Sea through the narrow strait of the Hellespont. This new kingdom Dardanos divided into two parts. He gave the southern section to his second son, who called his domain Dardania and set up his capital in the town of Lyrnessos. Though smaller, the northern section is much, much richer; with it goes the guardianship of the Hellespont and the right to levy taxes upon all the merchants who voyage in and out of the Euxine Sea. This section is called the Troad. Its capital, Troy, stands upon the hill called Troy.

Zeus loved his mortal son, so when Dardanos prayed to his divine father to gift Troy with indestructible walls, Zeus was delighted to grant his petition. Two of the Gods were out of favour at the time: Poseidon, Lord of the Sea, and Apollo, Lord of Light. They were ordered to proceed to Troy and build ramparts taller, thicker and stronger than any others. Not really a task for the delicate and fastidious Apollo, who elected to play his lyre rather than get dirty and sweaty – a way, he explained carefully to the gullible Poseidon, of helping to pass the time while the walls went up. So Poseidon piled stone upon stone while Apollo serenaded him.

Poseidon laboured for a price, the sum of one hundred talents of gold to be deposited each and every year thereafter in his temple at Lyrnessos. King Dardandos agreed; time out of mind the hundred talents of gold had been paid each and every year to the temple of Poseidon in Lyrnessos. But then, just as my father, Laomedon, ascended the Trojan throne, came an earthquake so devastating that it had felled the House of Minos in Crete and blown the island empire of Thera away. Our western wall crumbled and my father hired the Greek engineer, Aiakos, to rebuild it.

Aiakos did a good job, though the new wall he erected had neither the smoothness nor the beauty of the rest of that great, God-begotten encirclement.

The contract with Poseidon (I daresay Apollo hadn’t deigned to ask for a musician’s wages), said my father, was dishonoured. The walls had not proven indestructible after all. Therefore the hundred talents of gold paid each year to Poseidon’s temple in Lyrnessos would not be paid again. Ever. Superficially this argument looked a valid one, save that the Gods surely knew what even I, then a boy, knew: that King Laomedon was an incurable miser, and resented paying so much precious Trojan gold to a temple located in a rival city under the rule of a rival dynasty of blood relations.

Be that as it may, the gold ceased to be paid, and nothing happened for more years than it took me to grow from child to man.

Nor, when the lion came, did anyone think to connect his advent with insulted Gods or city walls.

To the south of Troy on the verdant plains lay my father’s horse farm, his one indulgence – though even indulgence had to bring profit to King Laomedon. Not long after Aiakos the Greek finished rebuilding the western wall, a man arrived in Troy from a place so far away we knew nothing of it beyond the fact that its mountains bolstered the sky and its grasses were sweeter than any other grasses. With him the refugee brought ten horses – three stallions and seven mares. They were horses the like of which we had never seen – large, fleet, graceful, long maned and long tailed, pretty faced, demure and tame. Splendid for drawing chariots! The moment the King set eyes on them, the man’s fate was inevitable. He died and his horses became the private property of the King of Troy. Who bred from them a line so famous that traders from all over the world came to buy mares and geldings; my father was too shrewd to sell a stallion.

Through the middle of the horse farm ran a worn and sinister track, once used by lions as they travelled north from Asia Minor to Skythia for the summer, and south again to winter in Karia and Lykia, where the sun retained the power to warm their tawny hides. Hunting had killed them off; the lion track became a path to water.

Six years ago the peasants had come running, pallid faced. I will never forget the sight of my father’s countenance when they told him that three of his best mares were lying dead and a stallion badly mutilated, the victims of a lion.

Laomedon was not the man to give way to unthinking rage. In a measured voice he ordered a whole detachment of the House Guard to station itself on the track the following spring, and kill the beast.

No ordinary lion, that one! Each spring and autumn he came through so stealthily no one saw him; and he killed far more than his belly needed. He killed for the love of it. Two years after his advent the House Guard caught him attacking a stallion. They advanced on him clashing their swords against their shields, intending to force him into a corner so they could use their spears. Instead, he reared to roar his war cry, charged straight at them, and went through their ranks like a boulder rushing downhill. As they scattered the kingly beast killed seven of them before going on his way unscathed.

One good thing came out of the disaster. A man torn by his claws lived to go to the priests, and told Kalchas that the lion bore the mark of Poseidon; on his pale flank was a black, three-pronged fish spear. Kalchas consulted the Oracle at once, then announced that the lion belonged to Poseidon. Woe the Trojan hand that struck at him! Kalchas cried, for he was a punishment visited upon Troy for cheating the Lord of the Seas of his annual hundred talents’ payment. Nor would he go away until it was resumed.

At first my father ignored Kalchas and the Oracle. In the autumn he ordered the House Guard out again to kill the beast. But he had underestimated the common man’s fear of the Gods: even when the King threatened his guardsmen with execution, they would not go. Furious but balked, he informed Kalchas that he refused to donate Trojan gold to Dardanian Lyrnessos – the priests had better think of an alternative. Kalchas went back to the Oracle, which announced in plain language that there

was

an alternative. If each spring and autumn six virgin maidens chosen by lot were chained in the horse pasture and left there for the lion, Poseidon would be satisfied – for the time being.