The Summer Book (2 page)

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #Fiction, #Family Life, #Literary, #Biographical

Photographs on following pages:

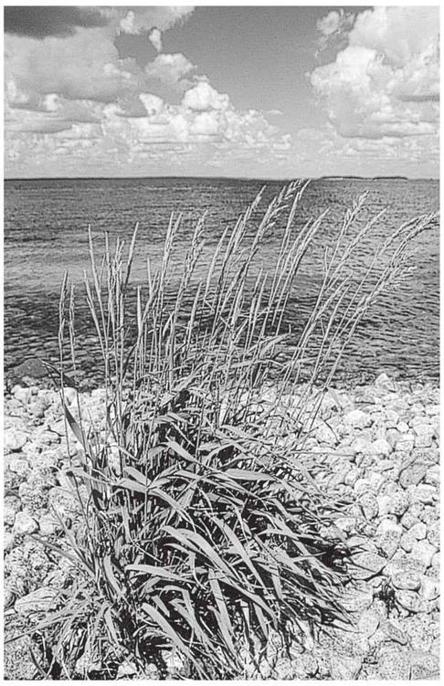

Page 15:

The summer island.

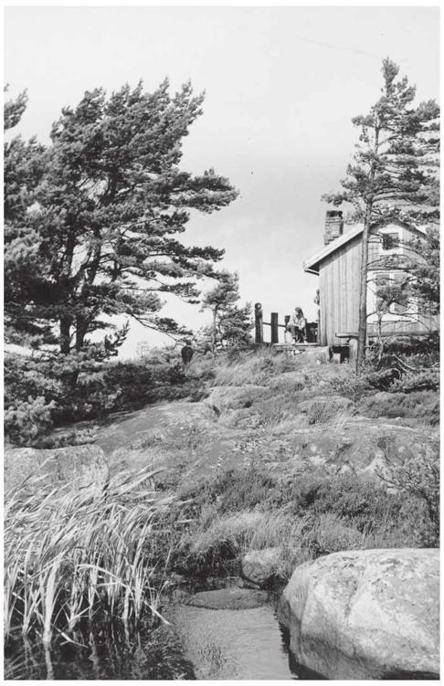

Page 16:

Tove Jansson beside the home she and her brother, Lars, built on the island.

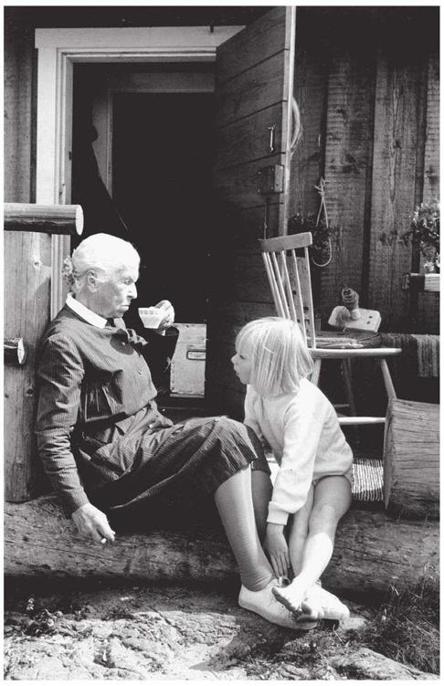

Page 17:

Tove Jansson’s mother, Signe Hammarsten, and niece, Sophia Jansson; they shared many summers on the island and were the inspiration behind the book’s two main characters.

The

Summer

Book

T

OVE

J

ANSSON

The Morning Swim

I

T WAS AN EARLY, VERY WARM MORNING IN

J

ULY

, and it had rained during the night. The bare granite steamed, the moss and crevices were drenched with moisture, and all the colours everywhere had deepened. Below the veranda, the vegetation in the morning shade was like a rainforest of lush, evil leaves and flowers, which she had to be careful not to break as she searched. She held one hand in front of her mouth and was constantly afraid of losing her balance.

“What are you doing?” asked little Sophia.

“Nothing,” her grandmother answered. “That is to say,” she added angrily, “I’m looking for my false teeth.”

The child came down from the veranda. “Where did you lose them?” she asked.

“Here,” said her grandmother. “I was standing right there and they fell somewhere in the peonies.” They looked together.

“Let me,” Sophia said. “You can hardly walk. Move over.”

She dived beneath the flowering roof of the garden and crept among green stalks and stems. It was pretty and mysterious down on the soft black earth. And there were the teeth, white and pink, a whole mouthful of old teeth.

“I’ve got them!” the child cried, and stood up. “Put them in.”

“But you can’t watch,” Grandmother said. “That’s private.”

Sophia held the teeth behind her back.

“I want to watch,” she said.

So Grandmother put the teeth in, with a smacking noise. They went in very easily. It had really hardly been worth mentioning.

“When are you going to die?” the child asked.

And Grandmother answered, “Soon. But that is not the least concern of yours.”

“Why?” her grandchild asked.

She didn’t answer. She walked out on the rock and on towards the ravine.

“We’re not allowed out there!” Sophia screamed.

“I know,” the old woman answered disdainfully. “Your father won’t let either one of us go out to the ravine, but we’re going anyway, because your father is asleep and he won’t know.”

They walked across the granite. The moss was slippery. The sun had come up a good way now, and everything was steaming. The whole island was covered with a bright haze. It was very pretty.

“Will they dig a hole?” asked the child amiably.

“Yes,” she said. “A big hole.” And she added, insidiously, “Big enough for all of us.”

“How come?” the child asked.

They walked on towards the point.

“I’ve never been this far before,” Sophia said. “Have you?”

“No,” her grandmother said.

They walked all the way out onto the little promontory, where the rock descended into the water in terraces that became fainter and fainter until there was total darkness. Each step down was edged with a light green seaweed fringe that swayed back and forth with the movement of the sea.

“I want to go swimming,” the child said. She waited for opposition, but none came. So she took off her clothes, slowly and nervously. She glanced at her grandmother – you can’t depend on people who just let things happen. She put her legs in the water.

“It’s cold,” she said.

“Of course it’s cold,” the old woman said, her thoughts somewhere else. “What did you expect?”

The child slid in up to her waist and waited anxiously.

“Swim,” her grandmother said. “You can swim.”

It’s deep, Sophia thought. She forgets I’ve never swum in deep water unless somebody was with me. And she climbed out again and sat down on the rock.

“It’s going to be a nice day today,” she declared.

The sun had climbed higher. The whole island, and the sea, were glistening. The air seemed very light.

“I can dive,” Sophia said. “Do you know what it feels like when you dive?”

“Of course I do,” her grandmother said. “You let go of everything and get ready and just dive. You can feel the seaweed against your legs. It’s brown, and the water’s clear, lighter towards the top, with lots of bubbles. And you glide. You hold your breath and glide and turn and come up, let yourself rise and breathe out. And then you float. Just float.”

“And all the time with your eyes open,” Sophia said.

“Naturally. People don’t dive with their eyes shut.”

“Do you believe I can dive without me showing you?” the child asked.

“Yes, of course,” Grandmother said. “Now get dressed. We can get back before he wakes up.”

The first weariness came closer. When we get home, she thought, when we get back I think I’ll take a little nap. And I must remember to tell him this child is still afraid of deep water.

Moonlight

O

NE TI ME IN

A

PRIL THERE WAS A FULL MOON

, and the sea was covered with ice. Sophia woke up and remembered that they had come back to the island and that she had a bed to herself because her mother was dead. The fire was still burning in the stove, and the flames flickered on the ceiling, where the boots were hung up to dry. She climbed down to the floor, which was very cold, and looked out through the window.

The ice was black, and in the middle of the ice she saw the open stove door and the fire – in fact she saw two stove doors, very close together. In the second window, the two fires were burning underground, and through the third window she saw a double reflection of the whole room, trunks and chests and boxes with gaping lids. They were filled with moss and snow and dry grass, all of them open, with bottoms of coal-black shadow. She saw two children out on the rock, and there was a rowan tree growing right through them. The sky behind them was dark blue.

She lay down in her bed and looked at the fire dancing on the ceiling, and all the time the island seemed to be coming closer and closer to the house. They were sleeping by a meadow near the shore, with patches of snow on the covers, and under them the ice darkened and began to glide. A channel opened very slowly in the floor, and all their luggage floated out in the river of moonlight. All the suitcases were open and full of darkness and moss, and none of them ever came back.

Sophia reached out her hand and pulled her grandmother’s plait, very gently. Grandmother woke up instantly.

“Listen,” Sophia whispered. “I saw two fires in the window. Why are there two fires instead of one?”

Her grandmother thought for a moment and said, “It’s because we have double windows.”

After a while Sophia asked, “Are you sure the door is closed?”

“It’s open,” her grandmother said. “It’s always open; you can sleep quite easy.”

Sophia rolled up in the quilt. She let the whole island float out on the ice and on to the horizon. Just before she fell asleep, her father got up and put more wood in the stove.

The Magic Forest

O

N THE OUTSIDE OF THE ISLAND

, beyond the bare rock, there was a stand of dead forest. It lay right in the path of the wind and for many hundreds of years had tried to grow directly into the teeth of every storm, and had thus acquired an appearance all its own. From a passing boat it was obvious that each tree was stretching away from the wind; they crouched and twisted, and many of them crept. Eventually the trunks broke or rotted and then sank, the dead trees supporting or crushing those still green at the top. All together they formed a tangled mass of stubborn resignation. The ground was shiny with brown needles, except where the spruces had decided to crawl instead of stand, their greenery luxuriating in a kind of frenzy, damp and glossy as if in a jungle.

This forest was called “the magic forest”. It had shaped itself with slow and laborious care, and the balance between survival and extinction was so delicate that even the smallest change was unthinkable. To open a clearing or separate the collapsing trunks might lead to the ruin of the magic forest. The marshy spots could not be drained, and nothing could be planted behind the dense, sheltering wall of trees. Deep under this thicket, in places where the sun never shone, there lived birds and small animals. In calm weather you could hear the rustle of wings and hastily scurrying feet, but the animals never showed themselves.

In the beginning, the family tried to make the magic forest more terrible than it was. They collected stumps and dry juniper bushes from neighbouring islands and rowed them back to the forest. Huge specimens of weathered, whitened beauty were dragged across the island. They splintered and cracked and made broad, empty paths to the places where they were to stand. Grandmother could see that it wasn’t turning out right, but she said nothing. Afterwards, she cleaned the boat and waited until the rest of the family tired of the magic forest. Then she went in by herself. She crawled slowly past the marsh and the ferns, and when she got tired she lay down on the ground and looked up through the network of grey lichens and branches. Later, the others asked her where she had been, and she replied that maybe she had slept a little while.

Except for the magic forest, the island became an orderly, beautiful park. They tidied it down to the smallest twig while the earth was still soaked with spring rain, and, after that, they stuck carefully to the narrow paths that wandered through the carpet of moss from one granite outcropping to another and down to the sand beach. Only farmers and summer guests walk on the moss. What they don’t know – and it cannot be repeated too often – is that moss is terribly frail. Step on it once and it rises the next time it rains. The second time, it doesn’t rise back up. And the third time you step on moss, it dies. Eider ducks are the same way – the third time you frighten them up from their nests, they never come back. Sometime in July the moss would adorn itself with a kind of long, light grass. Tiny clusters of flowers would open at exactly the same height above the ground and sway together in the wind, like inland meadows, and the whole island would be covered with a veil dipped in heat, hardly visible and gone in a week. Nothing could give a stronger impression of untouched wilderness.

Grandmother sat in the magic forest and carved outlandish animals. She cut them from branches and driftwood and gave them paws and faces, but she only hinted at what they looked like and never made them too distinct. They retained their wooden souls, and the curve of their backs and legs had the enigmatic shape of growth itself and remained a part of the decaying forest. Sometimes she cut them directly out of a stump or the trunk of a tree.

Her carvings became more and more numerous. They clung to trees or sat astride the branches, they rested against the trunks or settled into the ground. With outstretched arms, they sank in the marsh, or they curled up quietly and slept by a root. Sometimes they were only a profile in the shadows, and sometimes there were two or three together, entwined in battle or in love. Grandmother worked only in old wood that had already found its form. That is, she saw and selected those pieces of wood that expressed what she wanted them to say.