The Sword And The Olive (30 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

Next, the officer commanding the southern front used the absence of the chief of staff in order to send armored forces into battle well ahead of time, a move so disruptive of everything the General Staff had planned that Dayan, who went to see a sick Ben Gurion late on October 30, did not even dare inform him that it had happened. Advancing toward Al-Agheila, units from Ben Ari’s 7th Armored Brigade ran into others of 37th Brigade, opened fire on them, and knocked out several tanks before recognizing that their opponents were not Egyptians but other Israelis. True to Dayan’s “system” of supply, the advance of Eytan’s paratroopers from Mitla Pass to A-Tur was made without any logistic preparations at all so that they all but starved on the way. Bypassing the pass by way of En Sudar to the south, incidentally this move served as an additional proof that the battle for Mitla Pass had been totally unnecessary.

Last but not least, the IAF—apparently intent on filling

its

quota of blunders—opened fire on HMS

Crane

, which was patrolling Sharm al-Sheikh, causing a fire (according to the pilots’ reports) but inflicting only superficial damage (according to the British captain).

82

What’s more, on two different occasions IAF aircraft strafed their own forces, which in typical IDF fashion had taken over captured Egyptian vehicles without bothering to repaint them or even provide them with fresh insignia visible from the air. In this too, Dayan, who seemed to personify the IDF, set the example. Arriving at A-Tur on November 6, he found that somebody had blundered and that no arrangements to take him to Sharm al-Sheikh had been made. Accordingly he and his party commandeered an Egyptian car. Next they headed south and almost got themselves killed when they ran into Eytan’s paratroopers, already on their way back.

83

its

quota of blunders—opened fire on HMS

Crane

, which was patrolling Sharm al-Sheikh, causing a fire (according to the pilots’ reports) but inflicting only superficial damage (according to the British captain).

82

What’s more, on two different occasions IAF aircraft strafed their own forces, which in typical IDF fashion had taken over captured Egyptian vehicles without bothering to repaint them or even provide them with fresh insignia visible from the air. In this too, Dayan, who seemed to personify the IDF, set the example. Arriving at A-Tur on November 6, he found that somebody had blundered and that no arrangements to take him to Sharm al-Sheikh had been made. Accordingly he and his party commandeered an Egyptian car. Next they headed south and almost got themselves killed when they ran into Eytan’s paratroopers, already on their way back.

83

Had even one of these “misfortunes” taken place after 1985 or so, the resulting outcry would have been deafening. At the time, however, they were swallowed up by the combination of

en brera

on the one hand and censorship on the other. The inadequate performance of 38th

Ugda

and the resulting changes in command were known only to a select few, given that the IDF was not and still is not in the habit of disclosing the names of its division and brigade commanders. Inside the IDF, Sharon’s unauthorized action at Mitla Pass was sharply criticized by his own men, who accused him of reputation-building at their expense.

84

Talking to Ben Gurion, Dayan was almost equally critical, but in his published account of the campaign he was content to write, “I regard the problem as grave when a unit fails to fulfill its battle task, not when it goes beyond the bounds of duty.” Instead of the public attacking the IDF for taking unnecessary casualties, it took Dayan to task for disclosing the matter in “disregard [of] the feelings of widows, orphans and bereaved parents whose loved ones fought and died in the Mitla.”

85

To blunt the impression, the story of one of Gur’s paratroopers, Yehuda Ken-Dror, who sacrificed himself by deliberately drawing Egyptian fire, was given wide circulation—thus confirming the old adage that behind every hero there is a blunder.

en brera

on the one hand and censorship on the other. The inadequate performance of 38th

Ugda

and the resulting changes in command were known only to a select few, given that the IDF was not and still is not in the habit of disclosing the names of its division and brigade commanders. Inside the IDF, Sharon’s unauthorized action at Mitla Pass was sharply criticized by his own men, who accused him of reputation-building at their expense.

84

Talking to Ben Gurion, Dayan was almost equally critical, but in his published account of the campaign he was content to write, “I regard the problem as grave when a unit fails to fulfill its battle task, not when it goes beyond the bounds of duty.” Instead of the public attacking the IDF for taking unnecessary casualties, it took Dayan to task for disclosing the matter in “disregard [of] the feelings of widows, orphans and bereaved parents whose loved ones fought and died in the Mitla.”

85

To blunt the impression, the story of one of Gur’s paratroopers, Yehuda Ken-Dror, who sacrificed himself by deliberately drawing Egyptian fire, was given wide circulation—thus confirming the old adage that behind every hero there is a blunder.

The extent of Western involvement in the war, including the presence of three French fighter squadrons and one of transport, was also downplayed. With very few exceptions the Israeli public felt delirious with victory—telling itself that this five-day, two-division campaign had been “one of the most brilliant of all time” (Shimon Peres)

86

and “unequaled since the days when Hannibal crossed the snowy Alps and Genghis Khan, the mountains of Asia.”

87

From cabinet ministers down, hordes of visitors descended on the Sinai in a holiday mood, seeking remains of the Exodus and using a passage from the sixth-century Byzantine author Procopius to convince themselves that it was somehow Israeli territory. Ben Gurion himself at one point ranted about his plans for retaining Sharm al-Sheikh and founding the “Third Kingdom of Israel”; whether this was seriously meant or merely represented a starting point for the inevitable negotiations remains immaterial.

88

The inevitable popular songs appeared as if out of nowhere, were broadcast on the radio, and sold on records. “This is neither legend nor dream my friends,” the best known among them thundered, “this is the people of Israel face to face with Mount Sinai.” Having defeated its enemy, the IDF, riding sky-high, felt it could face its future with confidence.

86

and “unequaled since the days when Hannibal crossed the snowy Alps and Genghis Khan, the mountains of Asia.”

87

From cabinet ministers down, hordes of visitors descended on the Sinai in a holiday mood, seeking remains of the Exodus and using a passage from the sixth-century Byzantine author Procopius to convince themselves that it was somehow Israeli territory. Ben Gurion himself at one point ranted about his plans for retaining Sharm al-Sheikh and founding the “Third Kingdom of Israel”; whether this was seriously meant or merely represented a starting point for the inevitable negotiations remains immaterial.

88

The inevitable popular songs appeared as if out of nowhere, were broadcast on the radio, and sold on records. “This is neither legend nor dream my friends,” the best known among them thundered, “this is the people of Israel face to face with Mount Sinai.” Having defeated its enemy, the IDF, riding sky-high, felt it could face its future with confidence.

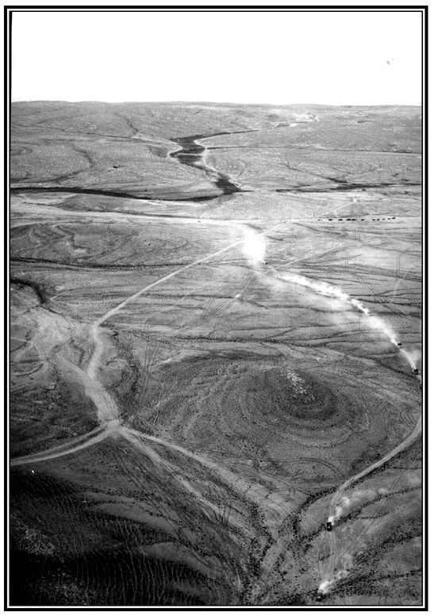

Building a Modern Army: motorized column on maneuver, 1965.

CHAPTER 10

BUILDING A MODERN ARMY

A

LTOUGH MILITARILY a success, the Suez campaign of 1956 did not fundamentally change the balance of power between Israel and its neighbors.

1

If anything the opposite was the case; the war was one more demonstration of Israel’s inability to translate military victory into political achievement. Not only was there no question of forcing the other side to change their policy and make peace; Israel was unable to retain any of its gains. Coming under heavy international pressure, it was compelled to withdraw early next year.

LTOUGH MILITARILY a success, the Suez campaign of 1956 did not fundamentally change the balance of power between Israel and its neighbors.

1

If anything the opposite was the case; the war was one more demonstration of Israel’s inability to translate military victory into political achievement. Not only was there no question of forcing the other side to change their policy and make peace; Israel was unable to retain any of its gains. Coming under heavy international pressure, it was compelled to withdraw early next year.

To be sure, the campaign was not altogether without benefits. The power of the IDF to defeat its enemies had been demonstrated. The objective of opening the Straits of Tyran to Israeli traffic, both naval and airborne, was achieved. The Sinai Peninsula was demilitarized, and a small UN peacekeeping force was inserted between Israel and its most powerful enemy. Moreover, Israel was allowed to remilitarize Nitsana, a small but strategically important border area opposite Abu Ageila. Once back to its own borders, however, the state reverted to being “a small island in an Arab sea.” It also retained all the old vulnerabilities, including a long and wide-open border, an exceedingly narrow strategic “waist,” and of course the overall disparity between it and its much larger enemies, who surrounded it on all sides except the western.

Against this geopolitical background, easily understandable to anybody who so much as bothered to glance at the map, the feeling of

en brera

not only survived but grew even stronger. As before, Israeli public opinion continued to see the IDF as the one great organization standing between it and death. Even more than before, it was prepared to do its utmost to ensure the army’s success by providing the necessary resources in terms of materiel and the very best manpower at its disposal (that originating in the

kibbutsim

, which, rightly or not, was considered by themselves and others to constitute the crème de la crème.

2

The rejection of diaspora “cowardice” intensified; year in and year out the most important question tens of thousands of schoolchildren were asked when confronted with the Holocaust was not how it could have happened but why “the Jews” had gone

ka-tson la-tevach

(like sheep to the slaughter). For those who joined the IDF as eighteen-year-old conscripts there was now a new generation of former Sinai heroes to emulate. Israeli-born and for the most part without religious sentiments, they were, in the words of the well-known writer Amos Oz, a race of “circumcised Cossacks.”

3

en brera

not only survived but grew even stronger. As before, Israeli public opinion continued to see the IDF as the one great organization standing between it and death. Even more than before, it was prepared to do its utmost to ensure the army’s success by providing the necessary resources in terms of materiel and the very best manpower at its disposal (that originating in the

kibbutsim

, which, rightly or not, was considered by themselves and others to constitute the crème de la crème.

2

The rejection of diaspora “cowardice” intensified; year in and year out the most important question tens of thousands of schoolchildren were asked when confronted with the Holocaust was not how it could have happened but why “the Jews” had gone

ka-tson la-tevach

(like sheep to the slaughter). For those who joined the IDF as eighteen-year-old conscripts there was now a new generation of former Sinai heroes to emulate. Israeli-born and for the most part without religious sentiments, they were, in the words of the well-known writer Amos Oz, a race of “circumcised Cossacks.”

3

Under these circumstances, the highest praise one could bestow on anything was to say that it was

kmo mivtsa tsvai

(like a military operation). Far from doffing their uniforms when on leave, Israeli youngsters liked to wear them even on social occasions, when anybody sporting the insignia of an officer’s rank considered himself at least a demigod. As Ezer Weizman wrote, combat aircraft were admired not just for their performance but for their supposed beauty,

4

an attitude that sometimes led to excess, as when air force mechanics set out to decorate planes at a financial cost that no military organization, let alone the IAF, could tolerate.

5

In the late 1960s the El Al Airlines office on London’s Regent Street was even decorated with triangles suggestive of diving Mirage fighters. However, perhaps the best place to observe the difference in outlook between Israel and the rest of the world was the Four Days March. Held in the Netherlands each year, the march was a popular sporting event. To thousands of participants from various countries it was an innocuous occasion in which to walk and socialize. Not so the platoon of IDF men and women who participated each year, armed with Uzi submachine guns. They would storm the twenty-five-mile course as if their lives depended on it, always insisting on arriving first and, upon crossing the finish line, breaking into the mandatory

hora

dance to show what a lark it had all been.

kmo mivtsa tsvai

(like a military operation). Far from doffing their uniforms when on leave, Israeli youngsters liked to wear them even on social occasions, when anybody sporting the insignia of an officer’s rank considered himself at least a demigod. As Ezer Weizman wrote, combat aircraft were admired not just for their performance but for their supposed beauty,

4

an attitude that sometimes led to excess, as when air force mechanics set out to decorate planes at a financial cost that no military organization, let alone the IAF, could tolerate.

5

In the late 1960s the El Al Airlines office on London’s Regent Street was even decorated with triangles suggestive of diving Mirage fighters. However, perhaps the best place to observe the difference in outlook between Israel and the rest of the world was the Four Days March. Held in the Netherlands each year, the march was a popular sporting event. To thousands of participants from various countries it was an innocuous occasion in which to walk and socialize. Not so the platoon of IDF men and women who participated each year, armed with Uzi submachine guns. They would storm the twenty-five-mile course as if their lives depended on it, always insisting on arriving first and, upon crossing the finish line, breaking into the mandatory

hora

dance to show what a lark it had all been.

The extremely high prestige of the IDF also made it possible to use the armed forces for achieving a variety of social goals. Germany, France, Italy, and Japan (from about 1870 on) and Russia (after the 1917 revolution) regarded their armies as “the school of the nation.” Accordingly they entrusted them with all kinds of missions, from acquainting workers with the blessings of rural life by means of milking competitions (the German army before 1914) through technical training to political indoctrination in the virtues of republicanism or unity or Shinto or whatever. The same was true of the IDF, except that it went farther than most. Already in 1949, Ben Gurion had written that “the army must serve as an educational and pioneering center for Israeli youth—for both those born here and newcomers. It is the duty of the army to educate a pioneer generation, healthy in body and spirit, courageous and loyal, which will unite the broken tribes and diasporas to prepare itself to fulfill the historical tasks of the State of Israel through self-realization.”

6

As late as 1991 a retired brigadier general argued that “the army is probably the last national framework within which it is possible to have an impact on Israeli youth and to influence the values that will accompany them throughout life.”

7

In between the two dates similar ideas concerning the educational role of the military have been repeated a thousand times in every possible forum.

6

As late as 1991 a retired brigadier general argued that “the army is probably the last national framework within which it is possible to have an impact on Israeli youth and to influence the values that will accompany them throughout life.”

7

In between the two dates similar ideas concerning the educational role of the military have been repeated a thousand times in every possible forum.

Like most modern armies, the IDF carries out its internal and external propaganda activities by various means, including countless lectures, “cultural events,” shows, open days, a range of publications, and a radio station popular among young people in particular.

8

However, it has also developed a series of unique instruments that have no parallel in other countries and that need to be briefly discussed here. The first consisted of special courses for conscripts—most of them from Oriental countries—who did not know Hebrew or had not completed elementary education.

9

Somewhat similar courses were provided to civilians, often females and the mothers and sisters of those very soldiers, who had immigrated from Oriental countries and who, in addition to being even shorter on formal education than their menfolk, supposedly did not yet understand the meaning of Israeliness. The instructors were young female soldiers who after receiving a brief training course fulfilled their period of service in this way. In teaching civilians they were often sent to live in villages and townships.

8

However, it has also developed a series of unique instruments that have no parallel in other countries and that need to be briefly discussed here. The first consisted of special courses for conscripts—most of them from Oriental countries—who did not know Hebrew or had not completed elementary education.

9

Somewhat similar courses were provided to civilians, often females and the mothers and sisters of those very soldiers, who had immigrated from Oriental countries and who, in addition to being even shorter on formal education than their menfolk, supposedly did not yet understand the meaning of Israeliness. The instructors were young female soldiers who after receiving a brief training course fulfilled their period of service in this way. In teaching civilians they were often sent to live in villages and townships.

The second program run by the IDF in its nation-building role is GADNA (Gdudei Noar, or Youth Battalions).

10

Originating in the prestate days when high-school students were often used for auxiliary tasks such as running messages, in principle GADNA was supposed to inculcate all Israeli youth with love of country, self-confidence, and a modicum of premilitary training that would make it easier to adjust to army life when the time came. Subjects taught included drill, fieldcraft, topography, and the firing of subcaliber weapons. From time to time hikes were organized, during which selected members proudly carried rifles and even light machine guns. Some youths spent a full month of their summer vacations taking a sort of basic training course, after which they would be formally appointed GADNA corporal. All these activities were fully incorporated into the school system, which set aside one hour each week for the purpose and even graded students on GADNA activities. Attempts were also made to reach youths who had dropped out of the formal education system, although on the whole they were less successful. The instructors and needed equipment were provided by the IDF.

10

Originating in the prestate days when high-school students were often used for auxiliary tasks such as running messages, in principle GADNA was supposed to inculcate all Israeli youth with love of country, self-confidence, and a modicum of premilitary training that would make it easier to adjust to army life when the time came. Subjects taught included drill, fieldcraft, topography, and the firing of subcaliber weapons. From time to time hikes were organized, during which selected members proudly carried rifles and even light machine guns. Some youths spent a full month of their summer vacations taking a sort of basic training course, after which they would be formally appointed GADNA corporal. All these activities were fully incorporated into the school system, which set aside one hour each week for the purpose and even graded students on GADNA activities. Attempts were also made to reach youths who had dropped out of the formal education system, although on the whole they were less successful. The instructors and needed equipment were provided by the IDF.

The IDF’s third major nation-building instrument was the previously mentioned NACHAL. The idea that settling the land also constituted a form of defense activity had deep roots in prestate days, when it was a question of “delivering” the land from its desolation and, as often as not, its Arab inhabitants. Between 1941 and 1948 it was embodied in PALMACH; indeed more so than the IDF would have liked, because many PALMACH personnel left the army after 1949 and returned to their

kibbutsim

. When Ben Gurion first proposed the Chok Sherut Bitachon (National Service Law) of 1949 to parliament he had in mind a system whereby every IDF soldier would spend a year doing agricultural work after receiving basic training.

11

This did not go over well with his centrist coalition partners, however, and in the end a compromise was struck. In theory, to this day every IDF conscript is liable for a year’s agricultural work. In practice, NACHAL was limited to volunteers of both sexes (males were grouped in an elite infantry brigade). The number of volunteers, most of them

kibbuts

members or graduates of various youth movements, has proved sufficient to involve the IDF in a sustained colonization effort. Over the years it has produced dozens of settlements both inside the green line (the pre-1976 armistice line) and, since 1967, the Occupied Territories.

kibbutsim

. When Ben Gurion first proposed the Chok Sherut Bitachon (National Service Law) of 1949 to parliament he had in mind a system whereby every IDF soldier would spend a year doing agricultural work after receiving basic training.

11

This did not go over well with his centrist coalition partners, however, and in the end a compromise was struck. In theory, to this day every IDF conscript is liable for a year’s agricultural work. In practice, NACHAL was limited to volunteers of both sexes (males were grouped in an elite infantry brigade). The number of volunteers, most of them

kibbuts

members or graduates of various youth movements, has proved sufficient to involve the IDF in a sustained colonization effort. Over the years it has produced dozens of settlements both inside the green line (the pre-1976 armistice line) and, since 1967, the Occupied Territories.

Other books

Highlander Untamed by Monica McCarty

Samurai's Wife by Laura Joh Rowland

The Art of Ruining a Rake by Emma Locke

Luck on the Line by Zoraida Córdova

Me & Emma by Elizabeth Flock

Carol's Mate by Zena Wynn

Samurai by Jason Hightman

The Road Sharks by Clint Hollingsworth

Charades by Janette Turner Hospital

The Lynx Who Purred for a Sidhe Prince by Hyacinth, Scarlet