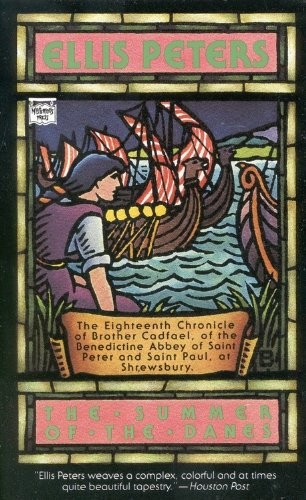

The Summer of the Danes

Read The Summer of the Danes Online

Authors: Ellis Peters

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General

The

Summer

of the Danes

The Eighteenth

Chronicle of Brother Cadfael, of the Benedictine Abbey of Saint Peter and Saint

Paul, at Shrewsbury

Ellis Peters

THE

EXTRAORDINARY EVENTS OF THAT SUMMER of 1144 may properly be said to have begun

the previous year, in a tangle of threads both ecclesiastical and secular, a

net in which any number of diverse people became enmeshed, clerics, from the

archbishop down to Bishop Roger de Clinton’s lowliest deacon, and the laity

from the princes of North Wales down to the humblest cottager in the trefs of

Arfon. And among the commonalty thus entrammelled, more to the point, an

elderly Benedictine monk of the Abbey of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, at

Shrewsbury. Brother Cadfael had approached that April in a mood of slightly

restless hopefulness, as was usual with him when the birds were nesting, and

the meadow flowers just beginning to thrust their buds up through the new

grass, and the sun to rise a little higher in the sky every noon. True, there

were troubles in the world, as there always had been. The vexed affairs of

England, torn in two by two cousins contending for the throne, had still no

visible hope of a solution. King Stephen still held his own in the south and

most of the east; the Empress Maud, thanks to her loyal half-brother, Robert of

Gloucester, was securely established in the southwest and maintained her own

court unmolested in Devizes. But for some months now there had been very little

fighting between them, whether from exhaustion or policy, and a strange calm

had settled over the country, almost peace. In the Fens the raging outlaw Geoffrey

de Mandeville, every man’s enemy, was still at liberty, but a liberty

constricted by the king’s new encircling fortresses, and increasingly

vulnerable. All in all, there was room for some cautious optimism, and the very

freshness and lustre of the spring forbade despondency, even had despondency

been among Cadfael’s propensities. So he came to chapter, on this particular

day at the end of April, in the most serene and acquiescent of spirits, full of

mild good intentions towards all men, and content that things should continue

as bland and uneventful through the summer and into the autumn. He certainly

had no premonition of any immediate change in this idyllic condition, much less

of the agency by which it was to come.

As

though compelled, half fearfully and half gratefully, to the same precarious

but welcome quietude, the business at chapter that day was modest and aroused

no dispute, there was no one in default, not even a small sin among the novices

for Brother Jerome to deplore, and the schoolboys, intoxicated with the spring

and the sunshine, seemed to be behaving like the angels they certainly were

not. Even the chapter of the Rule, read in the flat, deprecating tones of

Brother Francis, was the 34

th

, gently explaining that the doctrine

of equal shares for all could not always be maintained, since the needs of one

might exceed the needs of another, and he who received more accordingly must

not preen himself on being supplied beyond his brothers, and he that received

less but enough must not grudge the extra bestowed on his brothers. And above

all, no grumbling, no envy. Everything was placid, conciliatory, moderate.

Perhaps, even, a shade on the dull side?

It

is a blessed thing, on the whole, to live in slightly dull times, especially

after disorder, siege and bitter contention. But there was still a morsel

somewhere in Cadfael that itched if the hush continued too long. A little

excitement, after all, need not be mischief, and does sound a pleasant

counterpoint to the constant order, however much that may be loved and however

faithfully served.

They

were at the end of routine business, and Cadfael’s attention had wandered away

from the details of the cellarer’s accounts, since he himself had no function

as an obedientiary, and was content to leave such matters to those who had.

Abbot Radulfus was about to close the chapter, with a sweeping glance around

him to make sure that no one else was brooding over some demur or reservation,

when the lay porter who served at the gatehouse during service or chapter put

his head in at the door, in a manner which suggested he had been waiting for

this very moment, just out of sight.

“Father

Abbot, there is a guest here from Lichfield. Bishop de Clinton has sent him on

an errand into Wales, and he asks lodging here for a night or two.”

Anyone

of less importance, thought Cadfael, and he would have let it wait until we all

emerged, but if the bishop is involved it may well be serious business, and

require official consideration before we disperse. He had good memories of Roger

de Clinton, a man of decision and solid good sense, with an eye for the genuine

and the bogus in other men, and a short way with problems of doctrine. By the

spark in the abbot’s eye, though his face remained impassive, Radulfus also

recalled the bishop’s last visit with appreciation.

“The

bishop’s envoy is very welcome,” he said, “and may lodge here for as long as he

wishes. Has he some immediate request of us, before I close this chapter?”

“Father,

he would like to make his reverence to you at once, and let you know what his

errand is. At your will whether it should be here or in private.”

“Let

him come in,” said Radulfus.

The

porter vanished, and the small, discreet buzz of curiosity and speculation that

went round the chapterhouse like a ripple on a pond ebbed into anticipatory

silence as the bishop’s envoy came in and stood among them.

A

little man, of slender bones and lean but wiry flesh, diminutive as a

sixteen-year-old boy, and looking very much like one, until discerning

attention discovered the quality and maturity of the oval, beardless face. A

Benedictine like these his brothers, tonsured and habited, he stood erect in

the dignity of his office and the humility and simplicity of his nature, as

fragile as a child and as durable as a tree. His straw-coloured ring of cropped

hair had an unruly spikiness, recalling the child. His grey eyes, formidably

direct and clear, confirmed the man.

A

small miracle! Cadfael found himself suddenly presented with a gift he had

often longed for in the past few years, by its very suddenness and

improbability surely miraculous. Roger de Clinton had chosen as his accredited

envoy into Wales not some portly canon of imposing presence, from the inner

hierarchy of his extensive see, but the youngest and humblest deacon in his

household, Brother Mark, sometime of Shrewsbury abbey, and assistant for two

fondly remembered years among the herbs and medicines of Cadfael’s workshop.

Brother Mark made a deep reverence to the abbot, dipping his ebullient tonsure

with a solemnity which still retained, until he lifted those clear eyes again,

the slight echo and charm of absurdity which had always clung about the mute

waif Cadfael first recalled. When he stood erect he was again the ambassador;

he would always be both man and child from this time forth, until the day when

he became priest, which was his passionate desire. And that could not be for

some years yet, he was not old enough to be accepted.

“My

lord,” he said, “I am sent by my bishop on an errand of goodwill into Wales. He

prays you receive and house me for a night or two among you.”

“My

son,” said the abbot, smiling, “you need here no credentials but your presence.

Did you think we could have forgotten you so soon? You have here as many

friends as there are brothers, and in only two days you will find it hard to

satisfy them all. And as for your errand, or your lord’s errand, we will do all

we can to forward it. Do you wish to speak of it? Here, or in private?”

Brother

Mark’s solemn face melted into a delighted smile at being not only remembered,

but remembered with obvious pleasure. “It is no long story, Father,” he said,

“and I may well declare it here, though later I would entreat your advice and

counsel, for such an embassage is new to me, and there is no one could better

aid me to perform it faithfully than you. You know that last year the Church

chose to restore the bishopric of Saint Asaph, at Llanelwy.”

Radulfus

agreed, with an inclination of his head. The fourth Welsh diocese had been in

abeyance for some seventy years, very few now living could remember when there

had been a bishop on the throne of Saint Kentigern. The location of the see,

with a foot either side the border, and all the power of Gwynedd to westward,

had always made it difficult to maintain. The cathedral stood on land held by

the earl of Chester, but all the Clwyd valley above it was in Owain Gwynedd’s

territory. Exactly why Archbishop Theobald had resolved on reviving the diocese

at this time was not quite clear to anyone, perhaps not even the archbishop.

Mixed motives of Church politics and secular manoeuvring apparently required a

firmly English hold on this borderland, for the appointed man was a Norman.

There was not much tenderness towards Welsh sensitivities in such a preferment,

Cadfael reflected ruefully.

“And

after his consecration last year by Archbishop Theobald, at Lambeth, Bishop

Gilbert is finally installed in his see, and the archbishop wishes him to

receive assurance he has the support of our own bishop, since the pastoral

duties in those parts formerly rested in the diocese of Lichfield. I am the

bearer of letters and gifts to Llanelwy on my lord’s behalf.”

That

made sense, if the whole intent of the Church was to gain a firm foothold well

into Welsh land, and demonstrate that it would be preserved and defended. A

marvel, Cadfael considered, that any bishop had ever contrived to manage so

huge a see as the original bishopric of Mercia, successively shifting its base

from Lichfield to Chester, back again to Lichfield, and now to Coventry, in the

effort to remain in touch with as diverse a flock as ever shepherd tended. And

Roger de Clinton might not be sorry to be quit of those border parishes,

whether or not he approved the strategy which deprived him of them.

“The

errand that brings you back to us, even for a few days, is dearly welcome,”

said Radulfus. “If my time and experience can be of any avail to you, they are

yours, though I think you are equipped to acquit yourself well without any help

from me or any man.”

“It

is a weighty honour to be so trusted,” said Mark very gravely.

“If

the bishop has no doubts,” said Radulfus, “neither need you. I take him for a

man who can judge very well where to place his trust. If you have ridden from

Lichfield you must be in need of some rest and refreshment, for it’s plain you

set out early. Is your mount being cared for?”

“Yes,

Father.” The old address came back naturally.

“Then

come with me to my lodging, and take some ease, and use my time as you may

wish. What wisdom I have is at your disposal.” He was already acutely aware, as

Cadfael was, that this apparently simple mission to the newly made and alien

bishop at Saint Asaph covered a multitude of other calculated risks and

questionable issues, and might well send this wise innocent feeling his way

foot by foot through a quagmire, with quaking turf on every hand. All the more

impressive, then, that Roger de Clinton had placed his faith in the youngest

and least of his attendant clerics.

“This

chapter is concluded,” said the abbot, and led the way out. As he passed the

visitor by, Brother Mark’s grey eyes, at liberty at last to sweep the assembly

for other old friends, met Cadfael’s eyes, and returned his smile, before the

young man turned and followed his superior. Let Radulfus have him for a while,

savour him, get all his news from him, and all the details that might

complicate his coming journey, give him the benefit of long experience and

unfailing commonsense. Later on, when that was done, Mark would find his own

way back to the herb garden.