The Story of Rome (40 page)

No longer need they live in dread of the sudden appearance of the ships with scarlet sails and silver oars along the Italian coasts, no longer need they fear the sudden capture of their corn. And this was due to Pompey! In Rome at this time no one was so popular as he.

His success determined the Senate to send him to take command of the war that was going on in the East, against Mithridates.

Lucullus had been in the East at the head of the army for some time. But the Senate refused to send him money to pay or to clothe his men, and they had grown rebellious, and had begun to grumble at his strict discipline. They wished Pompey the Great to come to take command of them, and then they would do great deeds. So in 66

B

.

C

.

Pompey was appointed commander of both army and navy in the East, to the delight of soldiers and sailors alike.

Pompey himself seemed none too pleased at the honour conferred on him.

"Alas, what a series of labours upon labours," he cried, frowning as he spoke. " If I am never to end my services as a soldier . . . and live at home in the country with my wife, I had better have been an unknown man."

These were unsoldierly words, but his friends paid little attention to them, believing that he did not mean them seriously. And his deeds were proof that he longed to win glory for himself and his country, although he never risked any great adventure on the battlefield.

Mithridates had little hope of withstanding Pompey, when he had barely been able to hold his own against Lucullus. However, he encamped in a strong position on a hill, and hoped that this would make an attack difficult, perhaps even impossible.

Pompey, leaving his fleet to guard the seas, marched into Pontus, but not before the king had been driven from the hill on which he had entrenched himself, by lack of water for his army.

The Roman general had more discerning eyes than the old king. For he, noticing that the plants were green and healthy, encamped on this same hill, and when his soldiers complained of thirst he bade them dig wells. As he expected, there was soon abundance of water in the camp.

But Pompey did not linger long on the hill, for he was eager to follow Mithridates, and soon after this the king found his camp besieged so closely by the Romans that it was impossible to get supplies for his army. It was plain that he and his soldiers must either starve or escape.

So one night Mithridates ordered the sick and wounded to be killed, for they would have hampered the army in its fight. The king did not hesitate to give such a cruel order, for he and his followers had not been taught to pity the weak and helpless.

The watch-fires were lighted at the usual time, that the suspicions of the Romans might not be roused. Then when the camp seemed quiet for the night, Mithridates and the main body of the army slipped out into the dark, and somehow succeeded in passing unnoticed through the Roman lines.

In dread of pursuit, they hid themselves by day in forests, at night they marched as quickly as possible toward the river Euphrates.

When Pompey found that Mithridates had escaped, he blamed his own carelessness and followed swiftly in pursuit. As he marched by day as well as by night, he was soon in advance of the king. So it happened that when Mithridates encamped by the banks of the river Euphrates, the Romans were already there, and determined that the enemy should not again escape.

But the very first evening as it grew dark Pompey became restless. He had set a strict watch, it was true, yet Mithridates had already shown himself skilful in evading sentinels. It would be safer to attack the camp without delay. Pompey summoned his officers, and arranged that the assault should take place at midnight.

Meanwhile, Mithridates lay asleep in his tent, worn out with fatigue and anxiety. As he slept, his troubles slipped from his mind, and the old king dreamed pleasant dreams. He thought that he had reached the sea, and was in a ship. The winds blew soft and fair, wafting the vessel quietly along toward a harbour where no foes could touch him.

In his dream the king began to tell his friends how pleased he was to have reached so safe a haven, when suddenly the wind rose, lashing the sea into fury. The king grasped a spar, but his strength failed, and he was beginning to sink, when he awoke, and lo! it was a dream.

At that moment his officers rushed into his tent, to tell him that the Romans were preparing to attack them.

Swiftly the king shook off the effects of his dream, and ordered his troops to defend their camp to the last.

Now, as the Romans approached the enemy, the moon rose behind them and cast their shadows on the ground.

The soldiers of Mithridates saw the black flitting forms and grew bewildered. In the indistinct light they thought the shadows were the real soldiers and they flung their darts at these imaginary foes.

Then with a great shout the Romans rushed in upon the puzzled enemy, fear was at once added to their confusion, and in sheer panic they turned and fled. But more than ten thousand were killed, and their camp was taken.

Mithridates himself once more escaped. At the head of about eight hundred horse he made a desperate charge through the enemy's lines, and then in the darkness of the night he was seen no more.

Pompey did not follow the king further. But he stayed in the East to fight, and by his skill he won many new territories for Rome.

He even marched to Palestine, where the city of Jerusalem soon surrendered to the powerful enemy that had surrounded her walls. But the Jews refused to give up their temple, and for two or three months they defended their holy place bravely against every attack.

In December 63

B

.

C

.

, however, it was taken, and Pompey, who had entered many temples and seen many pagan gods, now entered the temple of the Jews.

Nor would he be content until he had penetrated into the Holy of Holies, where the High Priest alone might enter once every year. Here he saw the golden table and the golden candlesticks, of which you have read in Old Testament stories. But the Roman, although he felt a Presence there, looked in vain for the God of the Jews, for His dwelling is in a house "not made with hands."

While Pompey was still in Palestine, he heard that the king whose rebellion had brought him to the East was dead.

Forsaken by his allies, deserted by the one son who was still alive, Mithridates had cared to live no longer, and had taken poison, which he had carried with him in the hilt of his sword.

After his death there was no one to lead an army against the Romans. So the rebellion in Asia came to an end, and Pompey the Great was free to return to Italy.

Once again the Roman citizens wondered what would happen when he came. Would his many victories have changed the conqueror into a tyrant ? But once again the people found that their fears were groundless. For as soon as he landed in Italy Pompey disbanded his army and set out for Rome, attended only by a few friends.

When the Italian cities saw Pompey the Great journeying in this simple guise they determined to send him to Rome in more suitable fashion.

So, in happy, careless mood, the citizens crowded around him, and themselves became his escort. In such multitudes did they follow him that they were more in number than the troops which he had disbanded.

Never was such a triumph as Pompey held! Although, indeed, he had to wait more than nine months before he was allowed to hold it.

His long list of victories was written on tablets that all might read. Kings, princes, chiefs were led in chains in his procession, while the temples of Rome were enriched by the treasures that he had brought from the East.

Plutarch, who writes the life of Pompey, says, that he seemed to have led the whole world captive, for his first triumph was over "Africa, his second over Europe, and his third over Asia."

CHAPTER CIII

Cicero Discovers the Catilinarian Conspiracy

T

HE

excitement caused by Pompey's return to Rome was soon over. Then the great general found that, in spite of all that he had done for his country, and in spite of the splendour of his triumph, there were many in the city who did not welcome his return.

His very first request to the Senate was refused, and it may be that Pompey thought half regretfully of his disbanded army. To it his slightest wish had been law. The Optimates, too, had grown used to his absence, and were ready to thwart or ignore him.

So Pompey determined to join the two most powerful men in Rome at that time. One of these was the wealthy Crassus, the other was Julius Cæsar, who was destined to become the greatest man Rome had ever known.

Pompey did not like Crassus, and he soon became jealous of Julius Cæsar. But in the meantime these three men formed a secret union, for they thought that then they alone would govern Rome. This union was afterwards called The First Triumvirate. When Pompey married Julia, the beautiful daughter of Cæsar, it seemed probable that the father and husband would share many interests.

For a time another great man named Cicero threw in his lot with the three leaders. It is of him that I wish to tell you now.

Cicero was a great orator and man of letters. In 63

B

.

C

.

he was chosen Consul. During the lifetime of Sulla, Cicero's influence was used on behalf of the plebeians. But before long his reverence for the Rome of the past made him ready to denounce any side which threatened to disregard the ancient laws.

In the end he joined the Optimates, because he believed that if they would cease to live only for pleasure, and would learn to govern the provinces with justice, the old order of things might be restored.

By eloquent speeches he tried to rouse the nobles to live more useful and upright lives. But they paid little heed to his words, partly, perhaps, because they did not find that his teaching rang true. For they knew that he did not always act justly although he bade them do so, that he often used his eloquence to defend his friend or his party, when it was plain that the cause of neither was just. And so his words had not the power which true words always have.

Two years before Cicero became Consul, Rome had been greatly disturbed by the discovery of a plot to kill the Consuls, to seize the government, and even to burn Rome.

This plot, which was never proved, was known as The First Catilinarian Conspiracy, for Catiline, who had belonged to Sulla's party, was said to have planned it.

In 63

B

.

C

.

Cicero declared that a new plot was being prepared by the same leader.

Catiline had gathered around him a band of the wildest of the popular party. His followers hoped that Catiline would be elected Consul, and that then he would reward them. One of the ways in which he could do this would be by passing a law for the abolition of debts.

But Catiline was not chosen Consul, while Cicero was. It was then, in his rage and disappointment, that Catiline was said to have made a deliberate plot to assassinate Cicero, to attack the houses of the senators, and to burn the city. While this was being done, an invading army was to march into Rome.

Now there seemed reason to be alarmed, for it was known that troops were assembling near Fæsulæ, a small town about three miles from Florence. And not only so, but their captain was Manlius, an old officer of Sulla. Since the terrible proscriptions, it was natural that any one who had been connected with Sulla was feared as well as hated.

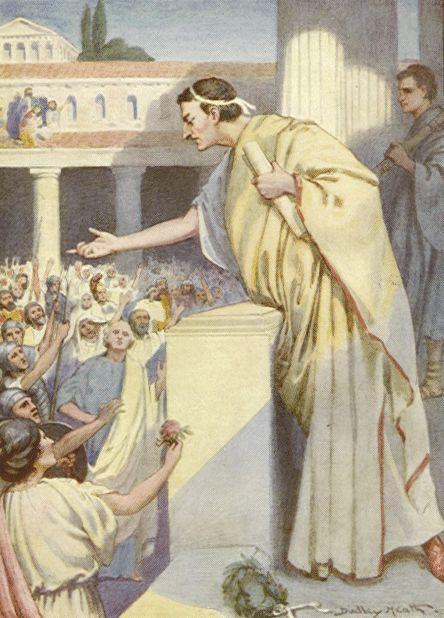

Although Cicero had no doubt that a plot was on foot, he could not find proof enough to arrest the conspirators. Yet at a meeting of Senate, early in November, the Consul rose, and in a vehement speech denounced Catiline, who was present. The conspirator sat apart from the other senators, for he knew that they were suspicious of him.

When Cicero's speech ended, Catiline begged the Senate not to judge him hastily, and then he left the Assembly.

That same night the conspirator left Rome apparently for Marseilles, where, if a Roman chose to live in exile, he could escape being impeached by his fellow-citizens.

On his journey, Catiline wrote a letter to a friend, begging him to protect his wife, and at the same time he assured him that he, Catiline, was innocent, "save only that he wished to help his countrymen who were poor and downtrodden."

The following morning Cicero made another speech against Catiline, and as the people clamoured to know why the conspirator had been allowed to escape, the Consul confessed that he had not proof sufficient to arrest him.

The following morning Cicero made another speech against Catiline.

Before long the city was startled to hear that the fugitive had not gone to Marseilles, but to the camp at Fæsulæ, where he was now in command of the army.

CHAPTER CIV

The Death of the Conspirators