The Sweet Smell of Psychosis (3 page)

Read The Sweet Smell of Psychosis Online

Authors: Will Self

now, standing and chatting, completely at ease, with two huge black guys dressed in string vests and dungarees. Bell was in his element, adjusting his posture to match theirs, and – Richard could just make this out above the background roar – adopting some of their tags, their Whadjas, Safes and Seens, to customise his patter, make him accessible to his listeners.

Ursula was there too. She was still pristine, even at this late hour. Richard could see no reddening of her blue eyes, or lankening of her thick, chestnut swathe of hair. Rather, the long evening of drinking seemed to have given her still more life, more embodiment. He hid behind his drunkenness as if it were a tree, and peered out at her. How could she hang around with these people? How could she witness cruel jokes like the one they'd played on the trench-coated man, without somehow becoming corrupted in her very essence? How could she?

Richard realised he was in danger of making a fool of himself He was too drunk for this. When he weaved across the crowded basement, to take his place in the terminal toilet stall to gush and drain, he banged ankles, nudged paper cups. The imprecations floated into his ears as if from a long way off

:

shouted across a vale of

tears. I'm staying up, he deliberated deliberately as he focused on the precise point at which piss exited from penis, so that she won't go home with him. Will she go home with him? Oh! Will she?!

Of course, Richard knew that she had in the past. There were hardly any of the permanent crew around Bell who hadn't. But it was merely his way of branding them with his mark, a badge of admission. Once he'd done it, he didn't do it again . . . or did he? She was so – so

fucking desirable.

Perfect figure: large, pointed breasts, requiring no girding or uplift; waist cinched for holding; swivel hips and long, lolloping legs; and that face! The eyes permanently, violet-violently astonished; the brows straight slashes of brown; the whole rounded and yet sharp, with skin of an absolute pink flawlessness stretched over it. Ursula had told Richard – apropos of nothing – that she never wore makeup; that her toilet consisted only of a little moisturiser, and Jicki, the subtle, irrepressibly erotic fragrance created by Guerlain for the Empress Eugénie.

A little moisturiser! Richard wanted to be the little moisturiser. Wanted to be dabbed by a cotton-wool pad against those cheeks, that neck, those breasts. Oh Jesus! She wouldn't cross the road to piss on him, he

was certain of that. But he couldn't leave her here. He couldn't . . .

‘. . . Still hanging in, are we, young Richard?’ said Todd Reiser, looming over him. Reiser could do this because Richard was slumped down on the stool. The director was a nice example of praxis: he was short, and he also shot shorts. He also wore irritating jeans, which should have been but weren't creased. He affected shirts of heavy texture as well, and Richard couldn't forbear from imagining still grimmer top garments in the recesses of the Reiser wardrobe – zip-up cardigans, and sleeveless Fair Isle sweaters. ‘You know, I don't think you stand much of a chance in that direction . . .’ Reiser smirked – so it seemed to Richard – his entire body towards the lovely Ms Bentley.

A small compartment full of bile opened up in the back of Richard's throat. ‘W'f, w'reurgh,’ he expostulated, then found himself up on his hind legs, tottering like a foal soused with Campari, and also – equally involuntarily – muttering ‘G'night’ in Bell's, Ursula's and Reiser's general direction. Then he was in Old Compton Street haggling prices with the tribally scarred, clipboard-bearing cab controller, outside the kiosk by the Pollo Bar.

Soon afterwards the cab was heading north, up Tottenham Court Road. Richard slopped around in the back seat, mostly anaesthetised, yet at one and the same time fully alert to the shock of tyre over pothole.

At the junction with the Euston Road a huge hoarding was positioned so as to obscure a building site abutting the Euston Tower. Richard bleared at the thing, seeing dawn flush above its top edge – and then took it in more fully. It was one of those three-in-one hoardings, a rack of rotating triangular bars; and as the cab idled by the lights, a woman's pudenda encased in a flawless, silken second skin started to riffle like a pack of cards being spread for the cut, and gave way to those familiar features, the red lips, the broad-bridged nose. Bell's warm, black eyes looked out at Richard; Bell's big digit tapped Bell's high, white forehead. The advert's slogan was the last thing that the hoarding made legible, flipped over into comprehension: ‘All Through the Night on MW 1053/1089 kHz. Get Hold of That Clapper – and Ring Me, Bell.’

The traffic lights clicked, the parted legs of the green iconic man married, the cabbie engaged drive, the car lurched forward, Richard's head fell back against the seat. Where were those red lips now? Perhaps nuzzling

the silken skin that encased Ursula? Richard groaned throatily; the cabbie scrunged round in the mock-leather confines of his car coat. ‘What yer doin'?’ he demanded, sensing with professional acumen the vomit and bile that were welling in Richard's throat.

‘No – gr'nff – no really, ‘s all right.’

They drove on. Never had Hornsey seemed so much of a haven to Richard.

The following morning Richard was sitting in the editorial meeting at

Rendezvous,

the loathsome and affected listings magazine he worked for, when one of the subs came in with a Post-it note fluttering on her fingertip. She walked round to where Richard was sitting – next to his superior, the glove fetishist – and transferred the adhesive notelet from her finger to his. Richard squinted down at the scrap of information. It read: ‘Ursula Bentley rang. Please call her on 602 3368.

Urgent!‘

Richard hadn't been thinking about Chico Fran-quini's new film

Grave Robber,

nor had he been giving much attention to the forthcoming Shell Oil Festival of Indigenous Music; the Kandinsky show at the Bankside did not impinge, and neither did Company Corneille's

staging at Sadler's Wells of the original Diaghilev

Rite of Spring.

On the muddy, polluted foreshore of Richard's consciousness, the cultural waves slapped limply; towards the horizon a ruptured tanker wallowed in the curdling sea. Richard had grasped the magnitude of the disaster at dawn, in bed in Hornsey, when he saw the thick slick of wine, beer and vodka gushing from the tanker's hull, and the dark pall of dope smoke overhead.

It was going to be a day of getting through things – endeavouring to persevere. This was not a day when Richard was going to take a fearless moral inventory and remedy his ethical deficiencies. He could just about see his way to feeling the shape of the ulcers his teeth had worried into being on the insides of his cheeks; he would do his best to disregard the phantom fat fingers that encapsulated his own; towards lunch he might counsel the atrocity exhibition of a bowel movement.

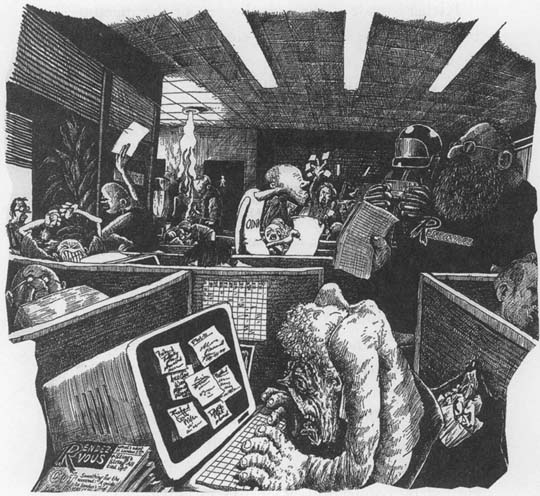

The

Rendezvous

office was hell on hangovers. Under the unphotogenic glare of strip lighting, a more than averagely nasty open plan – floor and ceiling tiling clashing and gnashing together, mashing the intervening space – was networked with thorax-high, freestanding bafflers of some composite material, covered in fabric

with a rough, oatmealy nap. The journalists, subs, production people, secretaries, designers and gofers who tenanted this stunted maze moved about the place at some speed, fetching and carrying bits of paper; or else bobbed up above the partitions, to shout to some colleague that copy was coming – along the cable tracking.

Gathering by the water-cooler, on the landing outside the toilets, or on the fire stairs, the staff of

Rendezvous

smoked Silk Cut, and took tiny options on the future preoccupations of the mass of their fellow Londoners. They earnestly debated the opening of themed restaurants, and the demise of experimental opera productions, as if they were matters of millennial import that would define an era. Even on a good day it made Richard feel nauseous.

The apex of this pyramid of ephemera, ministered to by a pretentious priesthood, was the morning editorial meeting. As a deputy section editor, Richard attended this two days a week. These were the meetings at which things actually got done – when it was the section heads alone, they merely intrigued. But after all, Richard thought, what did his work consist of? Reducing some forthcoming event still further than it

reduced itself? Producing a kind of stock of the culture? He would write a hundred and fifty words, on a novel, a play, an album, append to it a photograph the size of a postage stamp, and often – in his unhumble opinion – he would have dealt with the subject matter, the themes, better than the original.

This morning's meeting was more than averagely awful. The Editor, whose patter was compounded in equal parts of managementspeak and manipulation, was making it his business to humiliate the editor of the performance section, an unstable man with aburgeoning heroin habit. There would be tears before elevenses, Richard was thinking grimly, when the note arrived.

Her note. It smashed through the partitions – her note; and it crashed through the glass walls of the Editor's office (he'd had them installed after seeing

All the President's Men

). It ushered in a coconut-scented breeze, the sound of a Hawaiian guitar. The thick slick of alcohol began to be cleaned up with the detergent of desire. The dark pall of dope smoke wavered and dispersed. His eyes still clamped on the Post-it note, Richard saw the future opening up before him like some virgin land. It was a future in which Ursula Bentley called him at the office. It was nirvana.

Richard made it through the rest of the meeting by grinding the shaft of his erect penis against the underside edge of the conference table until a sharp pain ran down his inner thigh. Once or twice he thought that this extraordinary practice might actually cause him to ejaculate, but he had to do it, had to prevent himself from being carried away on a cloud of mucal imaginings. Richard didn't even rise when the glove fetishist – in a lull – flicked his golden calf of a Post-it note with a fake nail and insinuated, ‘Well, Richard, Ursula Bentley eh? Pretty thing, isn't she – although, to coin a phrase, she's had

her

bell rung a fair few times, hmm?’

As soon as the meeting ended, Richard sprinted through the maze of partitioning like an experimental rat hurrying to get an on-demand hit of cocaine. He crouched down in the cul-de-sac that served him as an office space, and dialled the number on the note. It was a Kensington exchange. As the mist of static was cleared by connection, Richard's imagination called up a vision of Ursula in her Kensington flat, with its high, high ceilings, its quarter-acre of Persian rug, its cabinets full of rare

objets d'art.

There she was, Ursula, a Maughamesque figure, reclining on a deco divan in a

bay window. Her gown was long, falling in columns and scallops of ivory material. There was gold at her breast, worked into her girdle, and at hem and sleeve as well. Her telephone receiver was sculpted in the form of an epicene young man, an Adonis – like Ursula herself, formed of ivory and gold.

‘Yeah?’ Ursula's voice rasped.

‘Is – is that Ursula? Ursula B-Bentley?’ Richard didn't so much reply, as warble.

‘Yeah.’

‘It's Richard, Richard Hermes.’

‘Oh, yeah, young Richard. You scarpered a bit quick last night. What happened?’ Her voice was harsh – but not to his ear.

‘Um, well, work in the morning y'know – ‘ Fool! He didn't know that she knew anything of the sort. Apart from her column ('Peccadillo’, which some wags referred to as ‘Pick-a-Dildo'), Richard had no idea of what Ursula did. But judging by the way in which she waved aside everything that pertained to money – like her share of the bill – the world of work was something she orbited, rather than inhabited.

‘At

Rendezvous,

with what's her name, that glove woman.’

‘Sorry?’ He was sorry all right, sorry that anything should connect these two. He felt as if (and this was an overarching absurdity) he had betrayed Ursula already, committed proleptic adultery.

‘You know, Richard, your boss, Fabia, the glove woman. Don't tell me she hasn't tried it on with you. She got me in the coat room at some party once. I was a bit pissed, so we sort of started snogging, whatever. Then she pulled some ski gloves out of her pocket, the thick, quilted kind. Tried to get me to give her a right good frigging with them. Since then I've heard all sorts about her – but always with the glove angle. What was it with you? Leather driving numbers with holes? Mittens?’