The Starbucks Story (12 page)

Read The Starbucks Story Online

Authors: John Simmons

In between these shops are scores of others, all individual and different, yet all unmistakably Starbucks. It’s a difficult trick for any brand to pull off, but Starbucks does it not just across one American city but every US state and 32 different countries.

The foundations were made strong by the work of Scott Bedbury. The greatest advantage from the kind of information followed by analysis that Scott instituted was that from 1996 onwards, and perhaps for the first time, Starbucks had a rational means of making decisions about how to develop its business. The brand provided a touchstone, a steady guide to decision making. Previously Starbucks had relied simply on the intuition of Howard Schultz and its own people. Those who “got” the brand but could not articulate it, and those who did not “get” the brand and so could not fully accept its obligations, were sometimes left agonizing. As Starbucks got bigger, the danger that people would not have that intuitive understanding grew. The wrong decisions could easily be made for perfectly good reasons. For example, opportunities kept coming up to sell more volume through a partnership, and to make more money as a result. Now, with a stronger sense of what the brand stood for, it was easier to say no to ventures that might make money in the short term but destroy reputation in the longer term.

A tool that Scott Bedbury imported from Nike was the brand mantra. This is simply a short phrase – not a strapline that runs in advertising – that sets out the essence of the brand. It is not something that the outside world ever sees or hears through direct communication. Indeed, many of the internal audience may never hear the mantra presented, although they should all be able to recognize its truth. But the philosophy behind it is never frame it, never put it on the wall.

For Starbucks, the equivalent of Nike’s “Authentic athletic performance” became “Rewarding everyday moments.” No mention of coffee, although the mantra clearly fits with the idea of treating yourself to a coffee, a Frappuccino, a tea, a juice, a muffin, a quiet read or an animated conversation. As a description, it is tight enough to the brand but also baggy enough to allow creative development over time. The mantra works because it taps into the emotional triggers of the brand, the need to reward ourselves in stressful times, to rise above the humdrum, to see the possibility of the extraordinary in the ordinary. When we drink a cup of coffee in Starbucks we are fulfilling a deeper need than the quenching of thirst. As Scott Bedbury put it: “Consciously or not, we seek experiences that make us think, that make us feel, that help us grow, and that enrich our lives in some way.”

The longevity of this approach was brought home to me in October 2003, eight years after The Big Dig. I visited the newly refurbished Hayward Gallery on London’s South Bank to see an art exhibition. Afterward, I went into the new Starbucks located inside the gallery. It’s an elegant little shop, with stylish furniture that sits with the feel of an art gallery, providing “the finest coffee and stimulating art in a space where you can be inspired, connect, escape and enjoy.” And on the chalk board, the following words have been handwritten by the barista: “Starbucks at the Hayward. Art demands time and thought. Good excuse for a muffin.”

*

In 2003 Starbucks bought Seattle’s Best Coffee, a smaller local company that flavors its beans. The SBC shops are not adopting the Starbucks brand and will continue selling flavored beans.

*

Having just flown to Seattle on United, I can say that the partnership is still working and the coffee is good, although it still tastes better on the ground.

You know when a brand has become an everyday part of our lives. It enters popular consciousness and becomes a reference point that everyone understands and laughs at. In the 1990s, the comedian Janeane Garofalo appeared on a TV comedy show and joked, “They just opened a Starbucks – in my living room.”

Equally you know that a brand has reached a position of confidence about itself when it uses such jokes in its annual general meeting. Investors at the introduction of the 2003 annual report were shown a video with a whole succession of clips about Starbucks, including the following from a spoof news report: “The iceberg is easy to spot because it’s 50 miles long and has three Starbucks.”

From this it seems that Starbucks has come to terms with its own ubiquity. Perhaps it senses that the world has, too. Over the last ten years, life for Starbucks has been a roller-coaster ride, but two particular streams have consistently run through everything. The first is increasing internationalization, which will be dealt with in this chapter. The second, against the background of debates about globalization and a growing distrust of corporate America, is Starbucks’ commitment to communities, which I will cover in the next chapter.

By 1995, Starbucks had emerged as the US speciality roaster that could bring you real coffee in the form of beans to your home or an espresso to your high street. The big coffee merchants had overslept; they simply had not noticed the significance of what was happening. Yet Starbucks was still a North American phenomenon. The company had expanded out of its north-western corner of the US into the major cities and into parts of Canada. It had even opened in New York, despite misgivings and analysts’ doubts about whether the concept was truly portable. Queues outside the shop seemed to indicate that it was. In many ways New York strikes me as a separate country within America. Perhaps “conquering” it gave Starbucks the final proof it needed that it could and should export its concept to other countries. To do so, it put Howard Behar in charge of international development.

It was a sign of growing confidence in the brand. Starbucks had always insisted on the need to build the brand one cup at a time, one person at a time, and this focus on the individual customer became one of the building blocks of the brand. Indeed, “one brick at a time” seemed to be the way the brand was built strong. The third place. The mission statement. The principles and values. The brand mantra. There were now many building blocks that reinforced each other, whereas with other brands such a plethora of statements would imply internal contradictions and confusion.

One other statement of positioning, associated with the concept of the third place, became another of these building blocks. The statement went along these lines: Starbucks offers a

taste of romance

because it provides a touch of the exotic in everyday life, with coffees from around the world. It is an

affordable luxury

that brings a certain democracy because its products, although often premium priced, are still reasonable as a treat to most people. Starbucks provides an

oasis

where people can take quiet moments to gather themselves and their thoughts. And it offers a place for

casual social interaction

that works even though the result is often the sociability of being out in the world while remaining private with your own thoughts.

In even simpler terms, it became clear that for customers, the Starbucks brand was in almost equal parts about the

coffee

, the

people

and the

experience

. The way this was achieved was through a word that is one of Howard Schultz’s favorites: romance. So Starbucks needs to

romance the bean

, which means being fanatical about the quality of the coffee bean itself and about every step that is taken to place a cup of coffee before the customer. It means sourcing the best arabica beans, shipping and storing well, roasting the beans to an exact specification, and grinding, brewing and serving them to high standards. Every detail matters, including the quality of the water and the time it takes (between 18 and 23 seconds) to make the perfect espresso. This all makes a narrative in itself that provides an element of romance because it goes way beyond measuring a spoonful into a cup and pouring on boiling water. In other words, it’s easy to make a bad cup of coffee, but there’s something of an art in making a good one.

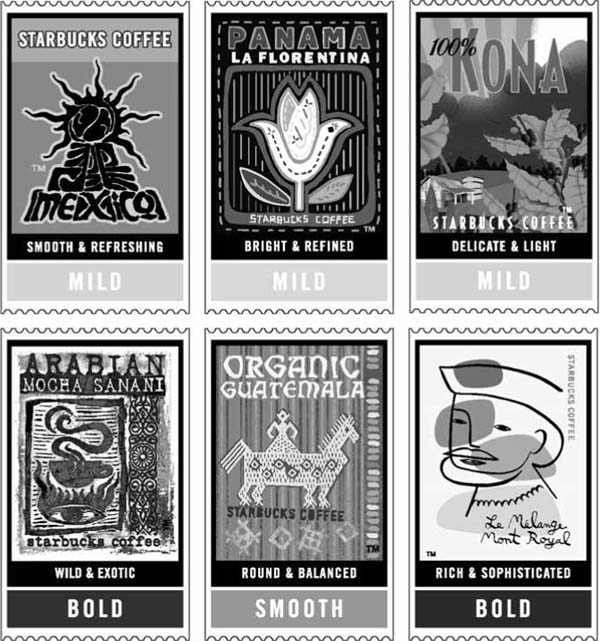

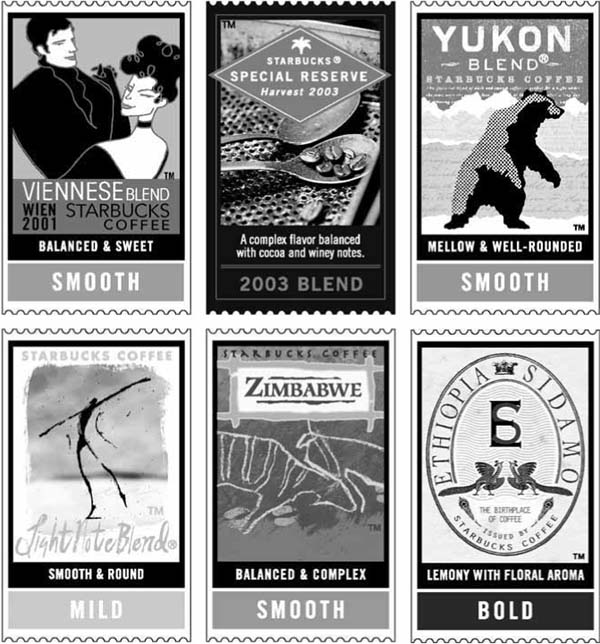

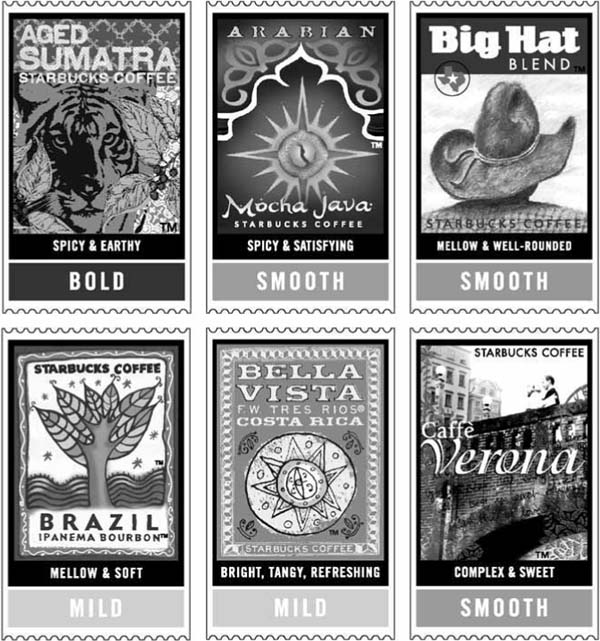

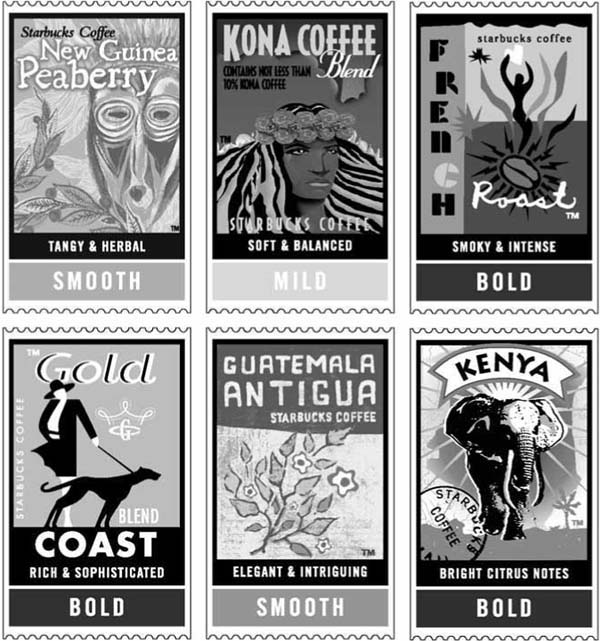

The range of Starbucks’ coffee is part of the romance of the bean