The Sun and the Moon: The Remarkable True Account of Hoaxers, Showmen, Dueling Journalists, and Lunar Man-Bats in Nineteenth-Century New York (25 page)

Authors: Matthew Goodman

– 145 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 146

the sun and the moon

encouraging a public fascination with astronomy that would culminate with the appearance of Halley’s Comet, which Sir John had predicted for September or October 1835. The growing interest in astronomy had not gone unnoticed by the new editor of the

Sun,

Richard Adams Locke, who was, like so many scientifically minded people, an admirer of Sir John Herschel. As one who kept up with all the latest astronomical reports, Locke was well aware that Sir John was presently working at the Cape of Good Hope—a spot so distant that a letter sent there would require months for a reply—and that the world still awaited, with great anticipation, the news of his latest discoveries.

– 146 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 147

c h a p t e r

9

A Passage to

the Moon

Among the other Americans who read John Herschel’s

A Treatise on

Astronomy

in 1834 was a young short-story writer in Baltimore named Edgar Allan Poe. Like Richard Adams Locke, Poe was a longtime astronomy buff and he read Herschel’s book with great interest, paying special attention to its discussion of the possibility of future explorations of the moon; as he later wrote in his essay on Locke in

The Literati of

New York City,

it was a theme that “excited my fancy.” Having finished

A Treatise on Astronomy,

Poe decided to create a moon story of his own, which he called “Hans Phaall—A Tale.” While John Herschel was not the protagonist of “Hans Phaall,” his book was its inspiration, and indeed provided the text for many of the story’s scientific passages (a fact that Poe would never reveal). “Hans Phaall” was published at the beginning of the summer of 1835, and Locke’s

Great Astronomical Discoveries

at the end. Two moon stories appearing only two months apart, each one involving John Herschel—the coincidence seemed to Poe so unlikely that for years he insisted that his story had been plagiarized by Richard Adams Locke. Poe found it even more galling that Locke’s story had achieved international renown, while his—which he considered far more deserving— languished in obscurity. It was, for Poe, one more reason to despise the literary world, yet another defeat in a life full of reversals.

In 1834 Edgar Allan Poe was living in a little brick house on Amity Street with his aunt Maria Clemm and his twelve-year-old cousin Virginia, whom he would marry shortly after she turned thirteen. He was a most

– 147 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 148

the sun and the moon

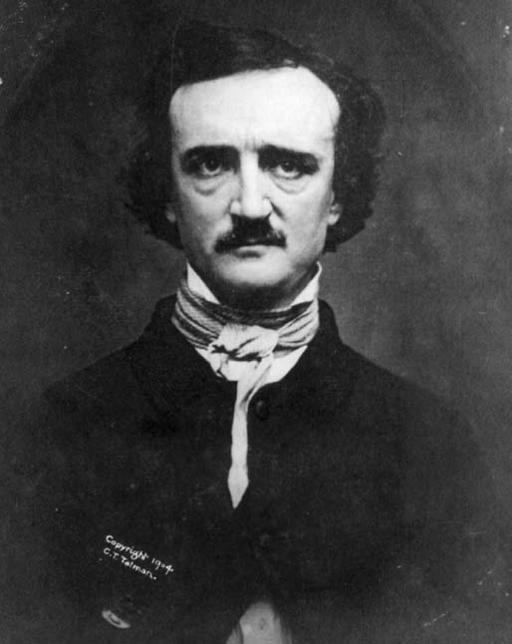

“The Bard”: Edgar Allan Poe, in a rare photograph taken near the

end of his life.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

incongruous figure—a moody, half-starved writer haunting the cheerful streets of Baltimore, a city that one guidebook of the time called “conspicuous, as well as for the rapidity of its growth, as for its present splen-dour and prosperity.” Broad avenues sloped down to the harbor, where steamers and schooners and clippers unloaded their wares into tidy brick warehouses stacked together as tightly as crates; the city’s markets were abundantly supplied with fresh local food, including the much-celebrated blue crabs and oysters pulled from the waters of the Chesapeake. To the north stood the tall steeple of St. Paul’s and the grand marble column of the Washington Monument, surmounted by a statue of the Father of the Country himself, who seemed to gaze in approval over the picturesque city below.

– 148 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 149

A Passage to the Moon

Those proud edifices of church and state, however, held little interest for Edgar Allan Poe. He preferred the clutter of E. J. Coale’s bookstore on Calvert Street, which carried the latest foreign books and magazines, or the hush of the library on Fayette Street, where he could read volumes of poetry or science without having to buy anything; or, when a few coins jingled in his pocket, Widow Meagle’s Oyster Parlor on Pratt Street, where in the evenings, by the warmth of the fire, he liked to recite his own poems—his voice, everyone remarked, had a pleasing, almost musical quality—the performances earning him a sobriquet from the other patrons that he must have cherished: “the Bard.” He wore linen shirts with Byron collars and a nattily tied black stock, a black double-vested waist-coat buttoned tight across his chest, over it a black frock coat (all of his clothes were old but still dapper, carefully mended and regularly brushed for him by his aunt), his long, silky black hair combed back over his ears, looking every inch the magnificent poet he believed himself to be. He was as proud a man as could be found in the city, an aristocrat in manner if no longer in means. Once he had lived in a large house surrounded by fig trees and raspberry bushes, his needs attended to by his stepfather’s black servants, but those days were long gone. The prosperous Richmond merchant John Allan, bowing to his wife’s pleas, had taken in the two-year-old orphan Edgar Poe, and for a time he had provided well for the boy, but as the years passed their relationship had grown increasingly bitter, fouled by resentment and misunderstanding. In 1834 John Allan died, leaving behind eight houses and an estate worth three-quarters of a million dollars, but to Edgar, living on the brink of starvation, he gave not a penny. For the rest of his life Poe would sign his work simply E. A. Poe or Edgar A. Poe, expunging from print the name he had inherited, with so little else, from his stepfather.

He had endured, by then, so many losses. His mother Eliza, a highly praised actress, had died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty-four, orphaning three children under five years old. By that time his father David Poe, also an actor (though by all accounts a far less winning one than his wife), had deserted the family, not to be heard from again. Later there would be two other women, one his stepmother and the other the mother of a friend, each of whom provided him much-needed maternal devotion, and each of whom died young. More recently his older brother Henry, arrived from Richmond to live with the Clemms in Baltimore, had died of tuberculosis while Edgar cared for him in the room

– 149 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 150

the sun and the moon

they shared. (His beloved Virginia would eventually succumb to the same disease; she died, as had his mother, at the age of twenty-four.) “I think I have already had my share of trouble for one so young,” he wrote once in a letter to John Allan.

In 1834 Edgar Allan Poe was already twenty-five, but despite all his furious exertions his life had amounted to little. He had been a fine student at the newly founded University of Virginia, but John Allan had with-drawn him after only a year there; Allan had refused to provide sufficient funds to cover his school expenses, and during the year Poe had accumulated more than two thousand dollars in gambling debts, in the misguided hope that he might win enough to pay off what he owed. After leaving the university he had returned to Richmond to stay at John Allan’s house, but after two months of conflict—the endless rehashing of grievances: the stinginess of the older man, the ingratitude of the younger—he fled in rage, his only plan for the future to be free of his stepfather’s supervision.

“My determination is at length taken,” he wrote in a letter he left for Allan—“to leave your house and endeavor to find some place in the wide world, where I will be treated—not as

you

have treated me.” He gave the address of a nearby tavern to which he requested that Allan send his clothes and books and enough money to pay for travel to a northern city, where he might start over. He hoped, he said, that Allan would comply with his requests “if you still have the least affection for me,” but Allan wrote back only to dismiss them: “After such a list of black charges,” he remarked sarcastically, “you Tremble for the consequence unless I send you a supply of money.” Two days later Poe wrote his stepfather again, the combative tone of the earlier letter replaced now by frank desperation: “I am in the greatest necessity, not having tasted food since Yesterday morning. I have no where to sleep at night, but roam about the Streets— I am nearly exhausted—I beseech you. . . . I have not one cent in the world to provide any food.” To this plea for help Poe received no response; having finished reading it John Allan turned over the page and scrawled on the back a single mocking retort: “Pretty Letter.”

Poe’s disappearance in the ensuing weeks has given rise to various legends, among them accounts of extended drinking bouts, of having his portrait painted by Henry Inman in London, even of his boarding a schooner to Greece—in the fashion of his hero Lord Byron—to help in the fight for national independence. In fact Poe did talk his way onto a ship, not a schooner but a coal barge, and bound not for Greece but for Boston.

– 150 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 151

A Passage to the Moon

Boston was a city that had always held great meaning for him, for it was where he had been born and where his mother had given some of her greatest performances, including acclaimed turns as Ophelia and Juliet; he still had the little watercolor she had painted of Boston Harbor, which she had left to him with the inscription, “For my little son Edgar, who should ever love Boston, the place of his birth, and where his mother found her

best,

and

most sympathetic

friends.” In Boston he managed to obtain occasional work as a clerk, but nothing that might sustain him. (What little money he had he used to publish his first volume of poetry,

Tamerlane and

Other Poems,

a forty-page booklet bound simply in paper, its author named only as “A Bostonian”; not surprisingly, the unassuming-looking little book received no critical attention.) After several fruitless months in Boston, hungry and exhausted and not knowing where else to turn, Edgar Allan Poe did what so many other poor young men with few prospects have done: he enlisted in the army.

Stationed first in Boston and then at various forts in the South, Poe distinguished himself in the military as he had in school. He rose quickly through the ranks, eventually earning a promotion to sergeant major, the highest rank available to a noncommissioned officer. Still, the life of a soldier was not well suited to one with such a consuming literary ambition, and after two years of service (he had signed up for five) Poe sought his discharge, which, he learned, could be obtained only with a letter from his stepfather. His appeals to John Allan were met with silence, until finally Allan consented to provide the letter, but only on the condition that Poe enroll as an officer candidate in the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Poe thrived at first within the strict discipline of the academy, but the ill health that would plague him for the rest of his life was beginning to emerge; as he complained in a letter to Allan: “I have no energy left, nor health, if it was possible, to put up with the fatigues of this place.” His discovery that John Allan had remarried, to a much younger woman with whom he hoped to produce a rightful heir (Allan had sired two illegiti-mate sons before his first marriage) led to an exchange of mutually accusing letters and, ultimately, Poe’s decision to withdraw from West Point—which once again required a letter from his stepfather. This time, however, Allan adamantly refused to provide one; in the long struggle between the two men, the final break was now at hand. Poe, who was growing increasingly unhappy and unwell at West Point (and beginning to seek

– 151 –

0465002573-Goodman.qxd 8/25/08 9:57 AM Page 152

the sun and the moon

comfort in brandy, which only worsened matters), decided that he had no recourse but to procure his own dismissal by refusing to attend class or perform his duties. He set himself to his task with characteristic willful-ness, earning, in a single month, an impressive sixty-six misconduct citations (the next most troublesome cadet received a mere twenty-one).

Brought before a general court-martial on charges of gross neglect of duty and failure to obey an officer, Poe pleaded guilty and was dismissed. After eight months at West Point he left with little more than the uniform on his back. He sailed down the Hudson for a brief, illness-wracked stay in New York before boarding a steamboat for Baltimore, where he found lodging with his late father’s widowed sister Maria Clemm and her young daughter: the two who would provide him a family for nearly all of the eighteen years that remained to him.

Poe had published a second book of poems just before entering West Point, and yet another while enrolled there. (He dedicated the book to his fellow cadets, who had collected the money to pay for its publication.) In the four years since his departure from the University of Virginia he had managed to produce three volumes of poetry, but none had earned for him the reputation he felt certain he deserved. He gloried in his writing even when no one else did, when his books, so lovingly composed, were derided or, even worse, ignored. He had been so often abandoned by those who once cared for him; by early adulthood he was already an intimate of wasting illness and death. Perhaps this was why he held so desperately on to his pride, for it was all he had left. Constantly he measured the distance between his present location and the golden city he imagined in his future, his own El Dorado; constantly he appraised his own position relative to those whom he considered inferior. He both needed and disdained the goodwill of others; he was supremely sensitive to slights, whether real or merely perceived, and, as Richard Adams Locke would discover, he nursed a lifelong obsession with writers he believed to be plagiarists.