The Star of the Sea (47 page)

Read The Star of the Sea Online

Authors: Joseph O'Connor

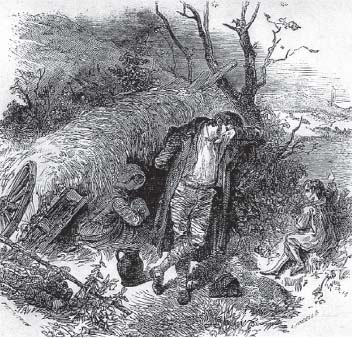

we could pay nothing owing to the blight and to p**s M***** killing our cow. blake would not allow us credit but put us out on the road itself. it was p**s M***** took over our land then and he breakin his smig laughing at us as we were put out. we went down to rossaveel and lived in a scalp my husband dug above in the woods, myself and my husband and my infant wean in dirt while p**s M***** took our rightful land and he lording it. he is still up there now like the king of england

.

he was spat on and thrun stones at by the people at his own brothers funeral and shunned but not one of them did a screed to help me

.

it was hard times I had after my husband and child died. it was the workhouse for me until i coulden thole it no more. i went all the road to dublin and lost another child on the way. i had to beg in the street for nigh on a year and do what no woman should ever have to do in that place. i am now a nanny and am going to america. i am working as a nanny for the family of Lord and Lady

********* .

i will never come back to galway again an i live to a hundred. there is no use in galway for a decent woman

.

everything said by the people about p**s M

*****

is true. i denounce him as a land robber, a seducer and a blackguard. he is after harryin his own brother and my only child into a grave and i would like something done on him by you and yeer men.

i know well ye have done it to others before

.

3

ye will know him because he has a camath

4

way of walking having only one foot and a wooden one marken M (for murderer, it might as well be). any fate in store for him he deserves it. while a cullion the ilk of himself is allowed to do what he will it is no wonder but the people are put down so low in these times. i do not know how so called irish men can allow it

.

that the child of my womb be in hell this day if i am after telling word of a lie here. it’s one foot he has and a gun-stone for his heart

.

the dogs of Connamara know the truth of what i say

.

i denounce him every way i can, the blackest craven cur that ever wore shoe leather and rotted the land of galway by his walking on it

.

god send he die in screams of shame

Mary M***** (nee D****)

Do not wait ingloriously for the famine to sweep you off – if you must die, die gloriously; serve your country by your death, and shed aroud your names the halo of a patriot’s fame. Go; choose out in all the island two million trees, and thereupon

go and hang yourselves

.

John Mitchel, ‘To the Surplus Population of Ireland’ 1847

1

Document discovered five years after the voyage by detective employed in Dublin by GGD. Fair copy. Original lost. Entered in prosecution evidence at Galway assizes, 6 June 1849. ‘Being in the matter of the trial of James O’Neill labourer, formerly of Kilbreekan nr. Rosmuck (evicted), alias “Captain Moonlight” or “Captain Dark” of an agitational society, namely “The Hibernian Men”, “Hibernian Defenders”, “Liable Men” or “Else-Be-Liables”; on charges of Destruction of Property, Common Assault, Assault on a Constable, Conspiracy to Murder, Inciting or Suborning another Person to Murder and Membership of a Named and Prohibited Organisation. Document found by constables in a search of the shelter of the accused on Hayes’s Island.” (He was hanged in Galway Barracks on 9 August 1849. Two of his sons were later transported for life to Botany Bay for membership of ‘The Irish Republican Brotherhood’ or ‘Fenians’.) Names excised by the Court Reporter.

2

Irish: ‘to sufficiency’. Origin of the English word ‘galore’ – GGD

3

This phrase underlined and initialled by the Crown Prosecutor’s Office, Dublin Castle.

4

‘

Camath

’: possibly a mis-spelling of a dialect word for limping, or a conflation of ‘

cam

’, Irish for ‘crooked’, and ‘

gyamyath

’, Shelta cant, meaning ‘lame’. – GGD

THE LOST STRANGERS

T

REATING OF THE

TWENTY-SECOND

DAY OF THE

V

OYAGE; IN WHICH A

G

RIM

D

ISCOVERY IS RECORDED BY THE

C

APTAIN; (WITH A SOMBRE

R

EFLECTION ON THOSE WHO MUST LEAVE THEIR LANDS; AND OTHER MATTERS TOUCHING THE

C

HARACTER OF THE

I

RISH PEOPLE

).

Monday, 29 November, 1847

Four days remaining at sea

L

ONG:

54°02.11′W. L

AT:

44°10.12′N. A

CTUAL

G

REENWICH

S

TANDARD

T

IME:

03.28 a.m. (30 November). A

DJUSTED

S

HIP

T

IME:

11.52 p.m. (29 November). W

IND

D

IR

. & S

PEED:

S.S.W. Force 7 (last night Force 9). S

EAS:

Still heaping severely. H

EADING:

N.W. (315°). P

RECIPITATION

& R

EMARKS:

Driving rain most of the day. Fogbank to north

‘Is there no balm in Gilead?’ Jer. 8: 22

Last night four of the steerage passengers died; and this morning they were buried according to the rite of the sea, RIP. Their names: Owen Hannafin, Eileen Bulger, Patrick John Nash and Sarah Boland; all four of the county of Cork in Ireland.

This day was made a dreadful discovery.

The bowsprit mast had snapped in the storm of last night and its rigging had become entangled in the chains at the waterline. Bosun Abernathy had rope-climbed down the hull with some of his crew when he saw a very large infestation of monstrous rats which had congregated in the sewerage-gulley channel leading from the First-Class quarters: an aperture of perhaps four feet in diameter.

Thinking to discover the source of the odour on the ship of late, he approached with some of the men to make an investigation. A piteously sorry sight was soon met.

The badly decayed remains of a youth and a girl were lying in the drainway; side by side, still enfolded in each other’s embrace. Surgeon Mangan was called to pronounce death. The lad was about seventeen yrs; the girl perhaps fifteen. The girl had been several months with child.

I confess there are bitter tears in my eyes, even as I set down these words.

Nobody is unaccounted for on the Manifest of Passengers; so it must be assumed that these poor frightened people had been concealed there ever since we left Cork; or Heaven help them, even Liverpool. They must have climbed down the chains and got into the culvert, thinking to hide themselves there until we arrived at New York. As Leeson pointed up, the very many extra passengers we took on at the Cove are making us lie much deeper than is usual in the water.

A number of children were playing on the deck and I ordered them sent below.

We took them out and gave them a Christian rite as best we could; but they had nothing at all by which we might even discover their names. Many of the men were extremely distressed, even those who have seen many hard things at sea. I myself was overcome as I attempted to say the words and had to be helped by the men. Reverend Henry Deedes also assisted me and said a simple prayer. ‘That these children of God; of Ireland or England; each of whom was child of a mother, and each of whom was beloved of the other, may find their safe home in the arms of the Saviour.’ Afterwards the men and I sang a hymn. But it was very hard to sing anything today.

How I thought of my own dear wife and our beloved children; wishing I had them about me now. How I reflected that every little quarrel of married life may be ascribed to the very contiguity which that state brings, such as which exists between coterminous realms. And – most painful – how I thought of my own treasured grandson and wished I could embrace him for even an instant.

For me to leave my own happy situation and away to sea is such a painful thing; even after all these many years. What anguish, then,

must be endured by those on board who will never again in this life see their loved ones who must remain behind? The man who will never more go walking in the evening in his home town with his brother, quietly reflecting together on the matters of the day. Or the girl who must bid farewell to respected parents whom she knows to be too poorly to countenance such an arduous voyage. The happy young couple who must part from one another and the father parted from his wife and children, to travel into America by himself where the means only exist to pay for one passage. To wander alone among strangers, they risk all.

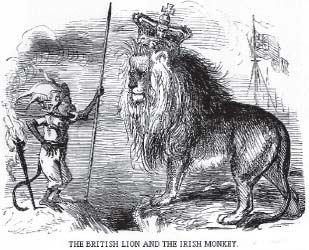

And these, may God help us, are among the luckiest of their people. They are not the poorest of the poor of Ireland, who are almost entirely without means of any kind. ‘The basest beggars are in the poorest thing superfluous,’ says the bard; but not so in the tortured country of Connaught. Many of the western part of that place own almost and oftentimes literally nothing. A few manage to scrape a means across to Liverpool or London. There they become enchanted by unscrupulous ‘immigration agents’ who prey among them like leeches and thieves; robbing them of their very clothes by times; or a man of the tools by which he might labour in the natural and dignified way for his family; and in return spirit them on to some vessel at night, making false promises of riches in the new land.

The situations in which they sail are hideous in the extreme and would make the privations which must be endured on the

Star

seem as a Paradise. Sometimes the vessel is not even bound for America, but for any country or territory out of Great Britain; no matter how unfriendly or cold it were.

And it is all so bitterly unmerited. For as truly as the night comes down on every day, if the world were somehow turned downside-up; if Ireland were a richer land and other nations now mighty were distressed; as certain as I know that the dawn must come, the people of Ireland would welcome the frightened stranger with that gentleness and friendship which so ennobles their character.

I can write no more. There is no more to be written.

I am sorry I was ever born to see this day.

If any class deserves to be protected and assisted by the government, it is that class who are banished from their native land in search of the bare means of subsistence

Charles Dickens,

American Notes