The Sorrows of Empire (34 page)

Read The Sorrows of Empire Online

Authors: Chalmers Johnson

Tags: #General, #Civil-Military Relations, #History, #United States, #Civil-Military Relations - United States, #United States - Military Policy, #United States - Politics and Government - 2001, #Military-Industrial Complex, #United States - Foreign Relations - 2001, #Official Secrets - United States, #21st Century, #Official Secrets, #Imperialism, #Military-Industrial Complex - United States, #Military, #Militarism, #International, #Intervention (International Law), #Law, #Militarism - United States

The Ford-Marcos agreement represented a slight improvement but the old problems still festered. Conditions around Clark Field and Subic Bay inflamed Filipino nationalism. The bases had given rise to a huge drug and sex industry employing thousands of poor Filipino women. Angeles City, home of Clark Field, was in the 1980s the most drug-afflicted city in the Philippines. Meanwhile, under martial law Marcos vastly expanded and politicized his own military establishment, appointing cronies who were personally loyal to him and giving the army unrestricted powers to arrest civilians. “Disappearances” and murders of anyone taking an interest in politics became common. Marcos also nationalized many manufacturing and business enterprises and gave them to his relatives. They proceeded to siphon off profits for their personal enrichment while the United States looked on with a blind eye.

In 1983, after three years in exile, the opposition politician Benigno Aquino returned to the Philippines to try to rally opposition to the Marcos regime. Minutes after landing at Manila airport on August 21, he was shot dead and his assassin, in turn, was shot and killed on the spot. Marcos claimed a Communist had been responsible for the murder, but a subsequent official commission of inquiry found that it was the work of a military conspiracy. Marcos rejected this finding and released the conspirators. Aquino’s widow, Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, became the leader of the opposition, as hundreds of thousands of people attended her husband’s funeral procession in Manila. It was the largest demonstration in the history of the Philippines and the beginning of a movement that would be dubbed “People Power.” Filipino People Power was never as explicitly anti-American as the Iranian version against the Shah or the Papandreou campaign against the Greek junta, but the presence of our bases and Washington’s blatant support for Marcos certainly helped mobilize the public.

In late 1985, in an attempt to acquire greater legitimacy and ensure continued American support, Marcos announced that a presidential

election would be held in February 1986. Corazon Aquino declared her candidacy. After the balloting, the Catholic Church, in the person of Cardinal Jaime Sin, denounced Marcos for widespread voter fraud and intimidation and challenged his claim to victory. The Reagan administration agonized over its friend’s difficulties and vacillated about recognizing the validity of Corazon Aquino’s election. In the meantime, in the face of continuous street demonstrations against Marcos, the Philippine armed forces abandoned him, either supporting the Aquino forces or refusing to act when ordered to fire on unarmed protesters.

31

On February 25, 1986, after over twenty years in power, Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos fled Malacañang Palace for Clark Air Force Base and then exile in the United States. When he arrived in Hawaii, Marcos was reportedly carrying suitcases containing jewels, gold bars, and certificates for billions of dollars’ worth of gold bullion. Aquino’s successor government estimated that Marcos had stashed away at least $3 billion in Swiss bank accounts, but some analysts put the figure as high as $35 billion. None of this money was ever recovered. Marcos died in Honolulu on September 28, 1989.

On February 2, 1987, the Filipino public overwhelmingly ratified a new national constitution. Its article 2, entitled “Declaration of Principles and State Policies,” started a process that led to the termination of the bases agreement with the United States. Sections 2 and 3 read as follows: “The Philippines renounces war as an instrument of national policy, adopts the generally accepted principles of international law as part of the law of the land and adheres to the policy of peace, equality, justice, freedom, cooperation, and amity with all nations. Civilian authority is, at all times, supreme over the military. The armed forces of the Philippines is the protector of the people and the State. Its goal is to secure the sovereignty of the State and the integrity of the national territory.” All Filipinos believed the United States kept atomic weapons ready for use at Subic and Clark. Section 8 of the state policies was the death knell for the bases: “The Philippines, consistent with the national interest, adopts and pursues a policy of freedom from nuclear weapons in its territory.” On June 6, 1988, by a vote of nineteen yes, three no, and one abstention, the Philippine Senate passed the Freedom from Nuclear Weapons Act, implementing

the constitutional mandate. The government of the Philippines now had something serious to talk about when the leases on the bases expired in 1991.

Totally misreading the post-Marcos political climate, the American negotiators badly bungled their attempt to extend the base leases. According to Roland G. Simbulan of the University of the Philippines, an adviser to the Philippine Senate, the United States “tried to bully its way through. Former Health Secretary Alfredo Bengzon, who served as vice chairman of the Philippine negotiating panel, later confirmed in a published article the ‘narrow and arrogant mindset of the U.S. negotiators, led by [Richard] Armitage during the negotiations. They tried to force a prolonged treaty of extension,’ Bengzon said.”

32

Armitage, President George H. W. Bush’s special representative for the Philippine military bases agreement, was a former CIA official. (He would later become deputy secretary of state in the Bush Junior administration.)

The Americans believed that the Filipinos were too poor to evict them and that conservatives in the Philippine Senate would support them. However, after Mount Pinatubo destroyed Clark air base, the United States cut its offer of assistance to the Philippines from about $700 million to $203 million; and on September 16, 1991, irritated by America’s tight-fistedness and its refusal to undertake a cleanup of the pollution at Clark Field, the Philippine Senate, by a vote of twelve to eleven, rejected the proposed renewal of the 1947 bases agreement.

33

Although the event was barely noted in the United States, all its military forces were completely withdrawn by November 24, 1992.

Since its expulsion, the United States has tried various stratagems to reintroduce its forces into the Philippines, always offering much-needed hard currency as an inducement. Early in 2002, we sent about a thousand Special Forces and supporting troops to help Filipinos fight the Abu Sayyaf, a Muslim “terrorist gang” on the southern island of Basilan with a record of kidnapping and extortion but not of political terrorism.

34

The main U.S. goal in the Philippines has been to negotiate a “Mutual Logistics Support Agreement” that would allow us access to Philippine bases for refueling, reprovisioning, and repairing ships without a case-by-case debate. On August 3,2002, in Manila, Secretary of State Colin Powell said

that “the United States is not interested in returning to the Philippines with bases or a permanent presence,” but it is unlikely that there was a single person in East Asia who believed him.

35

On February 20,2003, the Pentagon announced that it was sending a new contingent of nearly 2,000 troops to the Philippines in an operation against “terrorists” that “has no fixed deadline.”

36

ROM

W

AR TO

I

MPERIALISM

As the American empire grows, we go to war significantly more frequently than we did before and during the Cold War. Wars, in turn, promote the growth of the military and are a great advertising medium for the power and effectiveness of our weapons—and the companies that make them, which can then more easily peddle them to others. According to the journalist William Greider, “The U.S. volume [of arms sales] represents 44 percent of the global market, more than double America’s market share in 1990 when the Soviet Union was the leading exporter of arms.”

37

As the military-industrial complex gets ever fatter, with more overcapacity, it must be “fed” ever more often. The creation of new bases requires more new bases to protect the ones already established, producing ever-tighter cycles of militarism, wars, arms sales, and base expansions.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, we began to wage at an accelerating rate wars whose publicly stated purposes were increasingly deceptive or unpersuasive. We were also ever more willing to go to war outside the framework of international law and in the face of worldwide popular opposition. These were de facto imperialist wars, defended by propaganda claims of humanitarian intervention, women’s liberation, the threat posed by unconventional weapons, or whatever current buzzword happened to occur to White House and Pentagon spokespersons. In each war we acquired major new military bases that in terms of location or scale were disproportionate to the military tasks required and that we retained and consolidated after the war. After the attacks of September 11,2001, we waged two wars, in Afghanistan and Iraq, and acquired fourteen new bases, in Eastern Europe, Iraq, the Persian Gulf, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. It was said that these wars were

a response to the terrorist attacks and would lessen our vulnerability to terrorism in the future. But it seems more likely that the new bases and other American targets of vulnerability will be subject to continued or increased terrorist strikes.

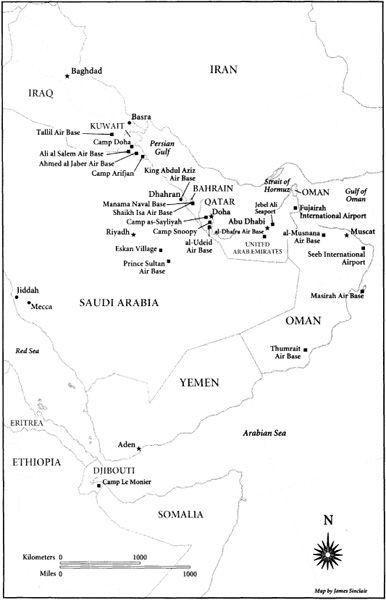

Following our usual practice, we established our bases in weak states, most of which have undemocratic and repressive governments. Immediately after our victory in the second Iraq war, we began to scale back our deployments in Germany, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, where we had become much more unpopular as a result of the war. Instead, we shifted our forces and garrisons to thinly populated, less demanding monarchies or autocracies/dictatorships, places like Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan.

38

A new picture of our empire has begun to emerge. We retain our centuries-old lock on Latin America and our close collaboration with the single-party government of Japan, although we are deeply disliked in Okinawa and South Korea, where the situation is increasingly volatile. Our lack of legitimacy in the war with Iraq has undercut our position in what Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld disparagingly called “the old Europe,” so we are trying to compensate by finding allies and building bases in the much poorer, still struggling ex-Communist countries of Eastern Europe. In the oil-rich area of southern Eurasia we are building outposts in Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia, in an attempt to bring the whole region under American hegemony. Iran alone, thus far, has been impervious to our efforts. We did not do any of these things to fight terrorism, liberate Iraq, trigger a domino effect for the democratization of the Middle East, or the other excuses proffered by our leaders. We did them, as I will show, because of oil, Israel, and domestic politics—and to fulfill our self-perceived destiny as a New Rome. The next chapter takes up American imperialism on the current battleground of global power, the Persian Gulf, a region where we have a long history.

PERSIAN GULF

IRAQ WARS

“From a marketing point of view,” said Andrew H. Card, Jr., the White House chief of staff on the rollout this week of the campaign for a war with Iraq, “you don’t introduce new products in August.”

New York Times,

September 7,2002

After all, this is the guy [Saddam Hussein] who tried to kill my dad.

P

RESIDENT

G

EORGE

W. B

USH,

at Houston, September 26,2002

The Persian Gulf, a 600-mile-long extension of the Indian Ocean, separates the Arabian Peninsula on the west from Iran on the east. At the head of the gulf is Iraq, whose access to the waterway is largely blocked by Kuwait. Along the gulf’s western coast, from Kuwait to Oman, lie what in the nineteenth century were known as the “trucial states,” tribal fiefdoms that then lived by piracy and with whom Britain signed “truces” that turned them into British protectorates. The British were chiefly interested in protecting the shipping routes to their empire in India and so were ready to trade promises from local tribal leaders to suppress piracy for British guarantees to defend them from their neighbors. In this way, Britain became the supervisor of all relations among the trucial states as well as all their relations with the world outside the Persian Gulf.

Prior to World War II, the gulf area was thus a focus for British imperialism. Only in Saudi Arabia did events take a different turn when, in May 1933, the Standard Oil Company of California obtained the right to drill in that country’s fabulously oil-rich eastern provinces. In return for a payment of 35,000 British pounds, Standard of California (SoCal),

known today as Chevron, obtained a sixty-year concession from King Ibn Saud to develop and export oil. Since British influence in the region was paramount, the Americans surely would not have gained a foothold had it not been for one of history’s most unusual figures, H. St. John Philby, Ibn Saud’s adviser and a specialist in Arabian matters. (He was also the father of Kim Philby, the British intelligence official who secretly went to work for the Soviet Union and became, after his defection to that country, the most notorious spy of the Cold War era.) Disturbed by the grossly imperialist practices of British oil companies in Iran, Philby persuaded King Ibn Saud to throw in his lot with the Americans. SoCal started oil production in Saudi Arabia in 1938. Shortly thereafter, the company and the monarchy formalized their partnership by creating a new entity, the Arabian-American Oil Company (Aramco), and brought in other partners—Texaco, Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon), and Socony-Vacuum (Mobil). Aramco has been described as “the largest and richest consortium in the history of commerce.”

1

Its corporate headquarters are still located at Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.