The Spanish Cave (12 page)

Authors: Geoffrey Household

“I don't mind,” said Dick. “And perhaps we could start a branch in England some time.”

Echegaray laughed.

“I'll send you to Southampton to learn some of their tricks of yacht building,” he said. “But that's beside the point. I'm glad you're willing, Ricardito, for I've set my heart on having you. I thought you might do, and took you with me in the boat to see how you'd behave in an emergency. You must forgive me for making you go through all those horrors. I didn't think it would be such a test as it was.”

“Forgive you?” exclaimed Dick. “I wouldn't have missed it for the world!”

“Well,” said Echegaray, “I'll see if I can get your brother's consent, and then we'll celebrate. Send a wire to Olazábal and tell him that he and his bunch of pirates are invited to dinner two weeks from to-day.”

“Two weeks from to-day!” Dick protested. “You won't be up.”

“I will!” said Echegaray, “and walking, too!”

Don Ramon kept his word. In two weeks he was just able to totter down to the quayside to greet the

Erreguiña

when she steamed up river with siren tooting and a string of flags flying, most of which had undoubtedly been cut from the tails of Olazábal's more colourful shirts.

The dinner was served in Hal's house, for it had been agreed that Paca must cook it, and Paca refused to work outside her own kitchen on so great an occasion. Don Ramon, for once wearing a tie, Doña Mariquita, and Hal sat at one end of the massive table; Dick, Lola, and Olazábal at the other. Pablo and the crew of the

Erreguiña

occupied the middle, with Father Juan amongst them to act as a restraining influence in case their flights of fancy became too profane. The postmaster, the innkeeper, and the Llanes doctor were thereâthe latter in a festive mood, for Echegaray had sworn that he knew just as much as the specialist, and had insisted on paying him the same fee. An empty place stood ready for Paca to slip into, as soon as she had passed the last course into the hands of her helpers.

When the main business of eating was over, and the champing of powerful jaws had given way to a roar of noise and laughter, Echegaray stood up.

“Condesa de Ribadasella,” he said, “Doña Mariquita,

and gentlemen! I dedicate this cup to the bravest act I ever heard of! And I've heard of some remarkable ones! To Ricardito's rescue ofâshall I say?âhis lady in distress!”

They drank. The room shook with the wild cheers of Olazábal's crew. There was no holding them. They looked prepared to go on expressing their admiration of Dick till midnight. Indeed, they would have done so, had they not become suddenly abashed by the presence of Doña Mariquita, and sat down instantly and in a body.

The unexpected collapse of the crew left Pablo still on his feet. He had been shouting a toast of his own, under cover of the general noise, and now found himself announcing in a dead silence:

“May he marry Lola, and be the Count of Ribadasella!”

Dick blushed purple. Pablo dropped into his seat and pretended he had lost his napkin under the table; it was, as a matter of fact, firmly tucked into his collar. Lola calmly grabbed Olazábal's glass, and drank the toast.

“I hope he does, Pablo,” she said. “I'll have him!”

“Lola!” exclaimed her scandalised motherâbut the next moment broke into a ripple of laughter, for she had caught Father Juan looking at the children with a holy and satisfied expression as if they were already before him at the altar.

“Time enough for that, young woman!” said Echegaray.

“And if you're both of the same mind ten years from now, I dare say there won't be so much difficulty as you think. My friends, Don Enrico, at my earnest request, has permitted me to take charge of Ricardito's education and future. It won't be a legal adoption, for I know that Ricardito doesn't want to change his nationality, and I don't expect him to. But he will be free to use my name as well as his own, and he will succeed me in everything. In everything,” he repeated, looking straight at Paca.

“I don't know,” began Father Juan, “that I altogether approve of this.”

“You will, padre, you will!” said Echegaray. “I'll give him an education such as no boy ever had! You suspect me, padre, of possessing certain unusual powers. For the sake of argument, let's admit I have them. But they are merely simple rules of thumb for getting results that are puzzling. I can't tell you why they get results, nor could my ancestors. But perhaps, some day, my new son

will

be able to tell you why, for besides those rules of thumb he's going to learn all the biology and physics that the best universities can teach him.”

“He'd be rather an alarming person to have in the family, Don Ramon,” said Doña Mariquita, smiling. “Will he have webbed feet and a laboratory too?”

“And let me ride on his porpoise?” added Pablo.

“And build me another

Erreguiña,

when this one is broken up?” asked Olazábal.

“He'll do anything you like,” said Hal, answering

Dick's appealing glance, “if you'll only talk about somebody else.”

“All right,” said Father Juan, “we will! I can see that you're all going to make speeches about Don Ramonâthat is, those of you who can stand upââ”

“I can stand up,” interrupted Pablo, and did so.

“Well, sit down,” said Father Juan. “But before you begin your speeches, I propose the health of the happiest person here, the one to whom we are all most grateful at the momentâPaca!”

“Ay, mi madre!”

exclaimed Paca, and would have fled to her kitchen, had not Dick jumped up, reined her in by her apron strings, and deposited two resounding kisses on her scarlet cheeks.

“A dance! A dance!” roared Olazábal.

He seized a guitar, put one foot on the table, and crashed into the mad melody of an ancient Basque war-song, while the seamen stamped back and forth in two swinging lines. Then Doña Mariquita took the guitar, and followed him with song after song from Old Castille, and little by little the whole village gathered in the courtyard to listen. And the party, led by Olazábal and Doña Mariquita, danced through the door to join them.

CHAPTER EIGHT

EPILOGUE

IT was a year ago that I went from Madrid to Bilbao to order one of the dreams of my lifeâa thirty-foot yawl built by my friend Ramon Echegaray. They told me at the yard that he was in some unheard-of village in Asturias, badly hurt by the explosion of a petrol tank. I could get no other information until one afternoon when the waiter at the Harbour Café telephoned me that Don Ramon had returned. I found him at his usual table, accompanied by an attractive boy who was introduced to me as Don Ricardo Echegaray Garland.

Echegaray had his right arm in a sling, and was pounding the table with his left.

“Fools!” he said. “Fools! They're all fools! Sit down,

amigo

!”

“Who are fools?” I asked.

“The admiralty. They say I'm crazy, that Olazábal and his crew were drunk, that Father Juan is suffering from senile decay, and that if we saw anything at all it was a seal!”

“Begin,” I suggested, “at the beginning.”

“I will,” said Echegaray.

And for two hours he held me spellbound with the story, occasionally turning to Dick for corroboration.

“Have you any idea what the beast was?” I asked when he had finished.

“I hardly saw it,” Echegaray said, “and so I can't tell. But I got together some pictures of extinct reptiles and asked Ricardito and the other four to pick the one that most resembled it. They all chose a creature called a plesiosaur.”

“It was bigger than any of the fossil plesiosaurs,” added Dick. “Because it was very old, I expect.”

“And what was the mess on its forehead?” I asked.

“According to my doctor,” answered Don Ramon, “it was a pineal eye, partly degenerated.”

“Well,” I said, “if you can get the skeletons of its ancestors out of the cave, you'll have proof enough for any admiralty.”

“We tried last week,” said Echegaray, “but we couldn't go more than a hundred feet beyond the rock. The explosions loosened the walls and roof of the channel, and at the next high tide they fell in. I've got half a dozen men searching the foothills right now for the entrance into the last caveâthe rift through which the sun fell on the blue algæ. When I've found it, there'll be headlines in all the papers on earth.”

“Meanwhile, do you mind if I write the story as fiction?”

“

Hombre!

Why not?” exclaimed Echegaray, surprised and pleased at the idea. “We'll drive over to Zumaya and have a talk to Olazábal, and then if you have time you could spend a week with Don Enrico at Villadonga and look over the ground.”

I didâand here is the story.

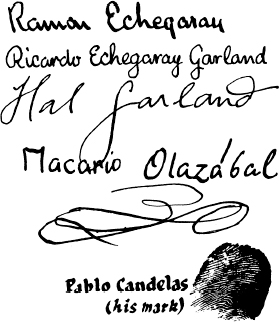

Por lo presente declaramos que los hechos más arriba contados por Don Godofredo Household, con excepción de lo que se ha suprimido por motivo de la discreción, son conformes a la verdad.

This is to certify that the facts as told above by Mr. Geoffrey Household conform to the truth, apart from such alterations as have been made for reasons of discretion.

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 1936, 2014 by Geoffrey Household

Cover design by Drew Padrutt

978-1-5040-1047-4

This edition published in 2015 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW ABOUT

FREE AND DISCOUNTED EBOOKS

NEW DEALS HATCH EVERY DAY