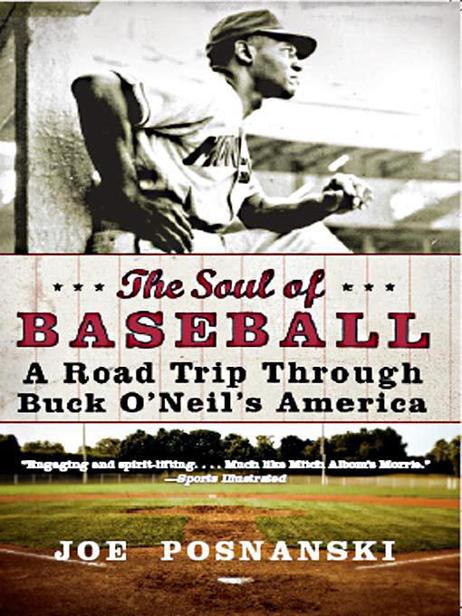

The Soul of Baseball

Read The Soul of Baseball Online

Authors: Joe Posnanski

A Road Trip Through

Buck O’Neil’s America

FOR MARGO

W

e were in Houston in springtime. We sat in a ballpark under a sun so hot the seats melted beneath us. There is something honest about Houston heat—it comes at you straight. It does not drain you like the Washington humidity or try and trick you like dry heat in Phoenix. In Houston, the heat punches you in the gut again and again. Buck O’Neil was wilting.

“I’m ready to go back to the hotel whenever you are,” Buck said to no one in particular, but mostly to me. We were at a ballgame. The baseball season had just begun. Before our road trip ended, Buck and I would go to many ballgames together. We would spend a full year, winter through winter, rushing to Buck’s next appearance, ballpark to hotel to autograph session to school to hotel to museum and back to ballpark—thirty thousand air miles and another few thousand more on the ground. We traveled around America. Buck talked about baseball.

In time, I would grow accustomed to Buck’s moods, his habits, his style, the way he wore his hat, the way he sipped his tea, the way he walked and talked, and the way he dressed. Buck splashed color. He wore bright crayon shades: royal purple, robin’s-egg blue, olive green, midnight blue, and lemon yellow. He wore pinstripe white suits, orange on orange, and shoes that perfectly matched the color of his pants. He never wore gray.

In time, I would grow accustomed to Buck’s boundless joy. That joy went with him everywhere. Every day, Buck hugged strangers, invented nicknames, told jokes, and shared stories. He sang out loud and danced happily. He threw baseballs to kids and asked adults to tell him about their parents, and he kept signing autographs long after his hand started to shake. I heard him leave an inspiring and heartfelt two-minute phone message for a person he had never met. I saw him take a child by the hand during a class, another child grabbed her hand, and another child grabbed his, until a human chain had formed, and together they curled and coiled between the desks of the classroom, a Chinese dragon dance, and they all laughed happily. I saw Buck pose for a thousand photographs with a thousand different people, and it never bothered him when the amateur photographer fumbled around, trying all at once to focus an automatic camera, frame the shot like Scorsese, and make the camera’s flash pop at two on a sunny afternoon. Buck kept his arm wrapped tight around the women standing next to him.

“Take your time,” he always said. “I like this.” Always.

“Man, it’s hot in Houston,” Buck said, and he launched into a story about one of his protégés, Ernie Banks, the most popular baseball player ever to take Wrigley Field on the North Side of Chicago. Banks played baseball with unbridled joy. They called him “Mr. Cub.” Funny thing, when Banks first signed with the Kansas City Monarchs—Banks was nineteen then, it was 1950—he was a shy kid from Texas. He sat in the back of the team bus and hardly spoke—“Shy beyond words,” Buck called him. Buck was the manager of that Monarchs team, and he would say to Banks, as he said to all his players, “Be alive, man! You gotta love this game to play it.”

Ernie Banks embraced those words. He opened up. His personality emerged. “I loved the game more,” he would say. Then he was drafted into the army. When Banks joined the Chicago Cubs three years later, he had become a new man. He ran the bases hard, he swung the bat with force, he banged long home runs, he dove in the dirt for ground balls. He smiled. He waved. He chattered. He played the game ecstatically. He was the first black man to play baseball for the Chicago Cubs, but his joy transcended color. In the daylight at Wrigley Field, Ernie’s joy brought him close to all the shirtless Chicago men who drank beer in the bleachers behind the ivy-covered walls. Ernie’s joy brought him close to the men and women who came to the ballgame to get away from the humdrum of daily life. Ernie’s joy brought him close to all the fathers and sons in the stands who dreamed of playing big-league ball. They dreamed of playing ball like Ernie Banks.

“I learned how to play the game from Buck O’Neil,” Banks would say. Buck said no, Ernie Banks knew how to play, but what he did learn was how to play the game with love. Banks began each baseball game by running up the dugout stairs, taking them two at a time. He then breathed in the humidity, scraped his cleats in the dirt, and shouted what would become his mantra: “It’s a beautiful day for a ballgame. Let’s play two.”

Buck remembered a July game Banks played in Houston. That was 1962 at old Colt Stadium. Buck O’Neil was a coach for the Cubs then, the first black coach in the Major Leagues. That Houston sun beat down hard on an afternoon doubleheader. Buck watched Banks run up the dugout steps, two at a time, he breathed in the humidity, he scraped his cleats in the dirt, and he said his bit—Beautiful day, let’s play two. Ernie Banks fainted before the second game. That’s Houston heat.

Buck was ninety-three years old. People often marveled about his age. Buck never turned down an invitation to speak, and he never said no to a charity, and he often appeared at three and four events a day. And it was amazing: Buck always seemed fresh and alive and young. Only those close to him understood that it was an illusion, that he worked hard to stay young. He took catnaps on the car rides between appearances. He ate two meals a day as he had for seventy-five years. He often showed up for an event, waved to the crowd, spoke for a few minutes, and then excused himself. “Where did Buck go?” people would ask. By the time they had noticed him missing, Buck had already collapsed in his hotel bed.

Something else invigorated him—something harder to describe. It was the thing I found myself chasing all through our road trip. That day in Houston, Buck had signed autographs and told stories and posed for photographs. By the time the ballgame started, he was already exhausted. By the second inning, the sun had beaten him down too. Buck announced that he was ready to go home. Then something small happened. The Houston right fielder, Jason Lane, tossed a baseball into the stands at the end of an inning. The ball landed a few rows down from where we were sitting. Two people reached for the ball. One was a thirty-something man in a sports coat and loosened tie. The other was a boy, probably ten or eleven. The boy wore a Houston Astros jersey with the number 7 on it. Buck always loved baseball numerology. Number 7 was particularly magical—it was Mickey Mantle’s number. In Houston, 7 belonged to Craig Biggio, a scrappy, hardworking player. Biggio was a Buck O’Neil kind of player.

The boy and the man both stretched for the ball, but the man was taller and he had the better angle. He caught the ball. He threw his arms up in the air, as if he was signaling a touchdown. He showed the ball to the people around him. He did some variation of the “I got the ball!” dance you see at ballparks. The man was happy. The boy was glum, and he sat down.

“What a jerk,” I said.

“What’s that?” Buck muttered.

“That guy down there caught the ball and won’t give it to a kid sitting right behind him.”

Buck looked down and—on cue—the man showed his new baseball to his neighbors. He talked at a feverish pace. Even though we were a few rows back and could not pick up on what he was saying, I had no doubt he was recounting his catch, and I had no doubt that the longer he talked, the more dazzling his catch would become. Everyone likes to believe they’re the hero of the story. In this guy’s mind, the story was not: “Hey, look at me, I’m the jerk who took this ball away from a kid.” No, in his revisionist history, he had to jump up to catch the ball. He had to stand on his chair. He had to catch the ball to save a baby. Maybe he had to dodge snakes and avoid rolling boulders. By the end of the game, I suspected, he would make his catch seem on par with the catch made by Al Gionfriddo, “the Little Italian,” who went back to the wall in the 1947 World Series and snagged a Joe DiMaggio smash, spurring the Great DiMaggio to kick the dirt in disgust. The man in the sports coat and loosened tie looked proud as he relived his heroics. One row back, the kid in the number 7 jersey moped while his father mussed his hair.

“What a jerk,” I said again.

“Don’t be so hard on him,” Buck mumbled. “He might have a kid of his own at home.”

That stopped me cold. A kid of his own. I had not thought of that. I looked hard at the man, who now wrapped his fingers across the seams of the baseball. He appeared to be showing his friends how to throw a curveball.

A kid of his own.

True, the man did not seem the father type. But it was possible. I tried to imagine this man’s kid sleeping at home—a little boy perhaps sleeping on Houston Astros bedsheets. I tried to imagine the boy’s thrill the next morning when he woke up, got out of bed, rubbed the sleep from his eyes, and then looked toward his dresser, and…what’s this? A baseball! White! Glowing!

Did you catch this for me, Dad?

You betcha. It was a one-handed grab! I had to dodge a snake! And later, if you finish your homework, we’ll go out and throw that ball around. I’ll teach you how to throw a curveball.

Would you, Dad? That would be so great!

I tried, as I would the whole road trip with Buck O’Neil, to see things through his eyes. For five seasons, I would watch Buck look at the bright side. He had every reason to feel cheated by life and time—he had been denied so many things, in and out of baseball, because of what he called “my beautiful tan.” Yet his optimism never failed him. Hope never left him. He always found good in people.

“Wait a minute,” I said to Buck. “If this jerk has a kid, why didn’t he bring the kid to the ballgame?”

Buck O’Neil smiled. He was not tired now. He looked young again.

“Maybe,” Buck said without hesitation, “his child is sick.”

And I realized that no matter how hard I tried, I would never beat Buck O’Neil at this game.