The Tenth Saint (26 page)

“Don’t stand there. Give me a hand,” one of the crew shouted as he tossed him a length of rope.

Gabriel resisted the thought that as a paying passenger, he shouldn’t have to work on board this ship. The concept was unknown to these people. He said nothing and did what had to be done.

Adulis was remarkably active in the dark of night. Traders negotiated prices for their goods with the local merchants, their voices loud and their tone unassailable. Some men traded gold and ivory; others peddled spices; others sold slaves. The latter practice was particularly appalling to Gabriel, not because he was ignorant of it but because it had never unfolded before his eyes. Strong young lads and beautiful women were displayed on wooden platforms, their ankles bound with iron shackles, while rich Arabians evaluated them for potential servitude. The slaves were serene of countenance and regarded their would-be lords with submissiveness and respect, their fate with acceptance.

After a lifetime of human rights conditioning, Gabriel could not view such a spectacle with tolerance. But as a stranger in this land, he could not make trouble. The notion of freedom and liberation had not hit these shores.

Against his own convictions, he turned away and kept walking on the road to the mountains whose silhouettes he could barely make out against the starlit sky.

A couple of blocks away, scrawny black men kneeled at the steps of a basalt-hewn church, chanting. He approached the church and inhaled the scent of burning frankincense emanating from the stone halls. The melodic chants of the liturgy, meant to fill the parishioners with the presence of God, floated in the air like a gossamer veil. He recognized a few words of Greek but could tell from the pronunciation it was a bastardized version of the language. He peered inside the structure and saw a priest cloaked in clean white robes, golden embroidered sashes cascading down the front of his dress, as he presided over a blessing ceremony. Behind him were icons of black faces draped with colorful robes and encircled with golden halos, each a protagonist in a biblical scene. On a wooden table sat a filigreed silver cross carved as elaborately as lace. Slim brown beeswax candles burned on a bed of sand. He was surprised to see a Christian ceremony in what he considered heathen lands.

He recalled a few words of the language from that summer he’d spent in the Greek islands, the same summer he’d met Calcedony, and tried his luck on one of the bystanders. Pointing toward the mountains, he asked, “What is there?”

The dark figure nodded but answered in a different language. Gabriel could not understand a word of it, except for a single name the man kept repeating: “Ak-sum.” That needed no further explanation. Gabriel knew something of the story of the Aksumite kingdom, the great empire connecting Africa and Arabia as a hub for trading between the two continents.

Suddenly the church scene made sense. This was one of the first places beyond the Holy Land to embrace Christianity. He was sketchy on the details but remembered that the religion was brought to those lands by missionary monks and embraced by an Aksumite king who later imposed it on the people. It was sometime in the fourth century, though of the exact dates he was not certain. Still, he knew he was in the ballpark, and that alone was a huge revelation.

For years he had not known where in history’s timeline he existed. Knowing where he was and when gave him a point of reference and, as such, an advantage. He waved his thanks to the Adulian and walked toward the mountain.

Gabriel was unsure what awaited him in Aksum, but he had high hopes. He imagined palaces and temples and an air of plenty. People would be civilized there, perhaps even learned. There would be traders and scholars and court ladies draped with beautifully embroidered cloths and gold ornaments. Perhaps the Aksumites would accept him, even listen to what he had to say and preserve it for future generations. His cynical mind, blackened and scarred from loss and despair, slowed him but was not enough to stop him.

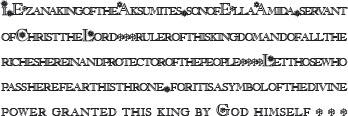

When he came to a massive granite obelisk in the road, he knew he was approaching the city. Inscribed in ancient Greek, the language of the Aksumite kings, it must have been a stele of some sort or a monument to an unusually hard-won battle. His knowledge of ancient Greek was limited, but he could make out some words.

“King Ezana,” Gabriel murmured. “Let’s hope he is more tolerant than he is humble.”

By nightfall the next day, he reached the ridge above the city and looked upon the ghostly labyrinth of stone structures beneath. He knew this was the place of his dreams, the place Hairan had told him he must come to at all costs. On a hill away from the center was perched an imposing fortress, its granite ramparts illuminated by torchlight. The palace. King Ezana’s lair.

Gabriel started to descend into the city. When he heard the howl of wolves, the cacophony of calls surrounding him, he thought better of it. His chances of avoiding an attack in full moonlight were slim. He ducked into a hollow in the granite and was pleased to discover it was the mouth of a cave that cut deep into the mountainside.

A shaft of moonlight faintly illuminated his passage as he crawled inside. The ground was slippery, the air acrid, and he wondered how long before the bats would return from their nocturnal adventures to claim their home. Determining he had until daybreak, he chose a smooth lean-to and passed what was left of the night.

Eighteen

T

he bedroom of her childhood was just as Sarah remembered. The heavy curtains of Wedgwood blue and yellow chintz were tied back with huge navy silk tassels, framing a picture window toward the west lawn. The morning light shimmered across the Tuscan-style reflecting pool her father had installed as a gift to her mother after a particularly memorable trip to Italy. Her bed was draped in blue and yellow-striped fabric and crowned with a canopy of the same chintz of the curtains, lined with yellow silk gathered to a rosette in the center. The linen sheets, pressed to a perfect knife-edge by the laundry staff, brought back memories of sleeping late on the weekends in the comfort of her crisp, warm cocoon.

She hadn’t slept in that bed since her visits home from university. After her mother’s death, she had found it too painful to be in Coddington Manor for any length of time. It was full of memories: gardening with Mum on spring mornings, taking long strolls together in the surrounding hillside, watching her cook the Sunday roast as she always insisted on doing despite the cook’s protests. For Sarah, the place no longer had the same meaning. Without her mother’s warmth, it was a shell of privilege and nothing more.

Sir Richard walked into the room without knocking and approached Sarah’s bed. He looked his usual dapper self. Standing at six feet two, he had a slim frame that gave him an aristocratic elegance. His thin, golden-brown hair was parted in the middle and combed back in orderly rows. He wore his tennis whites and his fair face was flushed, indicating he’d just come off the court.

“Well, good morning, young lady.” His voice was clear and loud with the standard measure of pomp. “At last you are awake. You’ve been sleeping the past two days, you know. Gave us quite a scare.”

“I feel awful, Daddy.” Her words came out coarse and crumpled, as if they had been locked away too long in a trunk of disuse. “What’s happened?”

“What’s happened is you were on death’s door, my girl. You had—well, have, really—a frightful case of dysentery, dehydration, and a nasty lung infection. You’re not out of the woods yet.” He nodded toward an IV drip she hadn’t noticed. “Very powerful antibiotics, those. You’ll be on the mend in no time.”

Sarah turned her aching head slowly in the direction of the west-facing window. How different the Wiltshire countryside was to the harsh Ethiopian landscape that had become her world. She regretted how wrong things had gone.

“Now suppose you tell me how you got into that sticky situation in the first place.”

She felt the weight of his judgment, but it seemed insignificant after all she’d been through. There was no reason to hold anything back. She told him the whole truth, starting with her defection to Yemrehana Krestos and ending with their kidnapping and near execution. Sir Richard listened intently, quietly taking it all in but obviously making mental notes for the interrogation Sarah fully expected. By the time she finished her narration, she was winded.

“Something is not clear. Why would a brilliant archaeologist who’s been the star of such a fine institution as Cambridge defy the wishes of her superiors and go off on a wild-goose chase? Please do explain this to me, Sarah, because for the life of me I don’t understand.”

“I wouldn’t expect you to. You never have.”

“Well, considering I have just imposed on Her Majesty’s government to intervene in Anglo-Ethiopian relations and have enlisted the services of Scotland Yard agents in order to rescue you from a situation you could have and should have avoided, I would say you owe me at least this.”

“You were an explorer once,” she said, trying to explain in terms he could understand. “Surely you didn’t do it for academic glory or because Her Majesty’s government asked you to. You understood there was something finer, something beyond weekend hunts and cocktail chatter, and you went looking for it, fully expecting that no knowledge worth having would come easy. Finding the truth is a journey, a risky one. You taught me that, if only by your actions.”

Before he had a chance to reply, his cell phone rang. He picked up, murmured something into the receiver, and quickly hung up. “Urgent business, I’m afraid. I must be off. But do know this conversation is not over.”

“I hope not. I’ve got much more to say to you.”

“I’ve asked Daniel Madigan to come for dinner. He will be driving in from London this afternoon. He has been asking after you every day. If you ask me, the chap seems quite taken by you. You should feel honored.”

The thought of Daniel’s visit pleased Sarah. She was eager to thank him. Encouraged by the powerful meds, she let herself fall into sleep’s embrace.

When Sarah opened her eyes, Daniel was sitting on the edge of her bed. He looked so different now that he had shaven, combed his long locks into a ponytail, and put on respectable clothes. More like a civilized American scholar than the dusty field scientist she had grown accustomed to.

She abruptly sat up. Almost ripping the IV out, she lunged into his arms.

They embraced for a long time.

“You sure look better than you did a week ago,” he said.

“Oh, stop it. I look a fright.” Suddenly self-conscious, she tried to straighten her wayward curls. “How are you?”

“Happy to be alive. We owe your dad a big debt of gratitude. This was no small rescue operation, apparently.”

“I imagine you boys discussed it over gin-tonics already.”

He winked. “That’s what we boys do. Long story short, they traced the call you placed to Stan Simon and learned the mobile phone was registered to a Mr. Amanuel Abombo, apparently a deliveryman in Addis. They researched Abombo and found that he once had very shady connections to the Chinese mob. Old boy helped them move some weapons illegally, it seems. The agents informed him he was under arrest for his crimes and his sentence would be far more lenient if he cooperated. He sang like a lark.”

“What was his connection to Matakala?”

“There was no direct connection to Matakala. Abombo knew Brehan. Guess he’d lined up some ladies for him during his trips to Addis.”

“So they found Brehan?”

“Yes, in northwestern Somalia. Apparently, our friend was running from his demons and trying to start over. So in exchange for amnesty and bodily protection, he gave Scotland Yard a detailed description of where he dropped us. And here we are.”