The Story of the Greeks (Yesterday's Classics) (16 page)

The Theseum

Cimon showed his patriotism in still another way by persuading the people that the remains of Theseus, their ancient king, should rest in the city. Theseus' bones were therefore brought from Scyros, the island where he had been killed so treacherously, and were buried near the center of Athens, where the resting-place of this great man was marked by a temple called the Theseum. A building of this name is still standing in the city; and, although somewhat damaged, it is now used as a museum, and contains a fine statue of Theseus.

The Earthquake

C

IMON

,

as you have already seen, was very wealthy, and as generous as he was rich. Besides spending so much for the improvement of the city, he always kept an open house. His table was bountifully spread, and he gladly received as guests all who chose to walk into his home.

Whenever he went out, he was followed by servants who carried full purses, and whose duty it was to help all the poor they met. As Cimon knew that many of the most deserving poor would have been ashamed to receive alms, these men found out their wants, and supplied them secretly.

Now, although Cimon was so good and thoughtful, you must not imagine that it was always very easy for him to be so. It seems that when he was a young man he was very idle and lazy, and never thought of anything but his own pleasure.

Aristides the Just noticed how lazy and selfish the young man was, and one day went to see him. After a little talk, Aristides told him seriously that he ought to be ashamed of the life he was living, as it was quite unworthy of a good citizen or of a noble man.

This reproof was so just, that Cimon promised to do better, and tried so hard that he soon became one of the most industrious and unselfish men of his day.

Cimon was not the only rich man in Athens, however; for Pericles, another citizen, was even wealthier than he. As Pericles was shrewd, learned, and very eloquent, he soon gained much influence over his fellow-citizens.

While Cimon was generally seen in the company of men of his own class, and was hence considered the leader of the nobles or aristocrats, Pericles liked to talk with the poorer class, whom he could easily sway by his eloquent speeches, and who soon made him their idol.

Day by day the two parties became more distinct, and soon the Athenians sided either with Pericles or with Cimon in all important matters. The two leaders were at first very good friends, but little by little they drifted apart, and finally they became rivals.

About this time an earthquake brought great misfortunes upon Greece. The whole country shook and swayed, and the effects of the earthquake were so disastrous at Sparta that all the houses and temples were destroyed.

Many of the inhabitants were crushed under the falling stones and timbers, and there were only five houses left standing. The Spartans were in despair; and the Helots, or slaves, who had long been waiting for an opportunity to free themselves, fancied that the right time had come.

They quickly assembled, and decided to kill the Spartans while they were groping about among the ruined dwellings for the remains of their relatives and friends.

The plan would have succeeded had not the king, Archidamus, found it out. Without a moment's delay, he rallied all the able-bodied men, and sent a swift messenger to Athens for aid.

True to their military training, the Spartans dropped everything when the summons reached them; and the Helots came marching along, only to find their former masters drawn up in battle array, and as calm as if no misfortune had happened.

This unexpected resistance so frightened the Helots, that they hastily withdrew into Messenia. Here they easily persuaded the Messenians to join forces with them and declare war against the Spartans.

In the mean while the swift runner sent by Archidamus had reached Athens, and told about the destruction of the town and the perilous situation of the people. He ended by imploring the Athenians to send immediate aid, lest all the Spartans should perish.

Cimon, who was generous and kind-hearted, immediately cried out that the Athenians could not refuse to help their unhappy neighbors; but Pericles, who, like most of his fellow-citizens, hated the Spartans, advised all his friends to stay quietly at home.

Much discussion took place over this advice. At last, however, Cimon prevailed, and an army was sent to help the Spartans. Owing to the hesitation of the Athenians, this army came late, and they fought with so little spirit that the Lacedæmonians indignantly said that they might just as well have remained at home.

This insult so enraged the Athenians that they went home; and when it became publicly known how the Spartans had treated their army, the people began to murmur against Cimon. In their anger, they forgot all the good he had done them, and, assembling in the market place, they ostracized him.

The Age of Pericles

A

S

soon as Cimon had been banished, Pericles became sole leader of the Athenians; and as he governed them during a long and prosperous time, this period is generally known as the Age of Pericles.

The Spartans who had so rudely sent away their Athenian allies manfully resolved to help themselves, and set about it so vigorously that they soon brought the Helots back to order, and rebuilt their city. When they had settled themselves comfortably, however, they remembered the lukewarm help which had been given them, and determined to punish the Athenians.

The Persian general was just then planning a new invasion of Greece, so the Athenians found themselves threatened with a twofold danger. In their distress they recalled Cimon, who was an excellent general, and implored him to take command of their forces.

Cimon fully justified their confidence, and not only won several victories over the Spartans, but compelled them at last to agree to a truce of five years. This matter settled, he next attacked the Persians, whom he soon defeated by land and by sea.

He then forced Artaxerxes, the Persian king, to swear a solemn oath that he would never again wage war against the Athenians, and forbade the Persian vessels ever to enter the Ægean sea.

These triumphs won, Cimon died from the wounds he had received during the war. His death, however, was kept secret for a whole month, so that the people would have time to get used to a new leader, and not be afraid to fight without their former general.

While Cimon was thus successfully battling with the enemy abroad, Pericles had managed affairs at home. He urged the Athenians to finish their walls; and by his advice they built also the Long Walls, which joined the city to the Piræus, a seaport five miles away.

Pericles

Pericles also increased the Athenian navy, so that, by the time the five-years' truce was over, he had a fine fleet to use in fighting against the Spartans.

As every victory won by the Athenians had only made Sparta more jealous, the war was renewed, and carried on with great fury on both sides. The Spartans gained the first victories; but, owing to their better navy, the Athenians soon won over all the neighboring cities, and got the upper hand of their foes.

They were about to end the war by a last victory at Coronea, when fortune suddenly deserted them, and they were so sorely beaten that they were very glad to agree to a truce and return home.

By the treaty then signed, the Athenians bound themselves to keep the peace during a term of thirty years. In exchange, the Spartans allowed them to retain the cities which they had conquered, and the leadership of one of the confederacies formed by the Greek states, reserving the head of the other for themselves.

During these thirty years of peace, Pericles was very busy, and his efforts were directed for the most part toward the improvement of Athens. By his advice a magnificent temple, the Parthenon, was built on top of the Acropolis, in honor of Athene.

The Acropolis

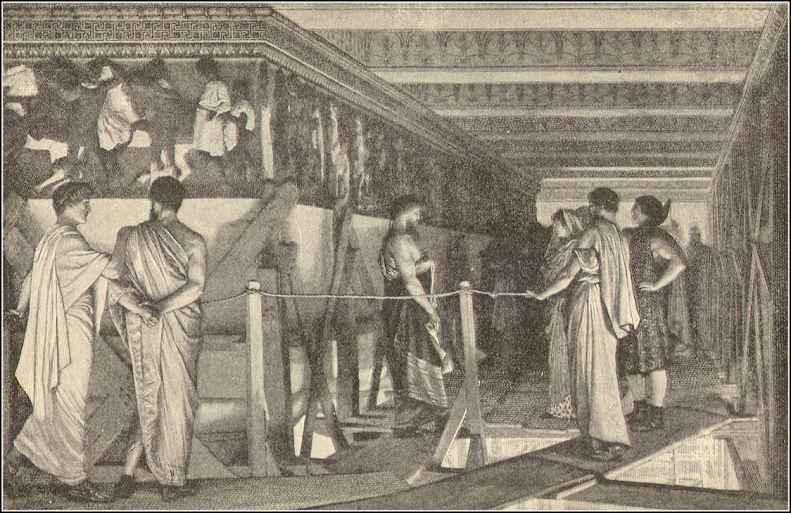

This temple, one of the wonders of the world, was decorated with beautiful carvings by Phidias, and all the rich Athenians went to see them as soon as they were finished. This sculptor also made a magnificent gold and ivory statue of the goddess to stand in the midst of the Parthenon. But in spite of all his talent, Phidias had many enemies. After a while they wrongfully accused him of stealing part of the gold intrusted to him. Phidias vainly tried to defend himself; but they would not listen to him, and put him in prison, where he died.

Phidias

Between the temple of Athene and the city there was a series of steps and beautiful porticoes, decorated with paintings and sculptures, which have never been surpassed.

Many other beautiful buildings were erected under the rule of Pericles; and the beauty and art loving Athenians could soon boast that their city was the finest in the world. Artists from all parts of the country thronged thither in search of work, and all were well received by Pericles.

The Teachings of Anaxagoras

A

S

Pericles was a very cultivated man, he liked to meet and talk with the philosophers, and to befriend the artists. He was greatly attached to the sculptor Phidias, and he therefore did all in his power to save him from the envy of his fellow-citizens.

Anaxagoras, a philosopher of great renown, was the friend and teacher of Pericles. He, too, won the dislike of the people; and, as they could not accuse him also of stealing, they charged him with publicly teaching that the gods they worshiped were not true gods, and proposed to put him to death for this crime.

Now, Anaxagoras had never heard of the true God, the God whom we worship. He had heard only of Zeus, Athene, and the other gods honored by his people; but he was so wise and so thoughtful that he believed the world could never have been created by such divinities as those.

He observed all he saw very attentively, and shocked the people greatly by saying that the sun was not a god driving in a golden chariot, but a great glowing rock, which, in spite of its seemingly small size, he thought must be about as large as the Peloponnesus.

Of course, this seems very strange to you. But Anaxagoras lived more than two thousand years ago, and since then people have constantly been finding out new things and writing them in books, so it is no wonder that in this matter you are already, perhaps, wiser than he. When you come to study about the sun, you will find that Anaxagoras was partly right, but that, instead of being only as large as the Peloponnesus, the sun is more than a million times larger than the whole earth!

Anaxagoras also tried to explain that the moon was probably very much like the earth, with mountains, plains, and seas. These things, which they could not understand, made the Athenians so angry that they exiled the philosopher, in spite of all Pericles could say.

Anaxagoras went away without making any fuss, and withdrew to a distant city, where he continued his studies as before. Many people regretted his absence, and missed his wise conversation, but none so much as Pericles, who never forgot him, and who gave him money enough to keep him in comfort.