The Star of the Sea (38 page)

Read The Star of the Sea Online

Authors: Joseph O'Connor

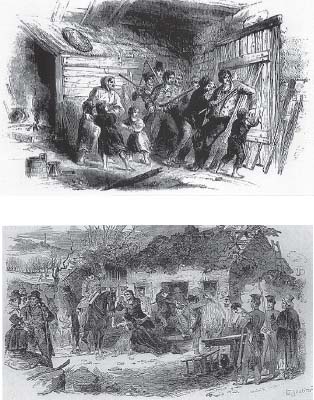

Mounds of soggy ashes. Scorch marks on the flagstones. A shovel handle thrust through a lichened windowpane.

The breeze off the lake was surprisingly warm and it brought the faint redolence of rushes and summertime. But now he saw something that made him feel cold. The door of the cabin had been sawn in two. He knew what it meant. The eviction gang.

Nobody was nearby. The fields were deserted. A fisherman’s currach was mouldering near the gateposts, its cross-ribs bleaching where the canvas had rotted away.

He left the wrecked cottage, intending to go up to the manor. He would ask what had happened. Where had everyone gone? As he walked, he became aware that he was stumbling in panic. Another broken bothy. A burnt-down pigsty. Barbed wire across the bogland. A goat’s crusted shinbone. A smashed, rusting bedstead upended in a boundary ditch. A daubed table-top as a signboard, hammered into a midden.

THESE LANDS ARE THE PROPERTY OF

HENRY BLAKE OF TULLY

.

TRESPASSERS WILL BE SHOT

WITHOUT FURTHER WARNING

An old man appeared on the boreen leading an unkempt pony.

‘God be with you,’ said Mulvey in Irish.

‘And Mary with yourself,’ the old man replied.

‘Are you a local man, sir, if you don’t mind me asking?’

‘Johnny deBurca. I worked above at the manor one time.’

‘I’m seeking Mary Duane that lived down by the bayside.’

‘There’s no Duanes here no more, sir. There’s nobody here.’

It swam up at him like a nausea that she might have emigrated with the child. But the old man said no, she was still living in Galway. At least he thought as much, if they were speaking of the same woman.

‘Mary Duane,’ said Mulvey. ‘Her people are from Carna.’

‘You mean Mary Mulvey as lives up near Ardnagreevagh.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Mary Mulvey that married the priest, sir. Twelve year ago now, I believe it is.’

‘– The priest?’

‘Nicholas Mulvey, aye. That used to be the priest. Brother of him that got her in pup and scuttled off to America.’

How the prisoner and the immigrant are treated by the government, how the poor are treated and those without influence: this is secretly how the government would like to treat all of us.

David Merridith

From notes for a pamphlet on penal reform. 1840. Unfinished

1

See Henry Mayhew’s monograph ‘The Speech and Language of the London Poor’ (1856).

‘“Freddie”

’ (n):

a fatally violent assault. “To Freddy” (vb): to attack or to murder. “Freddying” (adj.): an expletive common among criminals and women of a certain character

.’ Soon the term entered the lexicon of literature. To freddie an author was to give him an unnecessarily harsh review. – GGD

THE LAW

T

HE

SEVENTEENTH

DAY OF THE

V

OYAGE: IN WHICH THE

C

APTAIN RECORDS THE

DELIVERANCE

OF

M

ULVEY

FROM A PRECARIOUS ENCOUNTER WITH

RETRIBUTION.

Wednesday, 24 November, 1847

Nine days at sea remaining.

L

ONG:

47°04.21′W. L

AT:

48°52.13′N. A

CTUAL

G

REENWICH

S

TANDARD

T

IME:

02.12 a.m. (25 November). A

DJUSTED

S

HIP

T

IME:

11.04 p.m. (24 November). W

IND

D

IR

. & S

PEED:

N.N.E. (38°) Force 5. S

EAS:

Turbulent. H

EADING:

S.S.W. (211°). P

RECIPITATION

& R

EMARKS:

Shower of very large hailstones in the afternoon. Raw, severe wind. The bad smell recently reported about the ship would appear to be diminishing.

Last night two steerage passengers died: Paudrig Foley, farmhand of Roscommon, and Bridget Shouldice, neé Coombes, aged serving woman, latterly inmate at Birr Workhouse in King’s County. (Insane.) Their remains were committed to the sea.

The total who have died on this voyage is now forty-one. Seventeen isolated for cholera in the hold.

I am compelled to relate a series of troubling incidents, which arose this day and greatly disturbed the peace of those in steerage, with distressing and almost calamitous results.

At three o’clock approximately I was in my quarters studying the charts and attending to some engrossing matters of calculation when Leeson came in. He said he had been told by a young woman of steerage that there was considerable unrest among the ordinary passengers and if I did not hasten with him there might be murder

before we were done. This was no innocuous donnybrook but a veritable carnival of thuggee. He insisted we take two pieces from the lockbox, for the passengers were in a very frenzy of anger. We then set out.

Making our way along the maindeck we came upon the Reverend Henry Deedes at meditation, and I prevailed upon him to accompany us below. For although most of those in steerage are of the Roman faith, they regard all men of the cloth with respect and approbation and I considered it might be advantageous to have him with us.

When we went down the ladders to the hatch (Deedes and Leeson and self) a dreadful scene was being enacted. The unfortunate crippled man, William Swales, was cowering on the floor near the water closets. His appearance was most pitiful. By the marks upon his person it were easily deducible that he had been victim of an assault, or several prolonged assaults. His clothes were pulled apart and he was shaking in fear, his face a pulp of blood and unspeakable filth and ordure.

At first the passengers refused to say how this had happened, and even the wretched man himself was greatly reluctant to speak of it, insisting that he had fallen down while inebriated and would soon be happy again. It must be noted that among the common class of Irish exists the general and curious custom of not informing to any person they perceive to be in authority of the shortcomings and crimes of their fellows, be they ever so dastardly. And until I promised that the rations would be halved forthwith, and the company’s rules relating to on-board drinking more strictly enforced than had been the case hitherto, silence was maintained. It was only at the issuing of these latter threats that the full concatenation of events began to be disclosed.

It was revealed that there had been a theft from a passenger called Foley of a cup of Indian meal and this crippled man was suspected. This was adduced as the cause of his punishment. I said the ship sailed under the law of England and in the eyes of that law was

part of England’s territory

; and under that same benign law a man was innocent until he be proven otherwise, be he ever so great or ever so small. And if any man dared to raise up trouble on my vessel or take the law in his own hands, he would be confined and fettered for the

remainder of the voyage the better to ponder his philosophies. The good Minister then spoke up, saying it was not Christian to abuse an unfortunate man without so much as knowing him and he a cripple and did Our Redeemer not take pity on such & cetera.

‘I know him,’ then issued a retort from the back.

The crowd parted to reveal one Shaymus Meadowes, a violent passenger much given to thieving and foolery of the lowest kind and exposing himself. He is quite given over to drinking and its attendant train of ruffianly debasement and has a face like a robber’s dog. Only this morning had he himself been released from the lock-up and then only at the great intervention of Minister Deedes who had befriended him and made kindly intercession on his behalf.

‘Your name is Pius Mulvey,’ said he. ‘You took a neighbour-man’s land off him when he was down on his luck.’

(Among these Irish of the villein class there is no man lower than he who has taken the holding of another in such a circumstance. They had rather the land were left idle and barren than it be husbanded by one who was not born on it.)

‘You are after confusing me with somebody else,’ said the cripple. ‘My name is not Mulvey.’

At this he began to limp away, his appearance most greatly alarmed.

‘I believe and know it is,’ said the other. ‘For I seen you often with that leg of yeers.’

‘No,’ said the cripple.

‘Your neighbour was put out – evicted I say – by that “shoneen” b*****d Blake of Tully, may he die choking in his own sh*t.’ (Other remarks which may be imagined were then made, concerning one Commander Henry Blake, a personage not at all popular among the Connermara poor.) And he went on: ‘Stead of shunning that filthy b*****d of a landlord, you got the lease of your neighbour’s land off him and got it cheap, too.’

At this a great clamour of insults and spitting arose. ‘I’d crack the head of him if I had the strength,’ said one. ‘A worse man never faced the sun,’ said another, a woman, and she called for a noose to be made. (It is distressing to note in these situations that the women are sometimes the worse offenders than the men.)

‘His name is William Swales,’ said I.

‘The “divil” goes by many names,’ cried Meadowes. ‘He is Pius Mulvey of Ardnagreevagh as I live and breathe. Who done another man to death through his cruel robbery.’

Some began to roar again. Once more the Reverend Deedes attempted an intervention but was himself now abused and called horrid names that touched upon his religious persuasion. I did have to assert that judicious and sincere holiness is the inheritance of no particular faction, but that the banner of true religion while it contains an assemblage of distinct threads affords decoration and pride to the whole world by their intimate coalescence. I was myself mocked at this point.

By now Meadowes had the floor and was enjoying fully his celebrity and determined on that (as such men will be who are always unproductive in any sphere save bragging and bullying).

‘Will I tell them the best part?’ said he.

No rejoinder came from the cripple. He was so afraid.

‘Beg me not to,’ said the first, a horrid smile on his lips.

‘I beg you not to,’ the cripple pleaded.

‘On your knees, beg me not to,’ said Meadowes.

The poor cripple sank to the boards and commenced to weep quietly.

‘Call me God,’ said Meadowes. ‘You crown-shawning c**t.’

‘You are my God,’ exclaimed the cripple through his tears.

‘That’s right now,’ said Meadowes, the low scoundrel. ‘And you will do all I command.’

‘I will,’ said the cripple. ‘Only have mercy on me, I beg you.’

‘Lick the filth off my boots,’ Meadowes ordered, and his wretched victim commenced to do so. At this performance of disgraceful cruelty many of the passengers laughed in mockery; though many again, kinder among them, called for it to stop.

‘Please,’ said the cripple, ‘do not tell on me, I beg it.’

Meadowes bent low and spat into his face.

‘The neighbourman you did was your own brother,’ said he.

‘Lies!’ cried the cripple.

‘Nicholas Mulvey that was once the priest up in Maam Cross. I knew him well. A good decent man, Christ give his soul rest. And his blood is on your hands for certain sure. You murdered him! You

murdered your brother!’