The Story of the Greeks (Yesterday's Classics) (20 page)

As they did not even know the language of the country, they could not ask their way; and as they were surrounded by enemies, they must be constantly on their guard lest they should be surprised and taken prisoners or killed. They were indeed in a sorry plight; and no wonder that they all fancied they would never see their homes again. When night came on, they flung themselves down upon the ground without having eaten any supper. Their hearts were so heavy, however, that they could not sleep, but tossed and moaned in their despair.

In this army there was a pupil of Socrates, called Xenophon. He was a good and brave man. Instead of bewailing his bad luck, as the others did, he tried to think of some plan by which the army might yet be saved, and brought back to Greece.

His night of deep thought was not in vain; and as soon as morning dawned he called his companions together, and begged them to listen to him, as he had found a way of saving them from slavery or death.

Then he explained to them, that, if they were only united and willing, they could form a compact body, and, under a leader of their own choosing, could beat a safe retreat toward the sea.

The Retreat of the Ten Thousand

X

ENOPHON

'

S

advice pleased the Greeks. It was far better, they thought, to make the glorious attempt to return home, than basely to surrender their arms, and become the subjects of a foreign king.

They therefore said they would elect a leader, and all chose Xenophon to fill this difficult office. He, however, consented to accept it only upon condition that each soldier would pledge his word of honor to obey him; for he knew that the least disobedience would hinder success, and that in union alone lay strength. The soldiers understood this too, and not only swore to obey him, but even promised not to quarrel among themselves.

So the little army began its homeward march, tramping bravely over sandy wastes and along rocky pathways. When they came to a river too deep to be crossed by fording, they followed it up toward its source until they could find a suitable place to get over it; and, as they had neither money nor provisions, they were obliged to seize all their food on the way.

The Greeks not only had to overcome countless natural obstacles, but were also compelled to keep up a continual warfare with the Persians who pursued them. Every morning Xenophon had to draw up his little army in the form of a square, to keep the enemy at bay.

They would fight thus until nearly nightfall, when the Persians always retreated, to camp at a distance from the men they feared. Instead of allowing his weary soldiers to sit down and rest, Xenophon would then give orders to march onward. So they tramped in the twilight until it was too dark or they were too tired to proceed any farther.

After a hasty supper, the Greeks flung themselves down to rest on the hard ground, under the light of the stars; but even these slumbers were cut short by Xenophon's call at early dawn. Long before the lazy Persians were awake, these men were again marching onward; and when the mounted enemy overtook them once more, and compelled them to halt and fight, they were several miles nearer home.

As the Greeks passed though the wild mountain gorges they were further hindered by the neighboring people, who tried to stop them by rolling trunks of trees and rocks down upon them. Although some were wounded and others killed, the little army pressed forward, and, after a march of about a thousand miles, they came at last within sight of the sea.

You may imagine what a joyful shout arose, and how lovingly they gazed upon the blue waters which washed the shores of their native land also.

But although Xenophon and his men had come to the sea, their troubles were not yet ended; for, as they had no money to pay their passage, none of the captains would take them on board.

Instead of embarking, therefore, and resting their weary limbs while the wind wafted them home, they were forced to tramp along the seashore. They were no longer in great danger, but were tired and discontented, and now for the first time they began to forget their promise to obey Xenophon.

To obtain money enough to pay their passage to Greece, they took several small towns along their way, and robbed them. Then, hearing that there was a new expedition on foot to free the Ionian cities from the Persian yoke, they suddenly decided not to return home, but to go and help them.

Xenophon therefore led them to Pergamus, where he gave them over to their new leader. There were still ten thousand left out of the eleven thousand men that Cyrus had hired, and Xenophon had cause to feel proud of having brought them across the enemy's territory with so little loss.

After bidding them farewell, Xenophon returned home, and wrote down an account of this famous Retreat of the Ten Thousand in a book called the Anabasis. This account is so interesting that people begin to read it as soon as they know a little Greek, and thus learn all about the fighting and marching of those brave men.

Agesilaus in Asia

Y

OU

may remember that the Greeks, at the end of the Peloponnesian War, had found out that Sparta was the strongest city in the whole country; for, although the Athenians managed to drive the Spartans out of their city, they were still forced to recognize them as the leaders of all Greece.

The Spartans were proud of having reached such a position, and were eager to maintain it at any cost. They therefore kept all the Greek towns under their orders, and were delighted to think that their king, Agesilaus, was one of the best generals of his day.

He was not, however, tall and strong, like most of his fellow-citizens, but puny and very lame. His small size and bad health had not lessened his courage, however, and he was always ready to plan a new campaign or to lead his men off to war.

When it became known that Artaxerxes was about to march against the Greek cities in Ionia, to punish them for upholding his brother Cyrus, and for sending him the ten thousand soldiers who had beat such a masterly retreat, Agesilaus made up his mind to go and help them.

There was no prospect of fighting at home just then, so the Spartan warriors were only too glad to follow their king to Asia. Agesilaus had no sooner landed in Asia Minor, than the Greeks cities there gave him command over their army, bidding him defend them from the wrath of Artaxerxes.

Now, although the Persian host, as usual, far outnumbered the Greek army, Agesilaus won several victories over his enemies, who were amazed that such a small and insignificant-looking man should be at the same time a king and a great general.

They were accustomed to so much pomp and ceremony, and always saw their own king so richly dressed, that it seemed very queer to them to see Agesilaus going about in the same garments as his men, and himself leading them in battle.

A Strange Interview

W

E

are told that Agesilaus was once asked to meet the Persian general Pharnabazus, to have a talk or conference with him,—a thing which often took place between generals of different armies.

The meeting was set for a certain day and hour, under a large tree, and it was agreed that both generals should come under the escort of their personal attendant only.

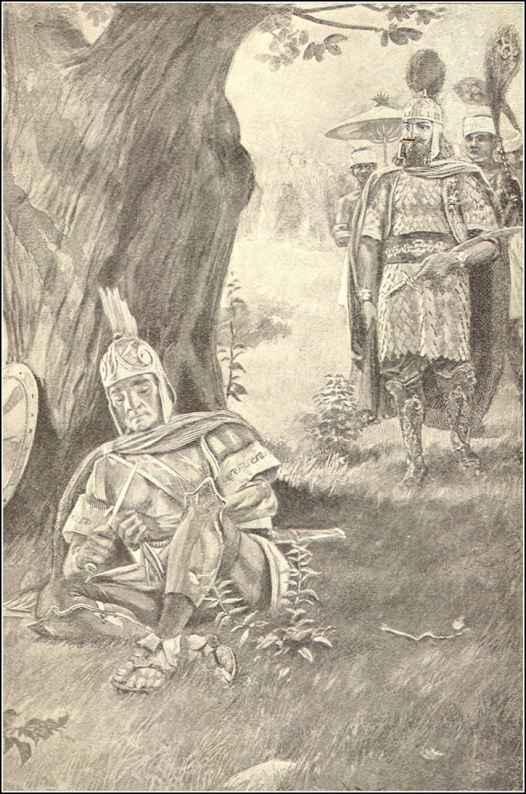

Agesilaus, plainly clad as usual, came first to the meeting place, and, sitting down upon the grass under the tree, he began to eat his usual noonday meal of bread and onions.

A few moments later the Persian general arrived in rich attire, attended by fan and parasol bearer, and by servants bringing carpets for him to sit upon, cooling drinks to refresh him, and delicate dishes to tempt his appetite.

At first Pharnabazus fancied that a tramp was camping under the tree; but when he discovered that this plain little man was really Agesilaus, King of Sparta, and the winner of so many battles, he was ashamed of his pomp, sent away his attendants, and sat down on the ground beside the king.

Agesilaus and Pharnabazus

They now began an important talk, and Pharnabazus was filled with admiration when he heard the short but noble answers which Agesilaus had for all his questions. He was so impressed by the Spartan king, that he shook hands with him when the interview was ended.

Agesilaus was equally pleased with Pharnabazus, and told him that he should be proud to call him friend. He invited him to leave his master, and come and live in Greece where all noble men were free.

Pharnabazus did not accept this invitation, but renewed the war, whereupon Agesilaus again won several important victories. When the Persian king heard that all his soldiers could not get the better of the Spartan king, he resolved to try the effect of bribery.

He therefore sent a messenger to Athens to promise this city and her allies a very large sum of money provided that they would rise up in revolt against Sparta, and thus force Agesilaus to come home.

The Peace of Antalcidas

T

HE

Athenians hated the Spartans, and were only waiting for an excuse to make war against them: so they were only too glad to accept the bribe which Artaxerxes offered, and were paid with ten thousand Persian coins on which was stamped the figure of an archer.

As soon as the Spartan ephors heard that the Athenians had revolted, they sent a message to Agesilaus to tell him to come home. The Spartan king was about to deal a crushing blow to the Persians, but he was forced to obey the summons. As he embarked he dryly said, "I could easily have beaten the whole Persian army, and still ten thousand Persian archers have forced me to give up all my plans.

The Thebans joined the Athenians in this revolt, so Agesilaus was very indignant against them too. He energetically prepared for war, and met the combined Athenian and Theban forces at Coronea, where he defeated them completely.

The Athenians, in the mean while, had made their alliance with the Persians, and used the money which they had received to strengthen their ramparts, as you have seen, and to finish the Long Walls, which had been ruined by the Spartans ten years before.

All the Greek states were soon in arms, siding with the Athenians or with the Spartans; and the contest continued until everybody was weary of fighting. There was, besides, much jealousy among the people themselves, and even the laurels of Agesilaus were envied.

The person who was most opposed to him was the Spartan Antalcidas, who, fearing that further warfare would only result in increasing Agesilaus' popularity and glory, now began to advise peace. As the Greeks were tired of the long struggle, they sent Antalcidas to Asia to try to make a treaty with the Persians.

Without thinking of anything but his hatred of Agesilaus, Antalcidas consented to all that the Persians asked, and finally signed a shameful treaty, by which all the Greek cities of Asia Minor and the Island of Cyprus were handed over to the Persian king. The other Greek cities were declared independent, and thus Sparta was shorn of much of her power. This treaty was a disgrace, and it has always been known in history by the name of the man who signed it out of petty spite.

The Theban Friends

A

LTHOUGH

all the Greek cities were to be free by the treaty of Antalcidas, the Spartans kept the Messenians under their sway; and, as they were still the most powerful people in Greece, they saw that the other cities did not infringe upon their rights in any way.

Under pretext of keeping all their neighbors in order, the Spartans were always under arms, and on one occasion even forced their way into the city of Thebes. The Thebans, who did not expect them, were not ready to make war, and were in holiday dress.

They were all in the temple, celebrating the festival of Demeter, the harvest goddess; and when the Spartans came thus upon them, they were forced to yield without striking a single blow, as they had no weapons at hand.

The Spartans were so afraid lest the best and richest citizens should try to make the people revolt, that they exiled them all from Thebes, allowing none but the poor and insignificant to remain.

To keep possession of the city which they had won by this trick, the Spartans put three thousand of their best warriors in the citadel, with orders to defend and hold it at any price.

Among the exiled Thebans there was a noble and wealthy man called Pelopidas. He had been sorely wounded in a battle some time before, and would have died had he not been saved by a fellow-citizen named Epaminondas, who risked his own life in the rescue.

This man, too, was of noble birth, and was said to be a descendant of the men who had sprung from the dragon teeth sown by Cadmus, the founder of Thebes. Epaminondas however, was very poor; and wealth had no charms for him, for he was a disciple of Pythagoras, a philosopher who was almost as celebrated as Socrates.

Now, although Epaminondas was poor, quiet, and studious, and Pelopidas was particularly fond of noise and bustle, they became great friends and almost inseparable companions. Pelopidas, seeing how good and generous a man his friend was, did all he could to be like him, and even gave up all his luxurious ways to live plainly too.