The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (35 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

In the past, when arguments about inequality centred on the privations of the poor and on what is fair, reducing inequality depended on coaxing or scaring the better-off into adopting a more altruistic attitude to the poor. But now we know that inequality affects so many outcomes, across so much of society, all that has changed. The transformation of our society is a project in which we all have a shared interest. Greater equality is the gateway to a society capable of improving the quality of life for all of us and an essential step in the development of a sustainable economic system.

It is often said that greater equality is impossible because people are not equal. But that is a confusion: equality does not mean being the same. People did not become the same when the principle of equality before the law was established. Nor – as is often claimed – does reducing material inequality mean lowering standards or levelling to a common mediocrity. Wealth, particularly inherited wealth, is a poor indicator of genuine merit – hence George Bernard Shaw’s assertion that: ‘Only where there is pecuniary equality can the distinction of merit stand out.’

359

, p. 71

Perhaps that makes Sweden a particularly suitable home for the system of Nobel prizes.

We see no indication that standards of intellectual, artistic or sporting achievement are lower in the more equal societies in our analyses. Indeed, making a large part of the population feel devalued can surely only lower standards. Although a baseball team is not a microcosm of society, a well-controlled study of over 1,600 players in twenty-nine teams over a nine-year period found that major league baseball teams with smaller income differences among players do significantly better than the more unequal ones.

360

And we saw in earlier chapters that more equal countries have higher overall levels of attainment in many different fields.

THE POLICY FAILURE

Politics was once seen as a way of improving people’s social and emotional wellbeing by changing their economic circumstances. But over the last few decades the bigger picture has been lost. People are now more likely to see psychosocial wellbeing as dependent on what can be done at the individual level, using cognitive behavioural therapy – one person at a time – or on providing support in early childhood, or on the reassertion of religious or ‘family’ values. However, it is now clear that income distribution provides policy makers with a way of improving the psychosocial wellbeing of whole populations. Politicians have an opportunity to do genuine good.

Attempts to deal with health and social problems through the provision of specialized services have proved expensive and, at best, only partially effective. Evaluations of even some of the most important services, such as police and medical care, suggest that they are not among the most powerful determinants of crime levels or standards of population health. Other services, such as social work or drug rehabilitation, exist to treat – or process – their various client groups, rather than to diminish the prevalence of social problems. On the occasions when government agencies do announce policies ostensibly aimed at prevention – at decreasing obesity, reducing health inequalities, or trying to cut rates of drug abuse – it usually looks more like a form of political window-dressing, a display of good intentions, intended to give the impression of a government actively getting to grips with problems. Sometimes, when policies will obviously fall very far short of their targets, you wonder whether even those who formulated them, or who write the official documents, ever really believed their proposals would have any measurable impact.

Take health inequalities, for example. For ten years Britain has had a government committed to narrowing the health gap between rich and poor. In an independent review of policy in different countries, a Dutch expert said Britain was ahead of other countries in implementing policies to reduce health inequalities.

361

However, health inequalities in Britain have shown little or no tendency to decline. It is as if advisers and researchers of all kinds knew, almost unconsciously, that realistic solutions cannot be given serious consideration.

Rather than reducing inequality itself, the initiatives aimed at tackling health or social problems are nearly always attempts to break the links between socio-economic disadvantage and the problems it produces. The unstated hope is that people – particularly the poor – can carry on in the same circumstances, but will somehow no longer succumb to mental illness, teenage pregnancy, educational failure, obesity or drugs.

Every problem is seen as needing its own solution – unrelated to others. People are encouraged to take exercise, not to have unprotected sex, to say no to drugs, to try to relax, to sort out their work–life balance, and to give their children ‘quality’ time. The only thing that many of these policies do have in common is that they often seem to be based on the belief that the poor need to be taught to be more sensible. The glaringly obvious fact that these problems have common roots in inequality and relative deprivation disappears from view.

TRENDS IN INEQUALITY

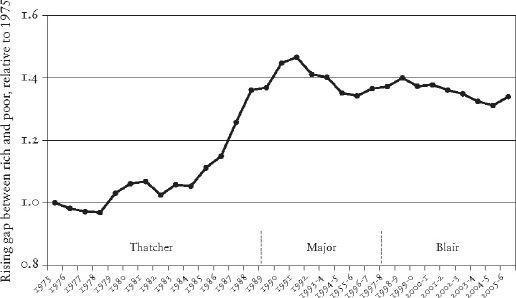

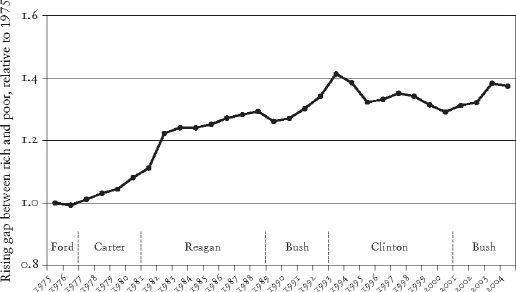

Inequality has risen in many, but not all, developed countries over the last few decades. Figures 16.1 and 16.2 show the widening gap between the incomes of rich and poor in Britain and the United States over a thirty-year period. The figures show the widening gap between the top and bottom 10 per cent in each country. Both countries experienced very dramatic rises in inequality which peaked in the early 1990s and have changed rather little since then. In both countries inequality remains at levels almost unprecedented since records began – certainly higher than it has been for several generations. Few other developed countries have shown quite such dramatic increases in inequality over this period, but only a very few – such as Denmark – seem to have avoided them entirely. Others, like Sweden, which avoided them initially, have had steep rises since the early 1990s.

Figure 16.1

The widening gap between the incomes of the richest and poorest 10 per cent in Britain 1975 (=1) to 2005–2006.

Figure 16.2

The widening gap between the incomes of the richest and poorest 10 per cent in the USA 1975 (=1) to 2004.

The figures showing widening income inequality in Britain and the United States leave no room for doubt that income differences do change substantially over time and that they are now not far short of 40 per cent greater than they were in the mid-1970s.

If things can change so rapidly, then there are good reasons to feel confident that we

can

create a society in which the real quality of life and of human relationships is far higher than it is now. But rather than change just happening, we must be constantly looking for the opportunities it presents to take another step towards a more inclusive society. We have already seen how the development of a sustainable economy lends itself to egalitarian policies. In the rest of this chapter we will move on, first to discuss ways of overcoming the democratic deficit in economic institutions which protects inequality, enforces hierarchy and damages our experience of work, and then to suggest ways in which current trends in technological change may help create the basis of a new kind of economy consistent with the development of happier and more egalitarian societies. But these are merely suggestions as to how our societies might be developed. Readers will have others of their own, and will no doubt see weaknesses in ours.

DIFFERENT ROUTES TO GREATER EQUALITY

Rather than suggesting a particular route or set of policies to narrow income differences, it is probably better to point out that there are many different ways of reaching the same destination. In Chapter 13 we showed that although the more equal countries often get their greater equality through redistributive taxes and benefits and through a large welfare state, countries like Japan manage to achieve low levels of inequality

before

taxes and benefits. Japanese differences in gross earnings (before taxes and benefits) are smaller, so there is less need for large-scale redistribution. This is how Japan manages to be so much more equal than the US, even though its social security transfers were a smaller proportion of GDP than social security transfers in the USA.

362

Although, of all the countries included in our analyses, the USA and Japan are at opposite extremes in terms of inequality, the proportion of their GDP taken up by government social expenditure is small in both cases: they come second and third lowest of the countries in our analysis.

Similar evidence that there are very different routes to greater equality can also be seen among the American states.

363

The total tax burden in each state as a percentage of income is completely unrelated to inequality. Because Vermont and New Hampshire are neighbouring New England states, the contrast between them is particularly striking. Vermont has the highest tax burden of any state of the union, while New Hampshire has the second lowest – beaten only by Alaska. Yet New Hampshire has the best performance of any state on our Index of Health and Social Problems and is closely followed by Vermont which is third best. They both also do well on equality: despite their radically different taxation, they are the fourth and sixth most equal states respectively. The need for redistribution depends on how unequal incomes are before taxes and benefits.

Both the international and US state comparisons send the same message: there are quite different roads to the greater equality which improves health and reduces social problems. As we said in Chapter 13, what matters is the level of inequality you finish up with, not how you get it. However, in the figures there is also a clear warning for those who might want to place low public expenditure and taxation at the top of their list of priorities. If you fail to avoid high inequality, you will need more prisons and more police. You will have to deal with higher rates of mental illness, drug abuse and every other kind of problem. If keeping taxes and benefits down leads to wider income differences, the need to deal with the ensuing social ills may force you to raise public expenditure to cope.

There may be a choice between using public expenditure to cope with social harm where inequality is high, or to pay for real social benefits where it is low. An example of this balance shifting in the wrong direction can be seen in the USA during the period since 1980, when income inequality increased particularly rapidly. During that period, public expenditure on prisons increased six times as fast as public expenditure on education, and a number of states have now reached a point where they are spending as much public money on prisons as on higher education.

364

Not only would it be preferable to live in societies where money can be spent on education rather than on prisons, but policies to support families in early childhood would have meant that many of those in prison would have been earning and paying taxes instead of being a burden on public funds. As we saw in Chapter 8, pre-school provisions can be a profitable long-term investment: children who receive these services are less likely to need special education and, when they reach adulthood, they are more likely to be earning and less likely to be dependent on welfare or to incur costs through crime.

365

POLITICAL WILL

It is tempting to say that there are two quite different paths to greater equality, one using taxes and benefits to redistribute income from the rich to the poor, and the other achieving narrower differences in gross market incomes before any redistribution. But the two strategies are not mutually exclusive or inconsistent with each other. In the pursuit of greater equality we should use both strategies: to rely on one without the other would be to fight inequality with one arm tied behind your back. Nevertheless, it is worth remembering that the argument for greater equality is not necessarily the same as the argument for big government. Given that there are many different ways of diminishing inequality, what matters is creating the necessary political will to pursue any of them. Whenever governments have really wanted to increase equality, policies to do so have not been lacking. Although discussion of policy alternatives must precede action, what is best will differ from one country to another.