The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher: A Shocking Murder And The Undoing Of A Great Victorian Detective (33 page)

Authors: Kate Summerscale

Tags: #Detectives, #Fiction, #Great Britain, #Murder - General, #Espionage, #Europe, #Murder - England - Wiltshire - History - 19th century, #Murder, #Mystery & Detective Fiction, #True Crime, #Case studies, #History: World, #Wiltshire, #Law Enforcement, #Whicher; Jonathan, #19th century, #History, #England, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Europe - Great Britain - General, #Detectives - England - London, #Literary Criticism, #London, #Biography & Autobiography, #Expeditions & Discoveries, #Biography

Nearly five years have since passed away during which time I have either been in a wild feverish state of mind only happy in doing evil, or else so very wretched that I often could have put an end to myself had means been near at the moment. I felt hatred towards everyone, and a wish to make them as wretched as myself.

At last a change came. My conscience tormented me with remorse. Miserable, wretched, suspicious, I felt as though Hell were in me. Then I resolved to confess.

I am now ready to make what restitution is in my power. A life for a life is all that I can give, as the Evil done can never be repaired.

I had no mercy, let none ask it for me, though indeed all must regard me with too much horror.

Forgiveness from those I have so deeply injured I dared not ask. I hated, so is their hatred my just retribution.

It was a beautifully composed atonement. Constance's explanation of why she killed Saville - that she wished to inflict on her bad mother the exact pain that had been inflicted on her good one - was breathtaking, at once crazy and logical, just as the killing itself had been both methodical and impassioned. There was an uncanny control to the narrative: her furious attack on a child was rendered as an abstraction; she sought an opportunity to do evil, and 'I found it.'

After the trial Dolly Williamson filed a report to Sir Richard Mayne, in a clear, curving hand. He had been told, he said, that Constance claimed she twice intended to kill her stepmother, 'but was prevented by circumstances and then the thought struck her that before she killed her she would kill the children, as that would cause her additional agony, that it was with such feelings in her heart she returned home from school in June 1860'. His informant was probably Dr Bucknill, who had discussed the murder with Constance at some length. It was not until the end of August that the alienist, in a letter to the newspapers, divulged the girl's account of how she killed Saville:

A few days before the murder she obtained possession of a razor from a green case in her father's wardrobe, and secreted it. This was the sole instrument which she used. She also secreted a candle with matches, by placing them in the corner of the closet in the garden, where the murder was committed. On the night of the murder she undressed herself and went to bed, because she expected that her sisters would visit her room. She lay awake watching until she thought that the house-hold were all asleep, and soon after midnight she left her bedroom and went downstairs and opened the drawing-room door and window shutters. She then went up into the nursery, withdrew the blanket from between the sheet and the counterpane, and placed it on the side of the cot. She then took the child from his bed and carried him downstairs through the drawing-room. She had on her nightdress, and in the drawing-room she put on her goloshes. Having the child in one arm, she raised the drawingroom window with the other hand, went round the house and into the closet, lighted the candle and placed it on the seat of the closet, the child being wrapped in the blanket and still sleeping, and while the child was in this position she inflicted the wound in the throat. She says that she thought the blood would never come, and that the child was not killed, so she thrust the razor into its left side, and put the body, with the blanket round it, into the vault. The light burnt out. The piece of flannel which she had with her was torn from an old flannel garment placed in the waste bag, and which she had taken some time before and sewn it to use in washing herself. She went back into her bedroom, examined her dress, and found only two spots of blood on it. These she washed out in the basin, and threw the water, which was but little discoloured, into the footpan in which she had washed her feet over night. She took another of her nightdresses and got into bed. In the morning her nightdress had become dry where it had been washed. She folded it up and put it into the drawer. Her three nightdresses were examined by Mr Foley, and she believes also by Mr Parsons, the medical attendant of the family. She thought the blood stains had been effectually washed out, but on holding the dress up to the light a day or two afterwards she found the stains were still visible. She secreted the dress, moving it from place to place, and she eventually burnt it in her own bedroom, and put the ashes or tinder into the kitchen grate. It was about five or six days after the child's death that she burnt the nightdress. On the Saturday morning, having cleaned the razor, she took an opportunity of replacing it unobserved in the case in the wardrobe. She abstracted her nightdress from the clothes basket when the housemaid went to fetch a glass of water. The stained garment found in the boiler-hole had no connexion whatever with the deed. As regards the motive of her crime it seems that, although she entertained at one time a great regard for the present Mrs Kent, yet if any remark was at any time made which in her opinion was disparaging to any member of the first family she treasured it up and determined to revenge it. She had no ill-will against the little boy, except as one of the children of her stepmother . . .

She told me that when the nursemaid was accused she had fully made up her mind to confess if the nurse had been convicted, and that she had also made up her mind to commit suicide if she was herself convicted. She said that she had felt herself under the influence of the devil before she committed the murder, but that she did not believe, and had not believed, that the devil had more to do with her crime than he had with any wicked action. She had not said her prayers for a year before the murder, and not afterwards till she came to reside at Brighton. She said that the circumstance which revived religious feelings in her mind was thinking about receiving sacrament when confirmed.

Bucknill finished his letter by observing that, though Constance was not in his opinion insane, even as a child she had 'a peculiar disposition' and 'great determination of character', which indicated that 'for good or evil, her future life would be remarkable'. If placed in solitary confinement, he warned, she could succumb to insanity.

Emotionally, the explanation that Constance gave Bucknill had the eerie detachment that this crime must have required. The methodology of the murder supplanted any feeling about it. At the moment of Saville's death, her focus switched from the failing body to the sputtering candle on the toilet seat: 'The light burnt out.'

Despite its air of cold precision, though, the account was strangely imprecise. Constance's story of the murder didn't add up - as the press was quick to point out. How did she fold back and smooth the bedclothes in the cot while she was holding in one arm a large, sleeping boy of nearly four? How did she, still holding the boy, bend to the ground to lift up the drawing-room window? How did she manage to then crawl under it, still without waking him, and light a candle in the water closet to which she carried him? Why did she take the facecloth to the privy, and why had no one noticed it in her room before? How was it that she had splashed only a couple of spots of blood onto her nightdress while stabbing repeatedly at the boy? How had those who searched the house after the murder missed the stains on her nightdress, and the loss of Samuel Kent's razor? And how had she managed to make those deep stabs with a razor, a feat the doctors had declared impossible? Yet some of the details, if only because they complicated the picture, were persuasive: for instance, Constance's panic when it seemed that the 'blood would never come' seemed too particular and grisly to be invented.

The Times

observed, with dismay, that the crime 'seems not to diminish in perplexity and strangeness as it is unravelled step by step. It is evident that we have not yet obtained a complete account of all the circumstances.' Even now, after a confession of murder, it seemed that there were secrets still. 'We are but little enlightened,' saisaid

the News of the World

- Constance's explanation merely added 'a new pang of horror'.

Forty years later, Freud made a gloriously confident assertion about how helplessly human beings betrayed themselves, how surely their thoughts could be read. 'He that has eyes to see and ears to hear may convince himself that no mortal can keep a secret. If his lips are silent, he chatters with his finger-tips; betrayal oozes out of him at every pore.' Like a sensation novelist or a super-detective, Freud fancied that people's secrets would flood up to the surface, in blushes and blanches, or work their way out to the world in the fingers' twitches. Perhaps somewhere in Constance's confessions and evasions the suppressed story of the crime and its motive lay in hiding, waiting to tell itself.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

SURELY OUR REAL DETECTIVE LIVETH

1865-1885

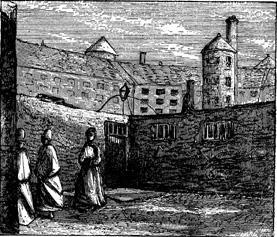

In October 1865, Constance was transferred from Salisbury to Millbank, a thousand-cell holding prison on the Thames - 'a big, dark building with towers', wrote Henry James in

The Princess Casamassima

, 'lying there and sprawling over the whole neighbourhood, with brown, bare, windowless walls, ugly, truncated pinnacles, and a character unspeakably sad and stern . . . there were walls within walls and galleries on top of galleries; even the daylight lost its colour, and you couldn't imagine what o'clock it was'. The female prisoners occupied a wing known as the Third Pentagon. A visitor to the gaol would see them 'erect themselves, suddenly and spectrally, with dowdy united bonnets, in uncanny corners and recesses of the draughty labyrinth'. The

Penny Illustrated Paper

sent a reporter to see in what conditions Constance was confined. He found Millbank 'a geometrical puzzle', 'an eccentric maze' with three miles of airless, seemingly subterranean 'twisting passages', 'dark nooks or 'doublings' in the zigzag corridors', 'double-locked doors, opening at all sorts of queer angles, and leading sometimes into blind entries, and frequently to the stone staircases which . . . seem as though they had been

cut out

of the solid brickwork'.

Constance was assigned a cell equipped with a gaslight, a washing tub, a slop pan, a shelf, tin mugs, a salt cellar, a plate, a wooden spoon, a Bible, a slate, a pencil, a hammock, bedding, a comb, a towel, a broom and a grated peephole. Like the other inmates, she wore a brown serge dress. Her breakfast was a pint of cocoa and molasses; lunch was beef, potatoes and bread; supper bread and a pint of gruel. For the first few months of her sentence she was forbidden from speaking to other inmates and from receiving visitors - the Reverend Wagner and Miss Gream applied for special permission to see her, but were turned down. Each day she cleaned her cell and went to chapel. Usually she was then set to work, perhaps making clothes, stockings or brushes for fellow prisoners. She had a bath a week, and a library book if she chose. For exercise she walked in single file, six feet behind the preceding convict, around the enclosed marshy waste ground that ringed the prison buildings. She could see Westminster Abbey to the north, smell the river to the east. Jack Whicher's home was a block away, invisible behind Millbank's high walls.

Whicher, meanwhile, took up his life again. In 1866 he married his landlady, Charlotte Piper, a widow three years his senior. If he had ever been legally married to Elizabeth Green, the mother of his lost son, she must have been dead now. The service took place on 21 August at St Margaret's, an exquisite sixteenth-century church in the grounds of Westminister Abbey, where sheep grazed on the green.

Elizabeth Gough had also married that year. At the church of St Mary Newington, Southwark, on 24 April 1866, almost a year to the day after Constance Kent's confession, she became the wife of John Cockburn, a wine merchant.

By the beginning of the next year Whicher was working as a private investigator. He didn't need the money - his pension was adequate, and the new Mrs Whicher had a private income. But now that he had been vindicated, his brain was cleared of congestion and his appetite for detection had returned.

Private inquiry agents, such as Charley Field and Ignatius Pollaky, were thought to embody the most sinister aspects of detection. Sir Cresswell Cresswell, the judge who presided over the divorce court, fulminated in 1858 against 'such a person as Field': 'of all the people in the world the people of England have the greatest objection to anything like a spy system. To have men running after them wherever they go and making notes of all their actions is what they hold in utter abhorrence. Everything of the kind is held in the greatest detestation in this country.' In Wilkie Collins'

Armadale

, published in 1866, the private detective is a 'vile creature whom the viler need of Society has fashioned for its own use. There he sat - the Confidential Spy of modern times, whose business is steadily enlarging, whose Private Inquiry Offices are steadily on the increase. There he sat - the necessary Detective . . . a man professionally ready on the merest suspicion (if the merest suspicion paid him) to get under our beds, and to look through gimlet-holes in our doors; a man who . . . would have deservedly forfeited his situation, if, under any circumstances whatever, he had been personally accessible to a sense of pity or a sense of shame.' The work was well-paid, if uncertain: in 1854 Field received fifteen shillings a day, plus expenses, to spy on a Mrs Evans, and an extra six shillings a day if he obtained the evidence of adultery that her husband required in order to divorce her.